At its heart, polarized training is about something remarkably simple—how much low-intensity and how much high-intensity training should you do?

It’s a simple question, but it’s one that has generated a lot of debate. Some, including supporters of the polarized model, believe that we can only reach our potential by spending most of our time going easy, really easy. Others feel that the best training is done at a moderately-hard intensity—neither easy, nor hard. They support what’s called a “sweet spot” approach to training.

There’s another popular approach that many new endurance athletes mistakenly adopt, which adhere to the no pain, no gain mantra. They want to hurt every time they train. These supporters of high-intensity training believe that there’s no gains to be found from going easy.

Regardless of which camp you’re in, for decades coaches and physiologists have believed we need some blend of long, slow training paired with high-intensity work. The belief was these two different ends of the intensity spectrum train fundamentally different aspects of endurance fitness. Therefore, an athlete can’t be complete without doing both. It turns out that’s not quite true. In reality, both high-intensity training and low-intensity training ultimately activate the same pathway in the body, that is, they essentially produce the same results.

Getting the greatest gains

This begs the question, if the end result is the same, why not just do low-intensity or conversely high-intensity training all the time? Well, as with all things related to our bodies, it’s not quite that simple. While both high- and low-intensity training work through the same pathway in the body, if you only do high-intensity or only do low-intensity work, that pathway is never fully activated. Instead it plateaus. It’s the combination of high and low that seems to really get the pathway revving and this is what produces your best fitness gains.

So one of the most important training questions we can ask is not whether we should do high- or low-intensity training, but what’s the right mix of the two that will best activate the endurance pathway? This is the question that polarized training set out to explore. And by observing and studying how the best endurance athletes train, Dr. Seiler and other leading sport scientists found the answer.

Real world versus the lab

A top physiologist once told me that if you want to be a great physiologist, look at what the coaches and top athletes are doing, because they are always 15 years ahead of the science. This understanding guided Dr. Seiler’s work when he began analyzing the training data of the world’s top endurance athletes. He recognized that what the best athletes were doing worked. And more importantly, it was suggesting an approach that was quite different from what science was prescribing.

At the time, scientific research was heavily focused on intervals and specifically on the question of: What are the best intervals to produce the greatest gains? Whether exercise physiologists were aware of it or not, their research was promoting a high-intensity training model—suggesting athletes do as much high-intensity work as their bodies could tolerate.

Further complicating things, this research was heavily focused on interval work not because the high-intensity model was thought to be the best, but because of the very nature of laboratory studies. It’s much easier to get an athlete into the lab to do 20 minutes of hard work twice per week, than it is to have them do hours-long workouts every day for months at a time. Put simply, intervals were much easier to study.

What Dr. Seiler observed was that, contrary to the research, the top endurance athletes were not doing interval work all of the time. They were actually training slowly—really slowly—and doing a lot of volume. Nearly all of this work happened in what Dr. Seiler called physiological zone 1.

The physiological zones at the heart of polarized training

Every coach, expert, and national organization seems to have their own particular training zones. There isn’t even agreement on the number of zones, which can range from just three up to 10 or 11 zones.

