Once we understand the underlying mechanisms of motivation, we can more effectively harness or stoke it in our athletes before they end up derailed. In the case of the three high performing athletes we outlined in Understanding Motivation and How It Affects Performance (Peter Reid, Evie Richards, and an age-grouper identified solely as Tina), motivation began to work against them and threaten their goals. The sport they loved became toxic to them, their passion became obsessive and all-consuming. Now, we will explore how as coaches we can use this knowledge to better understand our athletes, and work with them to get the best out of different motivational approaches.

So how do we support athletes to reach their performance goals while maintaining the fine line between harmonious passion and obsession? How do we leverage the benefits of motivation without exposure to the detrimental side effects?

I will answer those questions by first taking you through a detailed account of the work that Tina and I did together to overcome the motivational challenges she faced. Then I’ll share my thoughts on what happened next for Reid and Richards.

It’s my hope that this topic illuminates the need for coaches to take a holistic approach to the work we do with our athletes. To truly understand our athletes, what motivates them and makes them tick, we need to look beyond the physiological, technical, and tactical details of coaching, the physiological silo that so often dominate approaches to coaching.

As an advocate of George Engel’s biopsychosocial approach to health and well-being, I see motivation as equally important to the athlete’s biology, skill, and execution. Engel suggested that to be healthy and able to perform well, we need to consider three overlapping elements: biology, psychology, and sociology.

Applying the biopsychosocial approach to coaching

As coaches, we are well-versed in the biology of the athlete—i.e., their physiological make-up, history, physical strengths, and limiters. It’s the other two elements of this approach that tend to garner less of our attention. The athlete’s psychological make-up also impacts performance—their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors which also encompasses beliefs, motivations, coping methods etc. Finally, the athlete’s social background—the economic, cultural, and systemic factors that might impact them, such as education, work, family circumstances, and social networks will also play out in pursuit of a goal.

Each of these three elements impact the others. For example, have you ever endured a tough meeting at work and then found it hard to raise the motivation to get out for a run? Chances are, you will feel better for doing it, but initially you are likely to feel drained and lethargic. This is a social situation that can impact both your biological and psychological experience. Recognition of the interplay between biology, psychology, and sociology is an important starting place for me when working with athletes.

Meet athletes where they are

My initial meeting with Tina was focused on starting the process of building trust. Cross-cultural research by social psychologist Susan Friske has shown that when meeting someone, particularly if it’s the first time, people want to know: 1) whether you care about them, and 2) whether you are competent at what you do. For a coach this means that you need to demonstrate careful listening, show empathy, ask open questions, and summarize important relational building blocks.

Our conversation was semi-structured and allowed to flow to create an informal open environment. We explored Tina’s observations of what was going well and current challenges in sport, work, and other life, as well as the possible consequences. We also broadly discussed Tina’s life and athletic history, her key relationships and support systems, and her health status.

“Nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care.”

Theodore Roosevelt

Gather data

In addition to the initial interview, Tina gave me access to her current training and work schedule, training groups, and the details of typical training equipment and venues. I asked her to complete a psychological demands profile, a questionnaire to assess her approaches against the psychological demands of her event (in this case Ironman triathlon) in terms of red, amber, and green.

