We explore the ways in which the heart changes through training and adaptation with two leading experts in sports cardiology.

Episode Transcript

SPEAKERS

Jared Berg, Trevor Connor, Chris Case, Dr. Timothy Churchill, Julie Young, Dr. Bradley Petek, Ryan Kohler

Chris Case 00:00

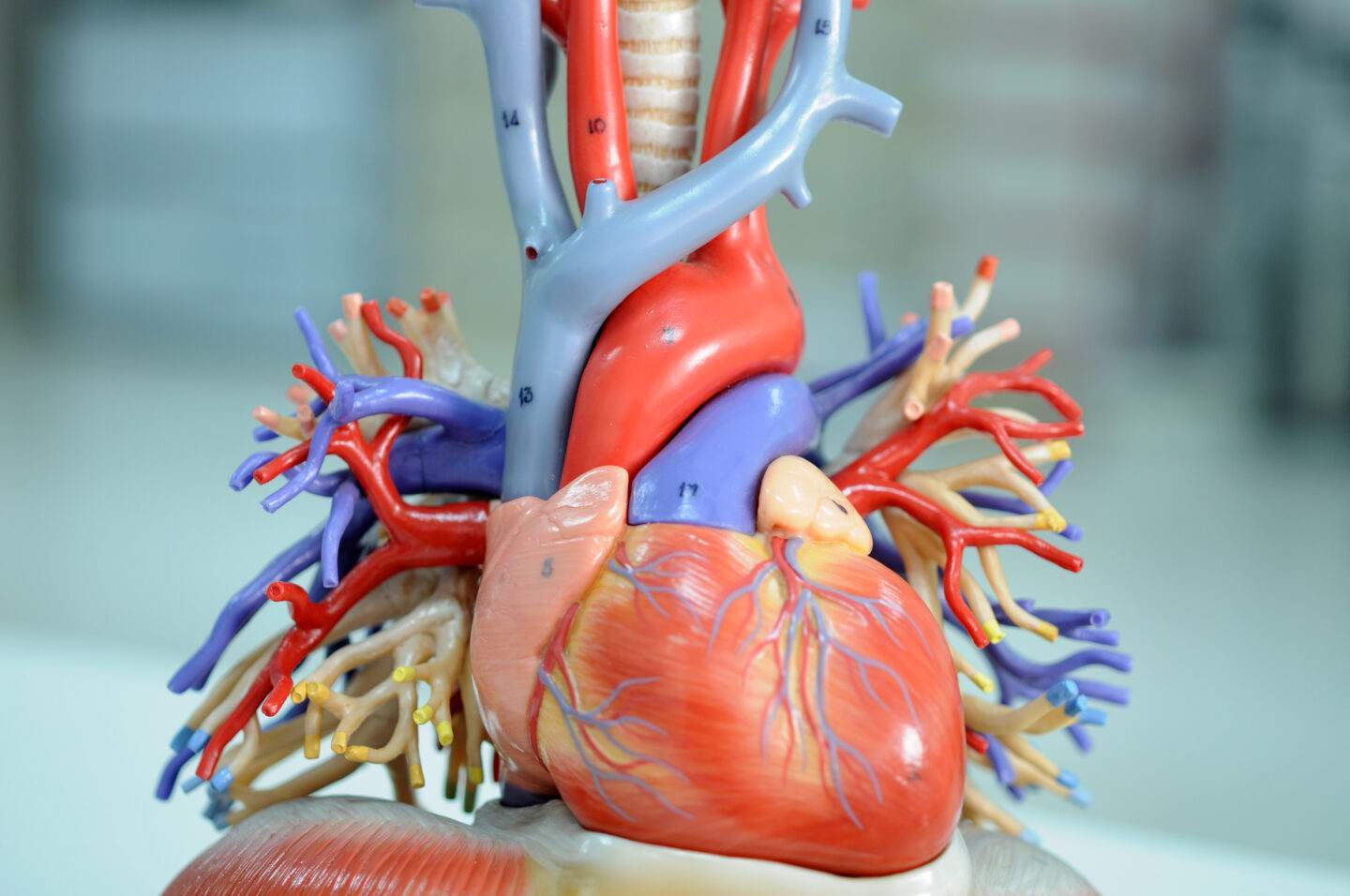

Hey everyone welcome to another episode of Fast Talk, your source for the science of endurance performance I’m Chris Case. On several previous episodes of Fast Talk, we’ve discussed the structural and biochemical changes that take place through the process of adaptation, through training. Today, we’re going to address one of the most important and interesting structural changes something called, exercise induced cardiac remodeling. As you train, your heart changes, this remodeling includes things like increases in chamber volume, and muscle wall hypertrophy. Of course, these changes don’t happen after one set of intervals. So today, we’ll discuss how long they take and how quickly they are lost if you detrain or stop training because of something like an injury. We’ll also explore both the performance changes and health consequences, if any of this remodeling. We’re excited to be joined today by two leading experts in this area of research and clinical practice, Dr. Bradley Petek and Dr. Timothy Churchill. Dr. Petek is a cardiology Fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital and one of the authors of the journal article entitled, “Cardiac effects of detraining in athletes: a narrative review,” that you’ll hear us refer to in the show. And Dr. Churchill is a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital as well and an instructor at Harvard Medical School. He is a member of that hospital’s cardiovascular performance program where he studies cardiovascular adaptations to exercise as they apply to health, disease and human performance, the perfect guest for this episode. We’ll also hear from coaches Julie Young and Jared Berg to get their understanding of how cardiac remodeling affects athletes of all abilities. Let’s make you fast.

Trevor Connor 02:05

It all sports nutrition is one of the most confusing and controversial topics. That’s because everyone has an opinion. And it’s hard to tell fact from fad. Plus what works for one person may not work for you. Now Fast Talk Laboratory’s is shedding some light on the science of sports nutrition. In our new sports nutrition pathway, we take a deep dive into the science of practice of sports nutrition to help you find what works for you. This pathway features experts like Dr. Asker Jeukendrup, Dr. Brian Carson, Dr. Tim Noakes, Dr. John Hawley, Julie Young and Ryan Kohler. They create a science based framework that will show you how to think about sports nutrition in a new way. Our sports nutrition pathway is the only guide you need to this complex topic. See more at fasttalklabs.com/pathways.

Chris Case 02:57

Welcome to Fast Talk today guys. Dr. Churchill. Dr. Petek, It’s a pleasure to have you on the show. We’ve been looking forward to this conversation about

cardiac remodeling

for a while now. Thank you.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 03:07

Thanks for having us, we’re excited to be here.

Dr. Bradley Petek 03:09

Thanks so much.

Trevor Connor 03:10

Yeah, it’s a real pleasure having you on the show. I’ve been reading some of your research and it’s it’s pretty exciting stuff, in my opinion.