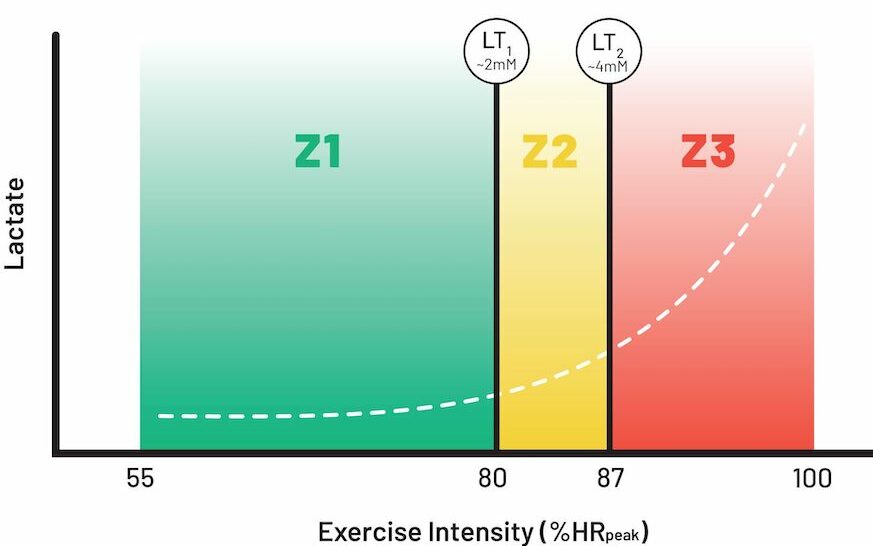

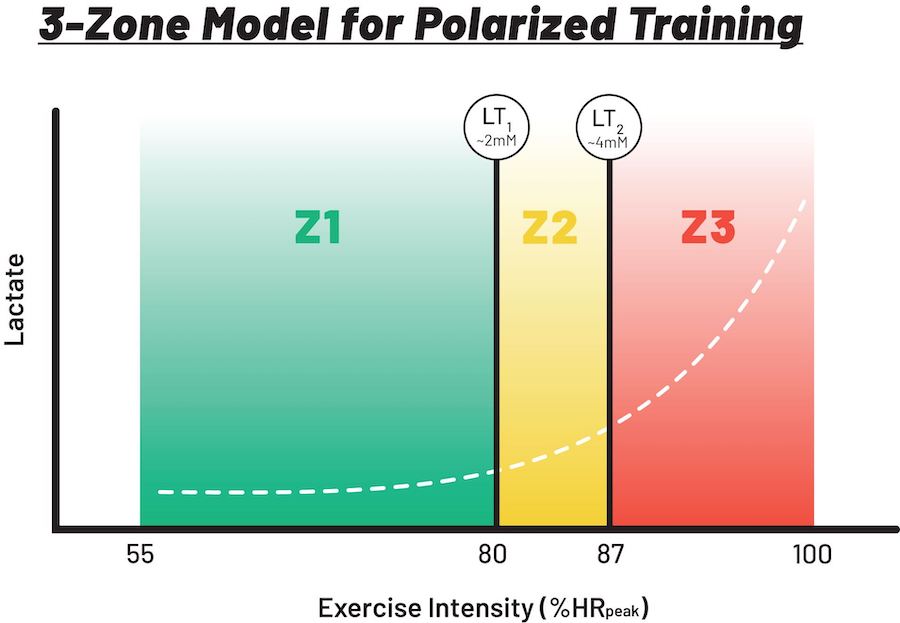

Fortunately, from a physiological perspective, there are only three zones and based on two measurable turning points or thresholds. The first is the anaerobic threshold. Most of us are familiar with this threshold. In fact, when a friend tells you they are doing “threshold work” this is generally the threshold or intensity level they are riding at. The anaerobic threshold is the pace or power that an athlete can hold for about an hour. Cyclists call it their FTP (Functional Threshold Power). Training at the anaerobic threshold is hard. The other threshold, the aerobic threshold, is much easier. It’s the intensity where the concentration of blood lactate starts to increase. Athletes can easily hold a conversation at this intensity and train at this level for hours.

These two thresholds define your physiological zones. Zone 1 is the intensity at or below your aerobic threshold. On the other end, zone 3 is any work at or above your anaerobic threshold. Zone 2 is any work done between the thresholds.

These three zones are essential to understanding the polarized training model because polarized training defines how much time an athlete should spend in each of the three zones.

The 80/20 principle of polarized training

Let’s return to the all-important question: What is the best mix of high- and low-intensity training? What Dr. Seiler observed in the top athletes was that they tended to do about 80 percent of their training time in zone 1, around 5–8 percent in zone 2, and 12–15 percent in zone 3.

To take it a step further, those percentages were based on the intention of each workout. When the training weeks for these top athletes were analyzed using a metric like power, they often spent as much as 90 percent of their time in zone 1.

While this mix surprised him, the real revelation was that less accomplished athletes were spending the majority of their time in zones 2 and 3.

This is the essence of polarized training—the vast majority of your time is spent in zone 1, a small amount in zone 3, and almost no time in zone 2. There are several reasons why this seems to be the ideal mix.

The real limits of zone 3 work

All of the literature on training reinforces the need to produce stress in order for the body to adapt. In other words, no pain, no gain. High-intensity training can produce a lot of beneficial stress. But this level of exertion also produces something called autonomic stress, which isn’t beneficial. This is the stress that prevents you from sleeping well after a hard session, raises your resting heart rate, and forces you to wait a few days before going hard again.

In his research, Dr. Seiler found that autonomic stress is like an on-off switch that is flipped just above the aerobic threshold—or zone 1. So, while zone 3 work is great for producing a big training stress, there is a real limit to how much you can tolerate.

Multiple studies have shown that doing two interval sessions per week produces better gains than one session. Three interval sessions per week produces no additional gains, but a lot more autonomic stress. Meanwhile, four or more high-intensity sessions per week can quickly push an athlete into an overtrained state. In other words, too much pain, no gains.

All of this means that you should be doing no more than two high-intensity interval sessions per week. In fact, to be true to the 80/20 rule, you might even want to consider doing two high-intensity sessions every 10 days. The rest of your training should be slow and easy.

The true value of zone 1 work

Let’s be honest—even a good long and slow zone 1 session isn’t going to produce nearly the beneficial training stress that you’d get from a zone 3 workout. However, a zone 1 workout also doesn’t produce autonomic stress. So, it’s possible to do a lot of zone 1 work without any fear of overtraining.

What’s particularly interesting is that while both zone 1 and zone 3 training activate the endurance pathway, they seem to activate it a little differently. Zone 3 work produces rapid gains, but those gains seem to plateau after about six to eight weeks. Zone 1 work acts much slower, but the gains don’t seem to reach a plateau. Over multiple years, this work can raise an athlete’s performance much higher.

So, if you have a key event coming up in six weeks, focus on the zone 3 work. But, if you’re trying to level up as an endurance athlete, you’re going to need to do a lot of zone 1 work.

The no man’s land of zone 2 work

There are many who feel that zone 2 work is the most beneficial training athletes can do. In fact, proponents of sweet spot training suggest that you place your focus on zone 2. And there are high-level athletes who have been successful with this approach—a good reminder that training is highly individual.

While the debate between sweet spot and polarized training will likely continue for a long time, the polarized model suggests very little zone 2 training is needed. And most top endurance athletes seem to avoid it. This is because zone 2 training doesn’t produce training stress that is as strong or beneficial as zone 3 work, but it still produces autonomic stress. In other words, as great as zone 2 training feels, it still comes at a cost.