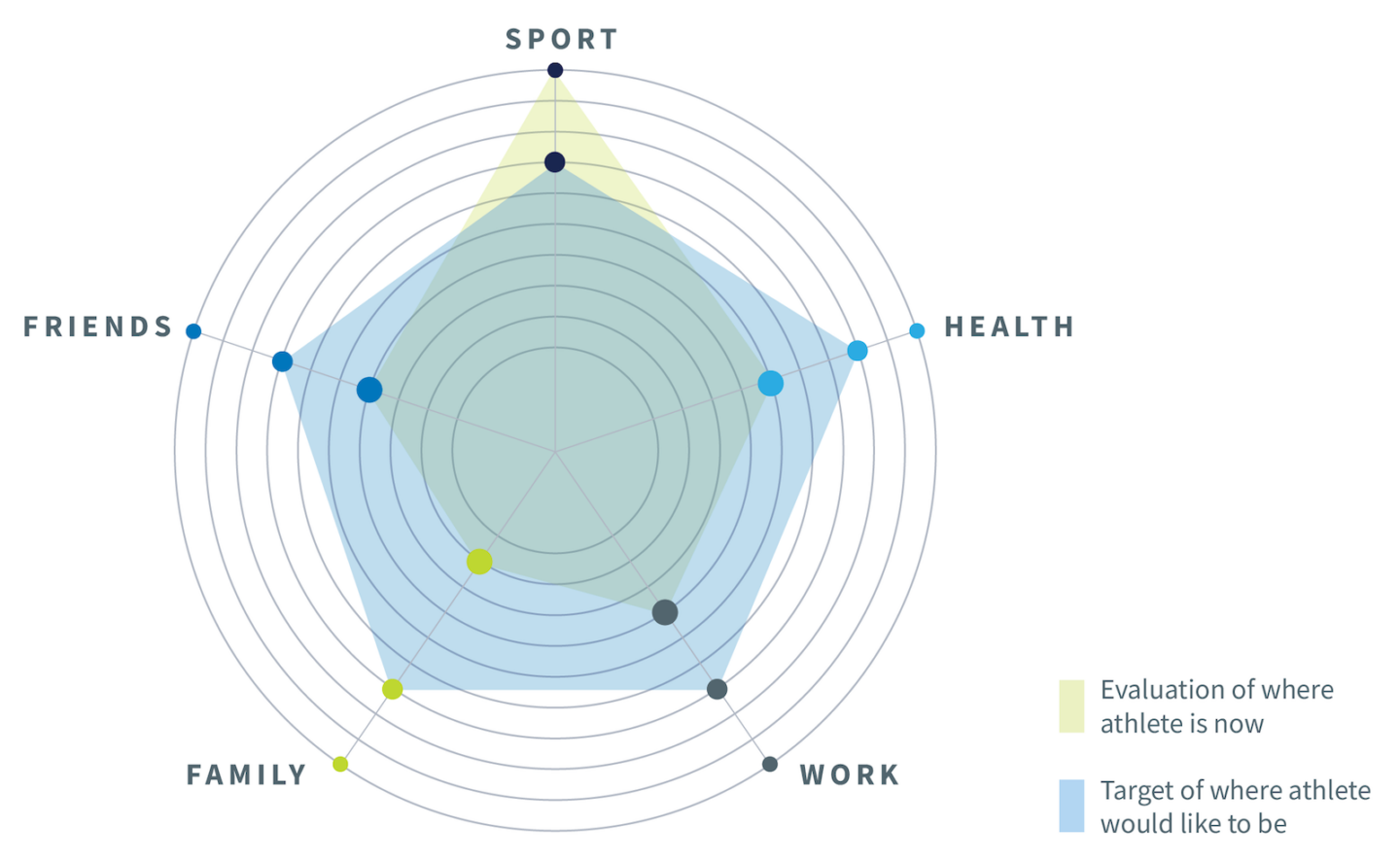

She also completed a simple self-reflection using a spider diagram profiling tool. This included the aspects of life that were most important to Tina: sport, work, family, friends, health. The profile provided a measure of balance.

It was clear that Tina was experiencing lots of negative emotions and consequences from developing an obsessive passion with triathlon. In her words: “I feel this continuous pressure to perform, and especially before big events, it can be overwhelming. I want to compete, but I want to enjoy it, not dread it.”

Tina’s self-esteem seemed contingent on her triathlon performances. If she didn’t perform up to her own high expectations, she felt pretty worthless. We noticed similar responses from Richards and Reid. Ricahrds’ focus on a less than stellar performance became about her weight and with Reid it became about training even harder.

Design a holistic training intervention

With Tina, the first step was to design a holistic package that would create positive, sustainable change. We agreed some foundation principles:

- My observations of Tina’s situation were based on two allied theories, the dualistic model of passion and self-determination theory. Therefore, any plan needed to be compatible with these approaches. This meant we needed a way to support Tina’s basic needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. The aim was to help Tina move away from the feelings and behaviors stemming from controlled motivation and toward more healthy and sustainable behaviors.

- Tina’s progression depended on her ability to be at the center of any decision-making, in order to maintain her autonomy. As coach I would guide and advise, but she would decide.

- We needed new goals, not just training and race performance targets, but process goals to encourage more of what she wanted: enjoyment, fun, and recovery. Developing mastery became our process goal, and we talked about how this would not be a linear journey but one that required perspective, continuous learning, and self-compassion.

- We also made a commitment to openness, honesty, and transparency. As part of our coach-athlete agreement we promised to be open to new ideas, to say the things that were on our minds, and be fully transparent about the reasons for our actions.