Chris Case 03:17

I would assume they share that opinion.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 03:18

Yeah, no, we appreciate that it, obviously it takes up a big part of our life and we think it’s like we’re both in this area because we think it’s meaningful for a population that both that often gets kind of underserved by the medical establishment and, paradoxically, and so we both feel very strongly about work in this area. So we’re glad to hear that at least someone is reading it.

Trevor Connor 03:39

Oh no, I have quite enjoyed it. And Chris was, as you know, I mentioned this to you, Chris was on the authors of the the haywire heart, which was really trying to get at some of the the cardiac conditions that you see in endurance athletes, particularly A-fib.

Chris Case 03:54

Yeah I was much more about arrhythmias and some of the electrical problems you see. But I think as athletes continue to push themselves later into life in these generations that are doing so now, we’re starting to see a lot of things that we never did before. In some ways, I hope that that’s not a misstatement.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 04:14

That’s definitely a very true statement. And that, you know, I think the central message of our of what we do clinically is that exercise doesn’t prevent heart disease, it doesn’t make you immune. And so our job as as cardiologists in this area is to work with people try to come to understand who they are both as patients and as athletes and to try to work through all these particular things that are both that happened to everybody and also that are unique to the endurance athlete population.

Trevor Connor 04:39

So I actually want to start out with a little anecdote here, because you brought this up the need to get this out to the medical community when they’re dealing with athletes. And I remember very early on when I was writing for VeloNews I think my second article ever for VeloNews was about stroke volume, and how increase in stroke volume is one of the adaptations that you see in endurance athletes. And I had a reader write me actually a very angry email, saying that I basically made up the whole article, he said he was in his 80s, he talked with his cardiologist, show the cardiologist, the article. And his doctor said, there is zero research on that, told him it was all made up. That that is not one of the adaptations and particularly you don’t see that sort of adaptation in somebody his age. So he was quite angry with me and I wrote, I hope, a very nice email back, but include a Word document, right, with about 70 references about stroke volume adaptation, and highlighted one that said, I can’t remember the exact title, but it was pretty close to stroke volume is still a major adaptation in endurance athletes, even in their 80s, something along those lines. So highlighted that and he got the email sent me a very short note back saying thank you for doing that my cardiologist has some reading to do.

Chris Case 06:09

Very good. Well, should we dive in and let the experts tell us a little bit more about this, this idea of cardiac remodeling? What is it for the layperson? Let’s start there and then we can get into more complex science as we go through the conversation. I’m not sure which of you would like to speak first, but take your pick.

Dr. Bradley Petek 06:26

Absolutely, well I think our two goals here are to a not make listeners upset like that situation and be hopefully some of our research can shed light on some of these changes in athletes. So it’s more broadly known to the general public and people’s physicians about how best to take care of all athletes, and also those with heart disease. So cardiac remodeling. So cardiac remodeling is a process by which your heart adapts to different pressure and volume loads that are incurred with high stress situations like exercise. So as you can imagine, if you were to go out on a century bike ride, your heart is going to have to work a lot harder than your friend who is eating chips on his couch and over time, as your heart has to sustain high levels of fitness, it has to pump for high levels over long periods of time. In these situations, your heart will adapt over time and there are key structural and functional changes that it goes through to help you maximize your performance.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 07:31

I think that’s a great summary and I don’t have a lot to add there. I think this is something that has been observed and studied for going now on over a century. And this is something that we’re kind of progressively getting a better understanding of, and it’s the way I think of it as the heart’s adaptation to the sport’s specific training and hemodynamic. So that sort of the loads that are placed on the heart, and the way that it responds to those heart is a muscle, just like your biceps or your quads. And so if you work the muscle, it will grow, it will change and it will adapt.

Trevor Connor 08:02

So we’re gonna throw out a few terms here that we’ve we’ve never used on the show before. So get ready, we’re gonna nerd out a little bit. So we were just talking about exercise induced cardiac remodeling, or EICR. Now, there is a theory and I’ve been excited about getting to this because I wish I had this last name, this is a cool last name. But there is a theory about how this occurs and the fact that the remodeling appears to be different in strength sports versus endurance sports, and this hypothesis is the

Morganroth Hypothesis.

Chris Case 08:39

That’s not as exciting as I was expecting Trevor.

Trevor Connor 08:41

I did give a bit of build up, it’s still a cool name.

Chris Case 08:44

Okay. Sure.

Trevor Connor 08:46

So do you want to tell us a little bit about what the the theory or the belief is here? Yeah. Dr. Churchill,

Chris Case 08:52

Yeah Dr. Churchill, go for it.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 08:53

Yeah so Morganroth hypothesis comes from a 1975 paper by Morgan Roth, obviously, where he, he basically was the first person to pause it and put down on paper, the idea of the sports specificity to the training adaptation. And what that’s really getting at is that as your heart sees different types of forces acting upon it in the context of different sports, it’ll adapt in different ways. And so we often think about this and kind of paired dogmatic sports. So things like weightlifting, or alignment on a football team is a good example of someone, something which is a relatively pure really strength or purely kind of strength and burst activity. And the classification that we often use is dividing sports based on their static versus their dynamic components. So how much of it is an increase in the other sort of way to split the axes? How much of it is an increase in pressure? versus how much is is it an of an increase in the cardiac output or the amount of blood that your heart is pumping over time? And so on one end, you have the purely static sports and those are, as I said, things like weightlifting or the lineman in football. The other would be something like, like a marathoner or a cross country runner, which is a, we think of along the lines as a largely purely dynamic sport and of caveat that all these divisions are simplistic and life is not so clean, so cut and dry. And then there’s the sports which kind of combine the two. And I think that, for me, the best example of that is, is rowing is a really classic example of that, because in a rower and this has been studied, every stroke, obviously, there’s a huge endurance component. But at the same time, every stroke, at the catch every stroke at the beginning of every stroke, the competitive high enrollers, we’ll see a blood pressure that goes well north of 300 millimeters of mercury. So it’s the heart is exposed to both high pressures and as well as the high cardiac output stimuli. And so these different stimuli tend on the whole to give different adaptation. And that’s so the typical paradigm is in this in this transport, where we’re seeing the primary stimulus is high pressure facing the heart, the heart adapts like, again, like a weightlifter who’s doing bicep curls or something where the heart muscle thickens, and the heart muscle and then tends to actually grow on essentially sort of the chamber size on a relative basis grows inward, to reduce the wall stress, whereas by contrast, in the sports that have the high cardiac output stimuli, those in those cases, the heart cavity tends to get bigger. And then depending on the exact sport, sometimes the heart muscle will thicken. In conjunction with that, or in some cases, it will, the heart cavity will enlarge without muscle thickening. So that’s the sort of basic breakdown of the things that we see. And not always everything, you know, life is not quite so simple as a textbook. But that’s the the overall schema that we that we used to describe the two different sort of axes of that.

Trevor Connor 11:52

So I mean, the very, very short version is dramatically oversimplifying is in people in more strength sports, you’re going to see that thickening of the walls, but you’re not going to see an increase of the ventricle chamber size, where in endurance athletes, you’d expect to see that increase in the chamber size, but you wouldn’t always see a thickening of the walls. That’s that’s the very simplified version of the hypothesis.

