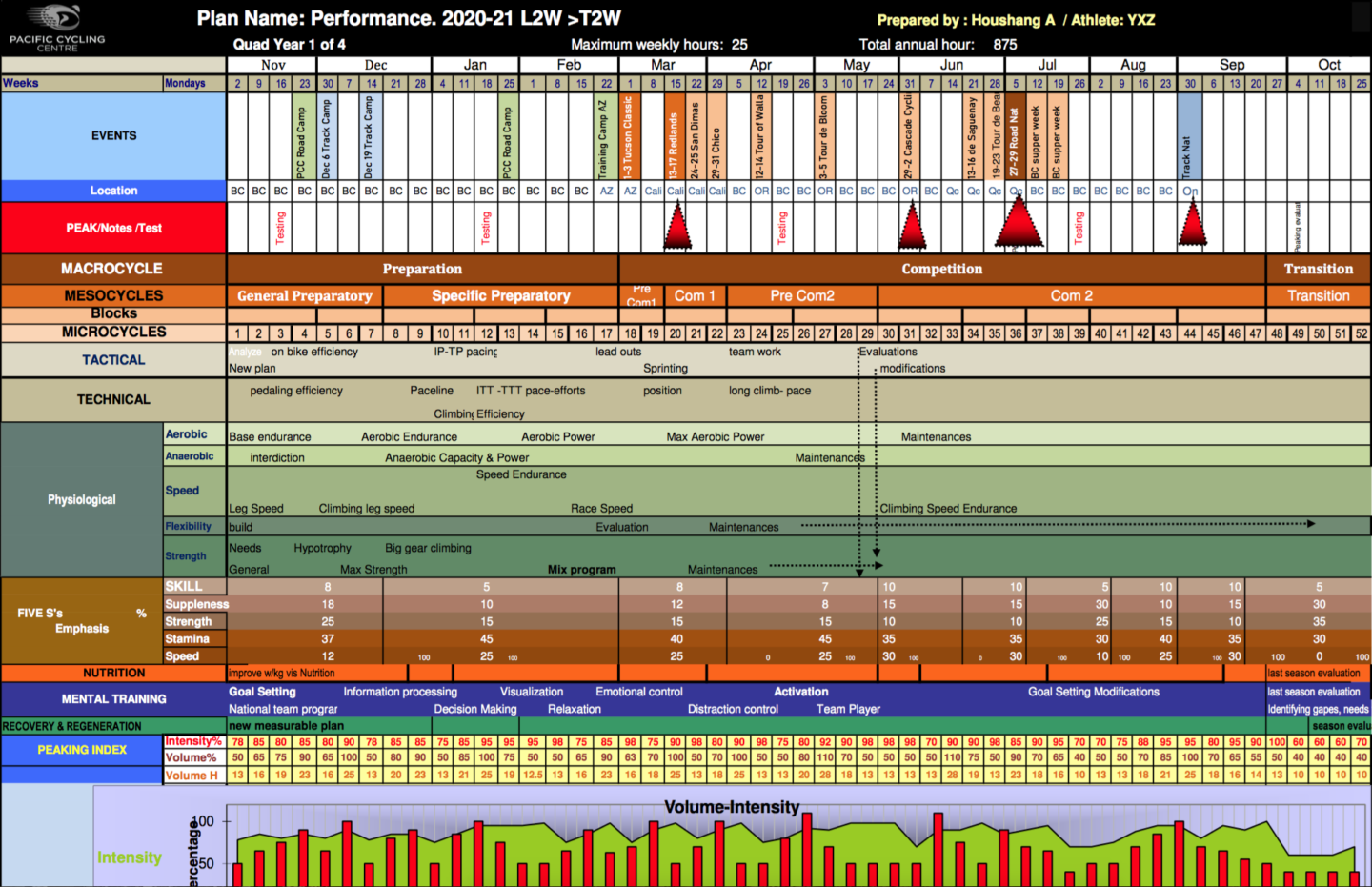

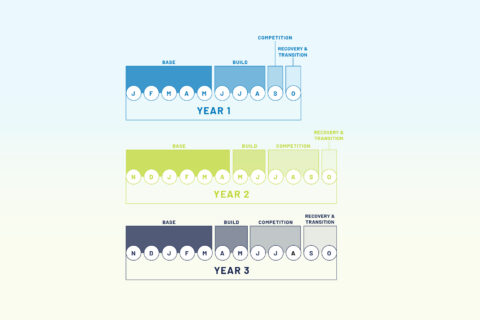

We review the art and science of developing and maintaining an annual training plan, which helps athletes progress and perform at their best.

We review the art and science of developing and maintaining an annual training plan, which helps athletes progress and perform at their best.