Use motivational interviewing to make an athlete-driven plan

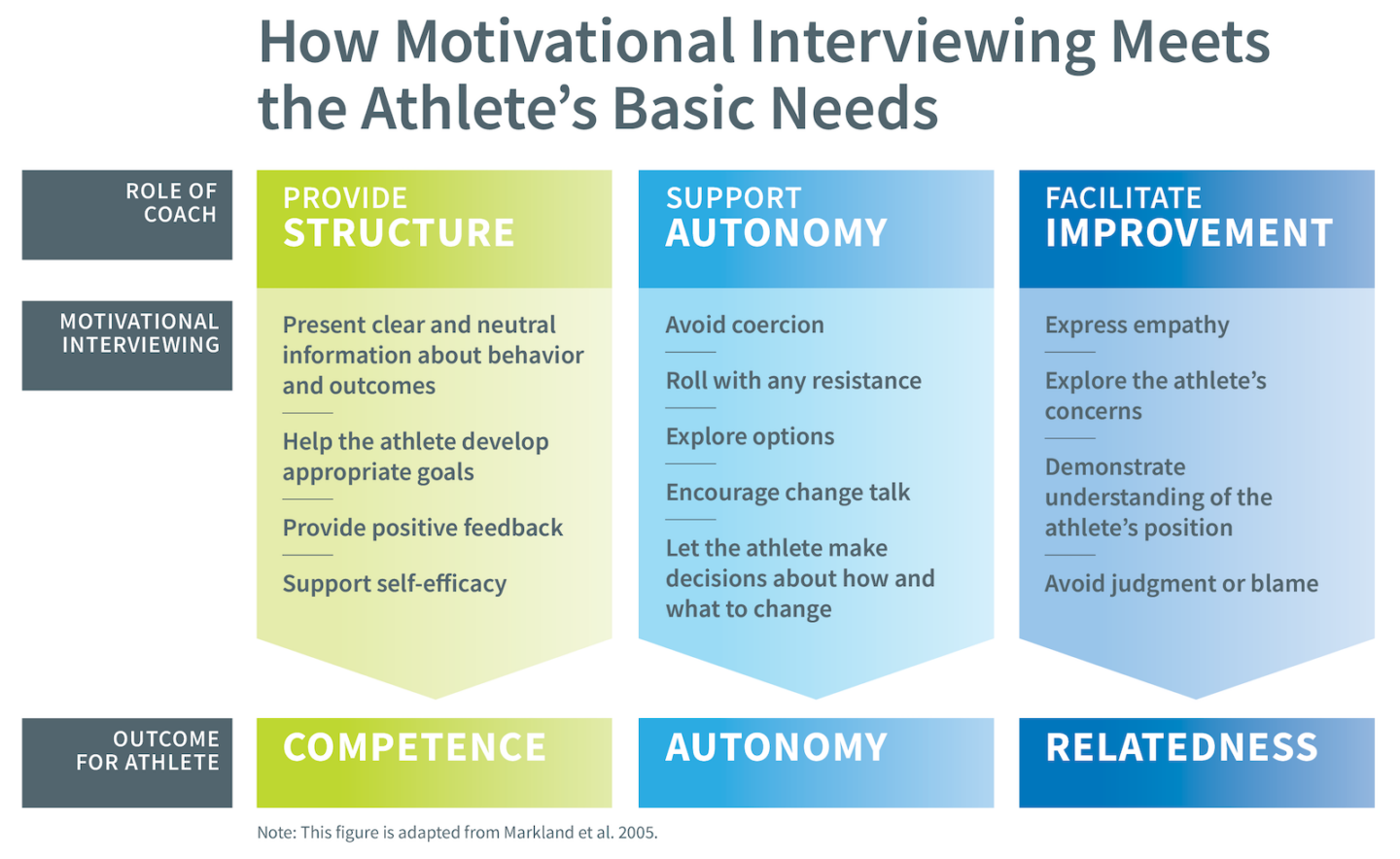

In addition to working with Tina to redesign her training plan and race schedule, I also agreed to weekly one-on-one conversations. I relied on a method called motivational interviewing in these interactions. Self-determination theory and motivational interviewing have been allied as complementary approaches in several research papers. Again, satisfaction of the athlete’s basic needs might explain the positive effects that motivational interviewing seems to generate with athletes (see table below).