Dr. Bradley Petek 12:18

That’s where it becomes important for specialized centers for heart doctors that also take care of athletes, because there’s a lot of borderline cases, and people who do sports that that change both of those that increase the wall thickness and increase the chamber size, or in people who are right on the borderline where other doctors may think they have actually a disease, but it’s just their exercise affecting their heart. So that’s why kind of taking a holistic approach to athletes as far as their clinical evaluation and research is so important.

Trevor Connor 12:47

Now, something I wanted to bring up. So I did a little preparation for this episode, and did read a very recent study called “aging athletes heart, and echocardiographic evaluation of competitive sprint versus endurance train masters athletes.” And they basically, in this study challenged the Morganroth hypothesis and said, they actually found quite different results that at least in these masters athletes, it was much more common in sprinters to see no cardiac remodeling. But they said in the endurance athletes, actually what they saw, the most common form of cardiac remodeling was actually a thickening of the walls.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 13:27

Yeah, that’s a great point. I think I think that gets to a couple things here, which are the first is that these as as I was saying before, life is more complicated than we painted these relatively simplistic descriptions. And there have been I’ll say, the preponderance of studies over the years has supported these sports specificity of these training changes. And I think one thing that we often look at when we look at this study design is oftentimes giving a little more weight or credence to studies that follow particular individuals over time, as opposed to I think I believe this, in this case, this was kind of a snapshot cross sectional one. So that’s one point. And I think the other the other important important point to take there is that all of these changes. And this is sort of one of the challenges of studying this in general, that all of these adaptations, all of these changes are really occurring in the context of everything else that’s going on in these people’s lives. So there’s, you know, these may be, we see this in where we have the 50 year old 60 year old marathoner, who’s still putting in 70 miles a week, but maybe also maybe has uncontrolled blood pressure at the same time, and so, if the all of these changes are occurring in the, in the context of any other any other medical issues that might may be happening, which obviously become more prevalent in the US when we look at older, older populations. So it does become a little bit of a more confounded study. I read that that paper with interest because I think it’s an interesting and there are there have been there are others over over time that could point to that also sort of challenge this Morgenroth hypothesis and challenge this, this sort of this dominant paradigm. But on the on the whole, I think this is this has been borne out by the majority of data and and when things don’t fit the bill, you know, it’s important for us to say, okay, we should step back, reevaluate things, does this change our overall picture? Is this kind of an exception to the rule? Or is it somewhere in between? I think, in my mind, this is something that is still hypothesis generating and that it’s not, it makes it very clear, this is not, this is not a law, there’s not F equals MA, this is not gravity. And these are complex biologic systems. So I think there are sort of potential confounding things that were at play in this particular article that you mentioned.

Dr. Bradley Petek 15:43

More importantly, we may need to recruit you to our team for bringing up studies that came out weeks ago, that’s really impressive.

Trevor Connor 15:50

Well, your study is actually listed as 2022. So it hasn’t even come out yet. It’s somehow I managed to read it. So yeah, I mean, it does look like there’s been a lot of research in this recently, because there was another one that I looked at also a 2021, which was cardiac remodeling induced by exercise and male masters athletes, they had a fairly large study size, and their results bore out much more in line with the hypothesis.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 16:16

Yeah, I think it’s again, it is a heterogeneous body of work. That, you know, these are all having done now, you know, some studies enrolling large collections of masters athletes in particular, that it’s hard to really sort of narrow in on on a very, very strict criteria to try to get the group as sort of similar along the important axes as possible. And so there there are, there is always going to be heterogeneity within groups and different, you know, a population in the US may have different genetic background, then populations in, in Europe, for instance, or in Africa. And, and I think there are undoubtedly kind of important, there’s an important interplay between the host, the person, the training, load, their genetics, and all the things which affect this is not to say that, without if you put, you know, we’re not allowed mice. So, you know, if you put two people on the treadmill, and make them do the exact same thing for 10 years, their hearts will probably look different. And that’s just that’s the interplay between their own personal physiology and they and their own genetics.

Trevor Connor 17:20

So we’ll get to potential health concerns in a minute. Before we get there, let’s just talk about athletes, particularly endurance athletes, who have no confounding issues. No cardiovascular issues, but they’re seeing some of these adaptations in their heart. What impact does that have both positive and negative?

Chris Case 17:45

And we’re trying to stick to performance now, but it’s going to be tricky to not talk about health when it comes to performance. Right?

Trevor Connor 17:51

Right, I mean, do these adaptations improve performance, or they just.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 17:56

So I think the easiest way to think about that is, there’s a couple things that are worth mentioning, I think the first thing is to focus on what you were getting at in terms of

stroke volume.

And I think the corollary is, is cardiac output. And so ultimately, cardiac output is your body’s ability to fuel the working muscle. And so the heart rate for a given individual, moreover, is, depending on their age, their maximal heart rate absent, there’s ways we can, we can give medicines that make it go down, but there’s not much we can do to make someone’s maximal heart rate go up. So cardiac output equals the heart rate times the stroke volume. And so the stroke volume, part of that equation is the is the variable one. So that’s, that’s the way to the stroke volume is the way that we can improve by increasing stroke volume, you can increase your cardiac output.

Trevor Connor 18:46

Before we dive into the impact on stroke volume with doctors, Petek and Churchill, let’s take a step back and quickly hear from physiologist Jared Berg, and his explanation what stroke volume is and why it’s important. Could you tell me what is stroke volume and cardiac output? And why is it so important to endurance athletes?

Jared Berg 19:06

Sure I certainly can. And so yeah, so stroke volume. Basically, it’s defining how much blood that we’re able to tip, how about with every heartbeat, and so few things can really go into that specific quality, I guess we will call that. But what we’re looking at is, you know, how much the ventricle of the Atrium can fill up with blood and how much that ventricle can can sort of like preload. And then when we’re going to pump out that blood is want to be able to have that ventricle filled with more blood so it could pump more blood throughout that body and get it to the muscle tissue in the arena where it’s needed. And so you know, stroke volume is basically simply defined as how much blood we can pump with every time we beat that heart and so If that heart can pump more blood doesn’t have to beat as much. So it’s basically more efficient at getting at getting oxygen through the body without having to work as hard as sort of that stroke principle.

Trevor Connor 20:11

No, I remember my early exercise physiology classes, stroke volume was listed as one of the most important adaptations for endurance athletes. Do you agree with that?

Jared Berg 20:21

I do agree, it’s certainly an important adaptation, but I think we need to take it with like, some people worry like, oh, yeah, my heart, my heart beats so much faster than my training buddies, right. And that’s, you know, simply a function of anatomy, people’s hearts will sort of, you know, build, and as we grow and mature and get into, you know, to adolescence into adulthood to a certain size, and it’s, you know, and ideally, it’s not going to, you know, it’s going to stay at a healthy, functional size for our specific anatomy. So somebody who has a little bit smaller heart is just simply going to be more off and like a higher cadence on a bike, versus someone who’s going to push the pedals a little bit harder, where someone with a smaller heart is just going to pump a little bit higher cadence, and that’s totally fine and totally healthy. All right, but as that person trains a little bit, and they really, you know, get up that high volume of training, and, you know, and works at all different, you know, trains at different capacities, you know, whether it’s slow endurance or, you know, threshold or via to max type work, all that is going to challenge the heart and unique ways and cause it to grow a little bit and increase the stroke volume. But each individual athlete will have sort of a limitation of how much their stroke wind will increase. And that is totally fine. And it’s that specific athletes best way of getting blood, oxygen rich blood to the rest of the body.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 21:53

So in that sense, the increases in the heart chamber size, we kind of focus on the left ventricle, because that’s what sends blood out to the rest of the heart. But this sort of plays out through the rest of the heart. So in increasing chamber size allows a greater stroke volume. And then this is getting into the physiology of this a little bit but allows a greater stroke volume at at the same pressure inside the heart as well, which is important because that’s sort of what people, if the pressures in the heart go up, that kind of can throw people off and make people feel poorly. So it allows a greater stroke volume. And that’s what gives you cardiac output. The other corollary part of that which is kind of a less commonly talked about, but vert part of the exercise induced remodeling. But I think an important part of the endurance athlete phenotype is the, the way the heart relaxes and receives the blood. So we call that the diastolic function of the heart. And so we commonly will see that we’ve some metrics, when we’re looking at people’s hearts to look at that. And we commonly will see Supra normal diastolic function, so a super normal ability to relax. And that makes if you think about that, through the same adaptive lens, that makes a lot of sense, because the heart, you know, so the heart can only pump out so much as it fills in, so to speak. And so the heart’s ability to pump out more requires the hearts ability to relax sufficiently in order to receive all the blood coming back to it. So that’s another kind of cardinal feature of the endurance athlete phenotypic adaptation that we will see and look for. And that certainly, I think both of those would function together as an adaptive partner in terms of supporting high levels of endurance activity.

Trevor Connor 23:33

So as I remember, you mentioned this in your review as well, that this cardiac remodeling doesn’t appear to affect function. But it definitely has that as you said, and that impact on performance that it’s going to increase the capacity of the heart to deliver oxygen to the the working muscles by as you’re saying, increasing that stroke volume.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 23:53

And when you say function there, I think you’re getting at the idea that things like the ejection fraction are?

Trevor Connor 23:59

so kind of the normal function of the heart. So if you’re sitting there on the couch, these

adaptations

aren’t going to hurt or help any sort of function there. But you would notice it in exercise.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 24:12

Yeah, I think that’s a fair statement. And sometimes we can actually see at rest, the same adaptation. So if someone has, if someone’s heart is adapted to training and has enlarged such that the stroke volume is increased, we can actually see that when they’re at rest, their heart doesn’t necessarily need to inject a high percentage of the blood in the heart. So that’s the most common metric that as a cardiologist will look at is what’s called the ejection fraction, which is what percentage of the blood inside the heart gets squeezed out every beat and so, again, intuitively, if you’re if your chamber size as your heart gets bigger, the amount of blood that it needs to eject on every beat in order to satisfy the beat the body’s sort of resting needs on a percentage basis. This can actually be lower. That’s something that that’s sort of an it’s an observation that we’ve seen in that it can be seen in endurance athlete and in particular, highly trained endurance athletes. And we actually, we showed this actually looking at a small group of professional runners. Over time, we actually showed that when carefully measured over time as they started their professional running careers, that the ejection fraction at rest, as their heart got bigger, ejection fraction went down incrementally and actually got to the can’t go into the range that would be that might be considered abnormal in many circumstance.

Trevor Connor 25:35

Is there a concern with that?

Dr. Timothy Churchill 25:36

Again, that gets to the importance of everything being kind of understood, and looked at in concert with each other. So in this case, the ejection fraction is looking appears low because the hearts adaptations are allowing it to, it’s, it’s still pumping, the amount of blood that the body needs, and sort of the resting state, it just happens that because the heart is bigger, the percentage that is pumping out is smaller, the challenges of metrics when when you look at a percentage metric, obviously, if you change the denominator, then you know, this, or chamber size, in this case, is the denominator. So that’s something that we think of is not an indicator of any pathology or any problems. It’s just a reflection of their hearts adapted state. And so that’s, that’s where, you know, when we when we look at these people, at people in this case, and trying to evaluate is this at rest, I wouldn’t call it a performance enhancement is just simply the way that your body, your heart adapts to your body’s needs at any given moment.

Chris Case 26:36

So Dr. Petek, if you wouldn’t mind, could you give us that brief synopsis of the changes that are actually seen?

Dr. Bradley Petek 26:43

Absolutely. So kind of overall is a 3000 foot view is that we see specific changes that happen in athletes to their heart over time, depending on what type of exercise you’re doing. So primarily strength or static exercises, like your weightlifters and your your alignment, in football, you generally see thicker hearts, and it’s generally an increased pressure load to the heart. In athletes, such as cyclists, who perform mostly endurance space exercise or dynamic exercise, we generally see that the hearts get bigger, and they dilate over time. And everything else in between just shows the importance of trying to study these different areas of these specific sports, and also take all of these findings, kind of in culmination. So we can treat each athlete as an individual and decide whether this would be normal or not for their body. And these specific adaptations allow people to perform at higher levels in their hearts to adapt over time.

Trevor Connor 27:50

So we’ve talked on the show before about the types of adaptations and how there are both structural changes and then there’s biochemical changes. I actually use stroke volume as an example, because there’s two ways to increase stroke volume one is what you just talked about, which is the remodeling of the heart. Another way to change stroke volume is to simply increase blood volume, which your body can do very quickly. So everything we’ve been talking about is structural changes. So I was really interested in hearing from you. How long do these adaptations take? Is this years to see this sort of changes in the heart? Or can they happen quicker than that?

Dr. Timothy Churchill 28:27

So it’s a great question. And the short answer is that changes can happen quickly, but can continue to be seen over time, sort of the best study model of this is looking at people over a one to three month timeframe. Certainly by in the three month time frame, we can see fairly significant changes in both increasing and wall thickness, increasing chamber size. We think a lot of that is thought to be mediated by the increase in plasma and plasma volume that can come certainly early in the in training process.

Chris Case 29:03

And you’re you’re seeing this in people who are untrained. And then they go on a regimen of some kind for one to three months. And they’re seeing these changes?