In sport, motivational interviewing is an athlete-centered counseling approach designed to enhance motivation for a desired change. It uses mainly non-directive questioning styles to help resolve the athlete’s internal conflicts. With Tina this addressed such issues as her desire to train while at the same time feeling guilty that she was not spending time with family and friends.

In our conversations Tina would say things like: “I must make that swim session tonight, I can’t miss another one this month,” but her desire for a more harmonious passion was clear: “I feel guilty because I could meet with my sister tonight, it’s so long since we have met up.”

There are four general guidelines in motivational interviewing: expressions of empathy, development of discrepancy, rolling with resistance, and support for self-efficacy. I implemented these in an effort to gently guide Tina toward greater self-compassion and the changes she wanted to make.

Step 1: Build engagement with the athlete

The first step of the motivational interviewing process is to build engagement. I continued to take a collaborative approach with Tina by asking open questions, listening carefully to her answers without interruption, and reflecting on responses to her difficulties with empathetic phrases like “That seems like a tough situation” or “Ah, sounds like you might feel stuck?”

Using regular summaries preceded by phrases like “Let me see if I understand so far” or “Here’s what I have heard, tell me if I have missed anything?” further establishes engagement and supports the athlete’s need for relatedness.

Summaries are a great opportunity to promote “change talk,” or comments made by the athlete that point their willingness to change. These statements often arise in four categories:

- Problem recognition: Tina explained she had been struggling with the pressure she put on herself (introjected regulation) to perform in sport. She wanted to compete without anxiety about how much time she devoted to sport, however, she also worried she was not spending enough time with her family or friends.

- Concern: Tina worried that if she continued to compete at her current level and work with the same intensity, she might burn out.

- Intent to change: “I have some options, I’m just not sure which is going to lead to being less anxious or happier.”

- Optimism: “I must be able to find a way to make things work; others seem to manage it.”

Step 2: Focus the athlete’s direction

The goal here is to set and maintain the clarity of direction and create appropriate goals to support the achievement of another basic need: competence.

Tina had ideas about areas for focus, so we created an “agenda map” to get a broad picture of areas for discussion. These included career direction, training and racing, life roles, maintaining family, social life, and down time. Tina’s agenda map provided some structure, but it also maintained Tina’s autonomy to make decisions in each of these areas and prioritize their importance.

As a coach and motivational interviewing practitioner, I must be careful that my language maintains a supportive climate that acknowledges all three basic psychological needs. Phrases like “we might” and “you could” provide autonomy and support the development of options. Furthermore, I typically ask permission to add suggestions, rather than telling the athlete something more directly, which is likely to create barriers to change.

Step 3: Evoke further thinking around behavior change

This is where the coach further strengthens the athlete’s ideas for behavior change, identifying discrepancies and any cognitive dissonance. This meant allowing Tina time to consider and come to her own conclusions about her conflicting thoughts, further supporting her autonomy. For example, “Tina, you talked about being concerned about burning out. You’ve also spoken about the need to train three times a day during workdays. I am curious about how you reconcile these two things? What might smarter training look like?” This step led Tina to breakthroughs with some of her limiting beliefs.

Step 4: The athlete makes a plan for change

In this final step, I was looking for increased evidence of change talk and indications that Tina was ready and willing to make small commitments and actions. Tina initially proposed three change goals:

- Achieve better balance: Experiment with reducing the number of hours of weekly training. Tina’s mantra was “Train smart, not just hard.”

- Build confidence: Create a “confidence jar” to collect her notes on things that went well and things Tina was pleased with. When she felt low in confidence or self-critical, Tina planned to review these positive outcomes.

- Re-establish relationships: Make time to reconnect with important people in her life, starting with one family member and one friend. Tina wanted to be as intentional about her relationships as she was in her training.

Measure the athlete’s progress

At the six- and 12-week stages we revisited the spider diagram profiling tool that was used in our initial consultation to understand how Tina was progressing. Over time we made significant steps in reducing her performance anxiety, reducing her reliance on triathlon performance for self-esteem, and creating an environment that helped her enjoy a more sustainable life balance. This was evidenced by her changed approach:

- “It’s so nice to look forward to an event rather than to feel a sense of dread.”

- “I train hard, but I understand myself better now and it’s not the end of the world if I miss a session.”

- “I feel more in control now and I know more about what to do, if that starts to change.”