Dr. Timothy Churchill 29:10

Yeah, so you can see it and a whole wide range of people. So one of the sort of paradigmatic studies that has been done kind of by one of the folks that we work with has been looking at freshman athletes coming in nearby us at Harvard, and then looking at them as they undertake their fall training season their freshman year. That’s taking people who in most cases are actually pretty well trained, these are elite high school rowers who are joining the crew team or, you know, not necessarily at quite as elite but football players, etc. And so it’s taking people from a fairly high level of of training, but regardless, it’s still a substantial augmentation of the training volume and we pretty consistently see adaptation in these structural and functional changes. Measuring plasma volume is something that can be done, but it’s sort of technically more complicated endeavor so, that’s certainly an early change. When people look at the same individuals over longer term over the several year timeframe, we can certainly see further changes. I will admit most of the studies are not haven’t been on a sort of six every six months basis for years and years, it’s usually kind of a baseline, six months or three, three to six months, one year, and then three or four years, the exact tempo and the interceding time is a little hard to pin down. But there’s definitely a continued progression of changes.

Trevor Connor 30:33

I remember reading that and it was actually surprised that you can see some of that remodeling happened that quickly.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 30:39

And the same is true. I think, Chris, it asked about untrained people as well. And there are there are studies where we take people who sign up for to run a marathon under a charity fundraiser kind of thing. And it’s a good model where they they do a 12 week training program. And we look at them before and after and see the magnitude and the exact sort of specifics of what we see in their cases varies, but that the basic principle stands that we see both structural and functional, as well as overall other metabolic changes in that case as well and sort of across different populations.

Ryan Kohler 31:18

Hey, I’m Ryan Kohler, head coach and physiologist at fast talk laboratories.

Trevor Connor 31:22

And I’m Trevor Connor, CEO of fast talk labs between the two of us right and I have over 40 years of coaching and clinical experience. For juniors to masters national level athletes to club riders.

Ryan Kohler 31:34

Our team at fast doc laboratories is pleased to offer new solutions and services. Now you can get the same guidance and testing available to athletes at National Performance centers.

Trevor Connor 31:44

Wherever where you live or train our virtual Performance Center, be your support network, to get faster to get answers and to get more enjoyment from your sport.

Ryan Kohler 31:54

Schedule a free console, we’ll discuss your background and recommend a path forward

Trevor Connor 31:58

Book a coach and help session we’ll help you push your thinking to find new opportunities. We can troubleshoot challenges and find solutions. Even if you’re working with a coach, we can help support you and your coach. By bringing a neutral science based perspective to your training,

Ryan Kohler 32:13

Schedule inside testing you can do from anywhere in the world, we can reveal incredible insights into your personal physiology and strengths as an athlete plus next steps to improve your performance.

Trevor Connor 32:23

Prove your nutrition with a consultation tailored to your needs. Or create a personal race day nutrition plan.

Ryan Kohler 32:29

We even help you with workouts and skills we offer in person and virtual sessions to guide key workouts or improve technique. Fast Talk Laboratories is here for you, wherever you are, see how we can help it fasttalklabs.com/solutions.

Trevor Connor 32:48

So this then brings me to Dr. Petek, your recent review. And as I said the date on it is 2022 and we’re in 2021.

Chris Case 32:57

How did he do that?

Trevor Connor 32:59

I don’t know. You’ll you’ll have to explain that to us.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 33:02

He’s that good.

Chris Case 33:04

He’s that good. Very good. Nice. Glad to have you on the show.

Trevor Connor 33:07

And your review looked at, you know, obviously, there’s been a ton of research on producing these adaptations, but not as much on detraining. So you really dived into how quickly do these changes, does this cardiac remodeling, go back to normal after you start the training? And I will let you take it but I’ll start by also pointing out there is that that fairly well known study of Italian cyclists where they show it even after 13 years, you didn’t see them fully returned back to normal?

Dr. Bradley Petek 33:39

Absolutely. So I think you hit the nail on the head is there’s a huge disparity in the amount of research, there’s hundreds to 1000s of studies looking at what exercise does to the heart and this remodeling pattern that we see. But we took a look back and we said you know if an athlete gets injured, if they get sick, if they have a period of detraining, or if they have a period of rest after their season. What does this do to the heart? Do you lose it as fast as you gain it? And what were the results of these studies. So we were only able to find a few. It was in the teens, the amount of studies that we could find. And most of the data had been built actually previously on astronauts and about patients who were bed rest. And they found that if you were a normal healthy person coming into the hospital and you got put on bed rest, your heart could regress in size in a matter of weeks. So they found in about two weeks, your heart could thin your chamber size can go down and similar with astronauts who go to space. So the studies in athletes that have looked at this, the few that have looked is have found very similar findings to actually the astronauts and the patients who come in at bed rest which is fascinating. So you can find changes especially in the left side of the heart. You can find changes in the wall thickness and the chamber size of the hearts and In a period of about one to four weeks, so if you say, hey I’m going to go train for the Boston Marathon, and I’m going to train for, you know, a couple months, and then I’m gonna take a couple months off, you may have lost a significant amount of the cardiac adaptation and just a few weeks that you have gained.

Trevor Connor 35:17

Yeah that really shocked me when I read that in your study to be able to lose, see that sort of atrophy in just a few weeks? I would not have guessed that until I read your study.

Dr. Bradley Petek 35:27

Yeah, it’s fascinating. And it just shows that we all need to keep riding and keep as possible, right, we need to stay on the bike.

Trevor Connor 35:34

Well it makes me correct something because that’s something I talked to my athletes about. I have my athletes take a period off often have them cross train, but I tell them, a period of detraining in the offseason is important. And I unfortunately, I’ve always told them, you know, those structural changes, they’re going to stick around, you’re just gonna see loss in the biochemical and it sounds like I have been not quite accurate. Not quite correct.

Dr. Bradley Petek 36:01

And I think in your defense, I don’t think we really know too. So for athletes who cross train in the offseason, you probably get some effect to maintain your fitness by cross training as well. But the exact amount of exercise you should doing the exact amount of training to maintain the cardiac adaptation and the advantages you have are really unknown, because this area has really not been looked at before in a rigorous fashion.

Trevor Connor 36:26

Right. And so I think, my recommendation, it’s actually not too far off of what I have my athletes do anyway, thankfully. But based on your review, I think where my recommendations would go is you need that period. So if I’m trying to coaching a cyclist, I’m going to tell them, you need that, that offseason, I’d like to have you have a couple weeks where you get off the bike. But I still want you doing some sort of endurance sport, I still want you having that specific stimuli on the heart. So you don’t see this, this sort of detraining effect.

Dr. Bradley Petek 37:00

Absolutely. And that’s where it becomes really important to have people like yourself coaching athletes through this process as well, because you got to think about the other aspects to their musculoskeletal systems, their pulmonary systems, their psychological state. I mean, I think Dr. Churchill and myself are very focused on the little box in the center of your body, but the rest of it matters as well, too. So trying to figure out and individualize it for each athlete, but as much as you can rest other parts of your body, but stay as active as possible. And it becomes very important in the injury population too so if you you know, are a cyclist and you fall in you break your collarbone. And you know, you have to stay off the bike for a while, what can you do to maintain your fitness and maintain your exercise, and that may be able to help maintain your cardiac adaptations that you’ve worked for long to build.