Tina and I continued to work with each other for several years and she tells me that she is still using some of the tools we worked on together to stay on track.

What of Peter Reid and Evie Richards?

A few months after walking off the run course at the Ironman World Championship and being out of competitive shape, Reid connected with Ironman coach and six-time world champion Mark Allen. Allen was an early adopter of a holistic approach to triathlon coaching, encouraging Reid to go back those intrinsic motivators that first got him excited to take part in the sport—the things that made him happy before the external pressures weighed so heavy. Reid rekindled his love for swim, bike, and run, and went on to win the world championship on another two occasions. Now he enjoys autonomy as he pilots flying boats in and around the islands off the coast of Canada.

Richards has gone from strength to strength, shifting to intrinsic motivation: “What changed for me was finally getting the right support and advice, from people who understood my body and my mindset,” she said. “About four years ago, I started working with my psychologist, and he brought back that kid in me who just wanted to ride their bike for fun.”

In working with a psychologist, Richards realized that cyclocross races were the only events where she was not sick beforehand. The nature of the event felt like riding her bike on the trails back at home when she was little.

She also began working with a nutritionist, which she credits for initiating some much-needed changes. “Now I know much more about my body, and by staying healthy you get the best out of yourself. Basically, I feel like a different person to those early days. I still train hard, but I also have a life and I am happy. I’ve got more chilled as I’ve got older because I have learned how to balance everything.”

In 2021 after finishing seventh at the Olympics, she won the 2021 Mountain Bike World Championship. Richards continues to ride as a professional but she is in a much better place to handle the challenges ahead.

Take the first step

If you recognize some of these motivational challenges within yourself or you coach athletes and notice similar things, go back to the basics. Ask: What are the intrinsic motivators that initially got me (or your athlete) into the sport—fun, learning, friends? Think about our three basic needs as humans—autonomy, competence, and relatedness. It’s likely that one or more of these needs are not being satisfied in some way. Identify any deficient needs and explore how those needs could be better addressed.

Interested in finding out more? Check out this article on motivational interviewing from Psychwire.

References

Brehm, J.W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. New York: Academic Press

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum. https://doi.org/10. 1007/978-1-4899-2271-7

Engel G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science (New York, N.Y.), 196(4286), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.847460

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

Mageau, G.A., Carpentier, J., Vallerand, R. J. (2011) The role of self-esteem contingencies in the distinction between obsessive and harmonious passion, European Journal of Social Psychology, Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. Published online 3 May in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com) http://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.798 41, 720–729

Markland, D., Ryan, R., Tobin, V. J., Rollnick, S., Motivational Interviewing and Self Determination Theory, Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology; Sep 2005; 24, 6; ProQuest pg. 811

Miller LS, Gramzow RH. A self-determination theory and motivational interviewing intervention to decrease racial/ethnic disparities in physical activity: rationale and design. BMC Public Health. 2016 Aug 11;16(1):768. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3413-2. PMID: 27515173; PMCID: PMC4982425.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change, 3rd Ed. New York: Guilford Press.

Patrick, H., Williams, G. C., (2012) Self Determination theory: its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/9/1/18.

Rollnick, S., Fader, J., Breckon, J., Moyers, T.B., (2020) Coaching Athletes to Be Their Best, Motivational Interviewing in Sports. New York: Guilford Press, ISBN 9781462541348.

Ryan, Richard M., Deci, Edward L. (2000) Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, Vol 55(1), p 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York: Guilford Publications.

Schellenberg, J.I., Bailis, D.S., Mosewich, A.D., (2016) You have passion, but do you have self-compassion? Harmonious passion, obsessive passion, and responses to passion-related failure, Personality and Individual Differences, Volume 99, 2016, Pages 278-285, ISSN 0191-8869, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.05.003.

Silva, M. N., Marques, M. M., & Teixeira, P. J. (2014). Testing theory in practice: The example of self-determination theory-based interventions. European Health Psychologist, 16(5), 171-180. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.708.6123&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Vallerand, R. J., Blanchard, C., Mageau, G. A., Koestner, R., Ratelle, C., Léonard, M., Gagné, M., & Marsolais, J. (2003). Les passions de l’âme: On obsessive and harmonious passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(4), 756–767. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.756.

Vansteenkiste, M., Sheldon, K. M., (2006) There’s nothing more practical than a good theory: Integrating motivational interviewing and self-determination theory, British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 63–82.