Trevor Connor 37:52

I worked at Jared Berg for years as a head tester at CU sports medicine and Performance Center. He’s very familiar with

<h2>cardiac remodeling and athletes.</h2>

And when I asked him about it, he addressed some of the concerns that he’s seen. Let’s hear from him now.

Trevor Connor 38:07

I’m assuming as an exercise physiologist who has worked with a lot of athletes, you’re familiar with this whole concept of cardiac remodeling, where you see that increased size in the chamber of the left ventricle? Is that something that what the work you’ve done that you’ve seen it all? Is it something that you feel is important? What’s been your experience with it, or your understanding of it?

Jared Berg 38:28

I do feel that that’s very important, like an anatomical adaptation that needs to be considered and looked over and discuss with your doctor for sure. So you know, should we be doing regular checkup checkups and screens and everybody should, you know, I forgot we should have a good survey, EKG fingerprint. So they know how their how their heart looks. And in such an illness with the checkup and their physician, the idea that cardiac remodeling and that and that the ventricle walls can sort of thicken and become larger. Yeah, that that certainly can interfere with that natural communication of the heart, right, where we’re going to have, you know, chances for the ability for the heart to sort of get a little bit more out of rhythm, right with that thickening of those heart walls. So it’s certainly important to to monitor and make sure that your heart is you know, is beating at an appropriate rate. It’s not, we’re not getting like sort of premature ventricular contractions, you know, which can are sort of even like that. Even with atria, we get some atrial fibrillation with an athlete adapted heart. And so those kind of things can just sort of lead to sort of maybe dysfunctional stroke volume potentially, where we’re just not getting all that blood out of the heart with every beat and some of this sort of sort of sticking in a little bit of pockets in the atrium. Especially when with the atrial fibrillation, so yeah, so it’s sort of a napkin sort of, you know, when we don’t get that heart out of the all the blood out of the heart, we could have little, some potential for, I mean, basically blood clotting and out and something somebody’s been kind of concerned about. So lots of things to be worried about, or to be thinking about with the sort of heart remodeling. And you just need to make sure that we’re ever looking into it and that we’re, you know, seeing professionals, you know, your cardiologist and physician and such to make sure that our hearts still functioning is healthy and keeping us good shape and such.

Jared Berg 39:03

Yeah, so I was gonna ask you, when you start seeing these concerns in an athlete who you’re testing or working with, what do you do at that point, you just recommend they see a cardiologist or things that you could do as a physiologist?

Jared Berg 40:50

Yeah, they would see a cardiologist, and ideally, a cardiologist that works with some exercise physiology testing that we’ll be doing here on UKG testing, or you’re also doing the cardiac screening, right, the you know, or any imaging at that that particular cardiologist uses.

Chris Case 41:12

So we we’ve skirted around it so far, but it’s time to get into those health impacts of this remodeling. The research is saying that capex review is looking at how quickly some of these things take place. How quickly some of these things go away, if you will. Dr. Churchill, what health impacts does that have on a person?

Dr. Timothy Churchill 41:33

So this is obviously, you know, for at least for us, is the million dollar question in that this is an area where you see people coming in doing the sports they love, and with either established or concerns for heart disease. And so I think that the starting point here is to really emphasize sort of how difficult it actually is to really parse out the effects. So I think the things that we can say with certainty are, we know that exercise is good. Exercise is good for the body, good for health, good for the heart. And we know that this remodeling is associated with exercise. But trying to parse out kind of specifically, what does the remodeling part? And what are the exact implication of the remodeling part for health becomes a lot harder in terms of establishing causality versus just an association. I mentioned this earlier but the other key message, obviously being the exercise alone doesn’t make people and these adaptations don’t make people immune from heart disease, and that it can help but doesn’t necessarily overcome bad genetics. If blood pressure not controlled, a poor diet, other things like smoking, you know, any other thing like that. So that’s kind of the framework to start. And then it gets into the questions about how exercise, how EICR might relate to possible health effects. And I think for the most part, that’s an open book, I think the best established adverse health consequence of high volume endurance exercise is one that Chris wrote a lot about is in atrial fibrillation. And there’s a lot of theorizing about how the remodeling of the left atrium is likely an important part of the development of that condition. If you read a lot of papers in this, there’s a lot of diagrams for people theorize the pathophysiology of how this comes about. But there’s there’s very little actual kind of concrete science saying it’s one thing or the other. But I think that’s the area where the direct implications of remodeling for health might be somewhat more concrete. I think the other area that’s worth bringing up is the one I was mentioned before about the hearts ability to relax and to receive the blood. And because that’s one of the cardinal features, if we sort of step away from the athletes and look at patients with heart disease, and with some forms of congestive heart failure, one of the cardinal features that there is a stiff heart that doesn’t adapt, that doesn’t relax well and doesn’t receive the blood very well or very smoothly. And so it’s a very reasonable inference that the effect of exercise on the hearts ability to relax would likely make that type of developing the stiffer heart as you get older, and less likely, again, we know that’s an adverse health picture health phenotype. That’s a lot of conjecture. But I think that’s one that’s very plausible. And that’s been shown that if you take a group of older, previously sedentary people, and you train them for a year, you can make their hearts concretely less stiff. And we know that stiff hearts are generally not healthy hearts. So those are the areas that I would think that I would point two as the remodeling parts that have the most concrete implications for health. I think the parts about chamber size, are a little more harder to pin down. And as we’ve talked about, I think also the fact that they probably there’s probably a lot of undiagnosed coming and going of these over time, also makes it a little more complicated trying to get out what they might mean for health itself. So in a lot of ways, I think they may be a bystander in that exercise, as a manifestation of exercising all of its benefits for health. I think there are some concrete things as I was mentioning,

Trevor Connor 45:02

So something I wanted to ask you, because this was brought up in your review, I’ve read it a few other places is, if there is an association with future disease, what’s bringing it about? So I have heard this theory that if the chamber size, so the dilation of the ventricle or the atrium gets too big, and you don’t have a thickening of the wall, it becomes actually hard for the muscle to actually continue to pump that giant chamber. And that could lead to health issues. But in your review, you brought up the conduction system a lot and actually mentioned some studies where there were conduction issues in these athletes. And when they detrained and then retrained, they were able to essentially eliminate some of these issues.

Dr. Bradley Petek 45:48

Yeah I think that’s a really good point, you know, we are learning more and more as we go. But trying to figure out and watch what sport and watch heart conditions, it is okay to keep training and watch heart conditions, maybe you should stop for a little bit. And there was one example of a group of athletes that had extra heartbeats called pre ventricular contractions. And a small study show that if you detrained and took some time off, and you went back to training, you actually reduce the number of those. However, I think that the big thing to look at is how you feel, and what are the downstream implications. So you may decrease the number of those heartbeats, but what we really care about in the medical world, and I think what most athletes care about is this going to affect me long term? So is it going to be safe for my heart long term? And how do I feel? So I think really, in the future, that’s what we need to focus on is in which specific patient populations, would they benefit from taking a little time off? And in going back to training, in which populations? Is it okay for them to keep training and for them to keep doing what they love?

Trevor Connor 46:57

I won’t lie to you when I was in my late 30s. I wore my PVCs with a badge of pride as a as a high level cyclist now that I’m 50. I’m like, Yeah, that was stupid.

Chris Case 47:06

Yeah, yeah, the things we do. It sounds to me as if you both are saying there’s a lot of unknowns. And I think that that’s clear. But I was wondering if I could put you not on the spot. But ask for your recommendations. If you’re if you’re talking with a lifelong athlete, and he’s listening to this episode, and he’s maybe debating, aw man, are they saying that I should throw in these periods of detraining? Are they saying that detraining is bad? Do you have any recommendations as to what someone should do based on what we’ve talked about today in terms of remodeling?

Dr. Bradley Petek 47:41

Absolutely. So I think the main thing is we know that exercise is good for your body, the more people exercise and have regular exercise over longer periods of time, the better the health implications. But I think the real thing is listening to your body, when you’re exercising, as you’re going out, if you’re noticing that you’re feeling unwell, if you’re feeling new symptoms, there’s chest pressure, lightheadedness, that’s really when you should try to go to your doctor to get evaluated to see if something else is going on. But otherwise, I think the the important thing is just maintaining your fitness as long as you can. Because as soon as people stop moving is when they get into issues in the long term. So exercise is a great thing when used right and listen to your body and make sure that you’re you’re telling people if you are having any changes.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 48:27

And the one thing I’d add is I don’t think the understanding the literal training understanding that we have about the chain about the detraining effects on heart structure and function should be taken to suggest that people should never should not build in rest appropriate rest and or cross training into their training as Trevor was getting it and that I think both of those are essential. And we all in clinic, you know, every month or couple of months, we see someone coming in with a clear overtraining syndrome. So the the answer to the fact that detraining effects are seen on the heart is not to fear into overtraining, it’s to sort of be thoughtful about it to try to keep to pay attention to your body to work with a coach who sort of is attuned to what’s going on with you, and to try to balance things out over time. Because I don’t think the answer is just to say, okay, the answer is never to no rest days for the rest of your life. Because that’s also probably not the the the healthiest response there too.

Trevor Connor 49:29

I’m going to tell you though, that is I think one of the most fascinating things about the heart, all the other muscles in our body, they repair they adapt in arrested state. The heart never gets that luxury. I can’t go I’m going to stop beating for 10 hours and repair myself.

Dr. Bradley Petek 49:44

That’s incredible too. When we have patients who come in that have done you know, 100 Ironman races or 100 marathons it’s pretty incredible and they’ve never had a heart issue in their life, but their hearts been pumping that well and and maintaining such a high level of fitness. That’s kind of what both of us love and what has drawn us to this profession and wanting to help athletes.

Trevor Connor 50:05

It’s fascinating. It’s a really exciting thing to look at.

Trevor Connor 50:09

Doctors Petek and Churchill talked about the importance of seeing your doctor if you’re seeing strange signs because everyone is different. This was echoed in our conversation with coach and physiologist Julie Young, who has tested a lot of athletes and finds there’s no true normal.

Trevor Connor 50:24

Julie as a coach, how familiar are you with what’s called cardiac remodeling? In endurance athletes?

Julie Young 50:32

I mean, I know just from from reading the science just as as athletes, you know, our heart muscle remodels and gains strength and gains muscle mass.

Trevor Connor 50:44

So one other question here, because I know you’ve done a lot of physiological testing on an athlete, and I’m assuming you’ve done some testing on people who are not high level athlete. Do you feel that when you’re looking at test results, that the ranges, the expectations for saying they’re in normal ranges, they’re in healthy ranges are going to be different for an athlete population versus a more normal population?

Julie Young 51:11

When you’re saying that, like, what measurements are you thinking about? Like, are you thinking just heart rate measurements? Are you thinking lactate measurements? What are you thinking?

Trevor Connor 51:22

I would say a bit of everything, particularly the oxygen consumption, the sort of results you’d see on a metabolic cart?

Julie Young 51:29

Okay. Yeah, I mean, I guess one thing I’ve learned in testing is that there’s, there’s no normal, that there’s there’s such variability. And, you know, it kind of off topic, but just in terms of the metabolic testing, like, for sure, and in my experience, and opinion, there is no like, okay, you know, 65% of VO2 max, you’re burning fats, like, that’s something that I see, there’s just so much variability. And I also, you know, like heart rate, I think people have a misconception that they have this sort of heart rate means that and heart rate is so individual. And it’s, you know, it’s really that range. So I think that’s something that even when people see like 220 minus your age can be very misleading. And generally, I think most of those generic formulas are almost more detrimental than helpful.

Trevor Connor 52:22

So it’s almost instead of saying, here’s the normal range for an athlete, here’s a normal range for non athletic population, there’s just trying to have any sort of, quote, normal range can be a little counterproductive.

Julie Young 52:34

In my opinion, it is. And I just, I think it’s really misleading for individuals, at least those that have come into the lab, you know, and there, there may be concerned that they have this sort of heart rate, or their friend has that sort of heart rate. And, again, just I think, helping educate people on you know, the individuality of it, and the variability of it.

Trevor Connor 52:56

Okay, so I’m gonna actually take us on a tangent here. So I really enjoyed that conversation about the the heart and cardiac remodeling. But as I was looking at your research, I noticed that both of you have done a whole lot of research on the impact of COVID on athletes. So when an athlete gets COVID, how that impacts their training, any sort of long term effects, how they should address their training while they’re sick. It looked like really fascinating research. I’m sure we have least a few listeners who would be very interested in hearing about this.

Dr. Bradley Petek 53:29

Absolutely. So I think just as this whole pandemic has been a marathon for everyone, and we all hope that it comes to an end sometime soon, it’s also been a marathon on our end trying to figure out how we best protect athletes, and what’s safe to do, and to try and maintain fitness. So I think originally when the pandemic first began, there were reports out of Europe that were very concerning. There were reports that patients who are hospitalized with COVID-19 infection, that there was potentially a high percentage of patients who had inflammation around the heart called myocarditis. Traditionally, with athletes, we get really nervous whenever there’s any inflammation around the heart. It can happen from a variety of factors. It can happen from viruses, it can happen from other diseases, but in general, as us as cardiologists if an athlete were to have myocarditis, we generally recommend that they don’t train for three to six months, because there’s a risk that they could have a fatal heart arrhythmia. So they think we’ve been on a whirlwind down this roller coaster. Now because original data and hospitalized patients said there may be a high risk of myocarditis from COVID-19. So our real aim was to say, what is safe for athletes? Because we were seeing lots of different sporting organizations close their doors, we were seeing lots of different athletes completely stop training, and what can we do to best protect our athletes? So what we did as a group is we created a large consortium of primarily college based athletes and we had over 40 universities, over 3000 athletes. And we looked at athletes who were screened for having a cardiac condition. Most of these athletes got a heart tracing, they got a special blood test that shows if there’s damage to the heart called the troponin, and they either got an ultrasound of the heart called an echo, or something called a cardiac MRI, which can look for inflammation around the heart. They think reassuringly, now, from multiple different large scale publications in college athletes, professional athletes, and in other athletes subgroups, we’ve shown that the rate of abnormal changes on your cardiac MRI to suggest inflammation around the heart is very low after COVID-19 infection. So this made us all feel better that hopefully we didn’t need to screen every single athlete before exercise. And traditionally, what we had done is if athletes had symptoms suggestive of myocarditis, if they were having chest pain while exercising, and they were having new shortness of breath, and they had abnormal cardiac workup, like heart racing, then we would go down a pathway to check for it. However, in the pandemic, I was very nervous about our athletes. So they were testing almost everyone. And this comes back to the whole process just like this remodeling, where we were doing a lot of testing that has never really been done in baseline athletes doing these cardiac MRIs. And we don’t have a lot of good data to drive us. So it was really important for us to really figure out what’s going on to best protect athletes. But I think the punch lines for right now are that through multiple publications, we’ve shown that the rate of myocarditis is low in athletes, for athletes, there was also concerned about long COVID. And we also showed that the rates of persistent symptoms in athletes over long periods of time is also low after getting COVID 19 infection. And finally, the big thing is listening to your body. And one of the really concerning symptoms that we found was on athletes who have chest pain when they returned to exercise. So if you have the COVID 19 virus, and you you take a rest period for one or two weeks, and you have chest pain on return to exertion, that’s really the subgroup that should go to their doctor for extra testing, and make sure that they don’t have inflammation around their heart and talk with their own doctors. But overall, we’ve painted a pretty good picture that hopefully, the rates of this are low and athletes and people can continue to exercising. And once again, if you feel abnormal, make sure you reach out to your local physician.

Trevor Connor 57:36

Great, thank you.

Chris Case 57:38

Well, guys you’re both new to the program. But we always like to close out and episode with one final question, which is taking all that we’ve discussed here today, what is the most important

take home message for listeners?

Dr. Churchill? I’ll start with you.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 57:54

That’s a great question I think the important take home for is that the heart adapts the heart is a really amazing organ, which adapts to the stresses and the loads that your body placed upon it. And in general, I would say that adaptation can has implications for performance, but it’s not sort of, in and of itself, the goal or the the end, so to speak. This is an area of ongoing science. And I think the biggest thing is that I would stress to people is that this is an area where this is a specialty area within the field. And that if people if concerns come up, they should seek out to work with, in addition to their coach and their other other people to work out with a physician who’s attuned to these types of questions, these types of adaptations, these types of changes, and also to the to also to the priorities of someone who places a really high premium on the role of exercise in their life.

Chris Case 58:47

Great Dr. Petek, what would you add?

Dr. Bradley Petek 58:49

It sounds like you need to get a great coach. Somebody who also reads papers and is up to date on things and can really coach you throughout the process and work on you not only on your performance, your musculoskeletal health, but also listen to you and your concerns. When you think something’s abnormal, so you can make sure you get checked out. I think the biggest thing is continuing to support. I think Dr. Churchill and I are both biased, but continuing to support research in the sciences and specifically in athletes, which was traditionally an underrepresented population. Because just like the cardiac remodeling, we’ve come a long ways to figure out what’s normal for athletes and what’s healthy for athletes when people previously may have been restricted from the thing they love that could actually help them when their changes were absolutely normal. And in the setting of COVID-19 the same thing. A lot of athletes were restricted from doing what they love every day and I think merging data has reassured us to help safely return them back to sport and what they want to do and ultimately, that’s what’s going to affect their long term health and definitely psychological well being as I don’t think I could survive without running and cycling. So I know everyone else out there probably feels the same.

Chris Case 59:56

A couple of things I would add, it’s amazing, you know the stories that I started to hear once I knew a single person with a heart arrhythmia, and they came out of the woodwork, they were everywhere. So it seemed, that being said, I think they’re relatively rare. And I don’t want to scare people with this conversation in any way. I think that what we’re talking about are changes that are, quote, unquote, normal for the most part for the demands that people are placing their hearts under. So it’s not really something to be concerned about. Until it is in Dr. Petek mentioned, you know, the types of things you should be looking for that would be concerning and that you would want to see a physician about I think the other thing I learned, working with friends that have had heart arrhythmias is that I hate to say it, but not every physician really understands the athlete body. Trevor mentioned the 80 year old who was seeing his cardiologist who was like, ah that’s you know that’s not true. Is he saying that because of any other reason, then he doesn’t know the athlete body? I don’t know but in my experience, not every doctor understands what an athlete should look like, quote unquote, should look like or the symptoms they might feel or the things that they might see as symptoms that aren’t really symptoms, I guess you could say. So I would just make those two points. And then, Trevor, I’ll leave it with you to give us the final word.

Trevor Connor 1:01:23

I don’t think I’ve ever closed out before this kind of exciting.

Chris Case 1:01:26

You must have

Trevor Connor 1:01:27

No, I think this is my first. So we talk all the time on the show about training energy systems. And I have admitted that when we talk about energy systems, that’s real shorthand for all the different adaptations that happen. And I have received multiple times emails from listeners saying, Hey, can you quickly send me a summary of the energy systems you’re talking about? And what I kind of want to answer is, can I send you a textbook? But not a short answer? Yeah. And what I loved about today is we just talked about one of those adaptations, and you just listen to two Harvard, MDs who have studied this thoroughly say, man this is complicated. We don’t have all the answers. A lot of this is still up for debate. And it just for me, what I what I love about physiology is just, you can take any aspect of it and see how complex and amazing and robust it is. And you could spend a whole lifetime just studying that one thing.

Chris Case 1:02:29

Mm hmm. Very good. Thank you, Doctor Churchill. Thank you, Dr. Petek, for joining us today on fast talk, its been a pleasure.

Dr. Timothy Churchill 1:02:35

Thanks for having us. Really enjoyed it.

Dr. Bradley Petek 1:02:36

Thanks so much, guys.

Chris Case 1:02:38

That was another episode of fast talk. Subscribe to fast talk wherever you prefer to find your favorite podcast and be sure to leave us a rating and a review. The thoughts and opinions expressed on fast talk are those of the individual. As always, we’d love your feedback. Join the conversation at forums.fasttalklabs.com to discuss each and every episode. Become a member of fast talk laboratories at fasttalklabs.com/join and become a part of our education and coaching community. For Dr. Bradley Petek. Dr. Timothy Churchill, Julie Young, Jared Berg and Trevor Connor. I’m Chris case. Thanks for listening.