The offseason is the perfect time to assess our previous season, set goals and strategies for the coming season, and incorporate those into our training plans.

Episode Transcript

Chris Case 00:12

Hey everyone, welcome to Fast Talk your source for the science of cycling performance. I’m your host Chris Case.

Chris Case 00:19

The offseason can be one of the most productive times of the year; it offers the opportunity to reflect on last season, to assess what went well and what could be improved, and then to look forward and strategize about how to progress both in your training and in your performances. Today will focus on the art and science of how to set goals and incorporate them into your training. Coach Connor starts off with a discussion of how to determine your goals, first by performing a season assessment which feeds his gap analysis, which in turn yields a goal setting strategy.

Chris Case 00:53

Coach Ryan Kohler joins us for the second half of the show to describe his SMART analysis. That’s S for specific, M for measurable, A achievable, R realistic, and T for time bound, before explaining his method for incorporating that information into macro cycles, and then into mesocycles.

Chris Case 01:14

The offseason isn’t just about sitting back and relaxing, although you should do a bit of that too. This time of year is perfect for putting in some homework, being honest with yourself about where you’ve been, and where you want to go so that the coming season can be as successful as possible. And with that, let’s make you fast.

Chris Case 01:35

Hey, Fast Talk listeners! You may have heard about our new coaching education and community membership program Fast Talk Laboratories, we’re pleased to offer you a chance to become a Fast Talk Laboratories member for free! Our new Listener member level is free of charge and gets you access to over 130 Fast Talk episode transcripts. Our new episode transcripts are searchable, scannable, and include links to helpful resources that we mentioned on air. Listener members also get our weekly newsletter, which highlights new episodes and offers access to limited time free content on our site. So come join Fast Talk Labs. Just go to fasttalklabs.com, click “Become a member” and sign up as a Listener member free of charge.

Chris Case 02:17

Hello, everyone, and welcome to another episode of Fast Talk. I’m your host Chris Case, we’ve got coach Trevor Connor, Coach Ryan Kohler and today, we’re talking about goal setting. It’s one of the best times of the year, in my mind, I have many fond memories of sitting down, looking back, seeing what went right, what went wrong in that previous season. But also getting really excited, looking ahead and saying, Where can I be better? What events do I want to do to really take advantage of my strengths? What events do I want to do to test the things that I’ve worked on that may have been previously considered weaknesses, but I want to turn them into maybe new strengths or just bring them up a level. So it’s really in my mind a great time of year, there’s a lot of analysis that takes place. And you know, I remember sitting down with Joe Freels, book “Cyclist Training Bible” and just paging through that section and walking step by step through his process for looking back, looking forward – all of that. So today, we’re gonna dive into that goal setting topic, pick it apart a bit more. Let’s get into it.

Chris Case 03:34

Trevor, do you have any memories of sitting down with Joe Freels book maybe, or some other book, and getting into this process way back when? Maybe, in your case Trevor, 20 years ago?

Trevor Connor 03:47

I think I have the first edition of Joe Freel’s book and that was the very first cycling book I ever read.

Chris Case 03:52

Nice.

Trevor Connor 03:53

So I remember some of this. So if you remember, we interviewed him two years ago now for the newest edition of the “Cyclist Training Bible.” And I, over years as a coach, talk to a whole bunch of people about how to build goals, how to do season assessments, how to do gap analysis, and took all this advice and built what I thought was this really unique and really cool way of doing this. Then read Joe Freels newest edition of his book two years ago, and went, “Wow, this is virtually identical to what I do with my athletes.” Slightly different terminology, but it’s pretty much the same thing. So as much as I would love to say, “Hey, I came up with this all on my own.” Really, I have to give full credit here, probably all those people who are giving me advice had read his book. It was just filtering through to me in little bits and pieces and I just managed to put together what was already written.

Chris Case 04:51

Yeah, that said this is not a regurgitation of Joe Freels book here today. This is going to take in to the conversation we’ll bring in Ryan’s experience, Trevor’s experience, my experience of all of these things through the lens of a really well crafted method for goal setting and season planning.

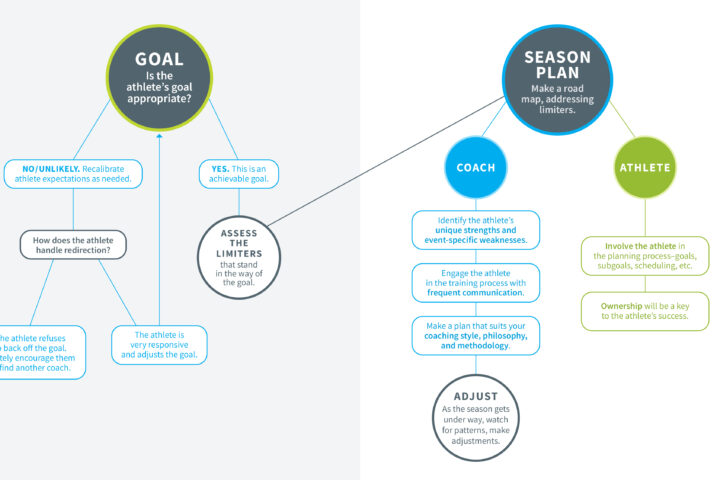

The goal setting process coach Trevor Connor and coach Ryan Kohler use with their athletes

Trevor Connor 05:12

So we are going to take you now through the whole process that Ryan and I use with our athletes. Chris asked me if I was prepared for this, I’m like “Chris, I have given this talk more times than I can count.” This is probably the episode I’m the most prepared for that we have ever done. So I will take you through how I get at defining goals with my athletes. There is a process to it, I think, just saying to somebody come up with goals without any background of how to define those goals, you tend to get either very unrealistic goals, or goals that they’re really not that committed to. Where the way I do it with my athletes, by the time they get to setting the goals or defining the goals, that’s actually the easiest part.

Chris Case 05:58

I feel like the one time we worked together on a project, and you were technically coaching me, you had me walk through this process. And if I’m not mistaken, this form, or the questionnaire, that you had me fill out, there was a back and forth. It was a process, it wasn’t just here, list a few things and “Okay, yeah, great. Now let’s move on.” It was “No, those are actually not really what I’m looking for. We want to change those a little bit. We want to nuance that sentence a little bit so that it really gets to a goal and not something else.” So we’re talking about a very specific thing here. And it’s a great point to say there’s challenge goals and then there’s unrealistic goals and there’s a distinction to be made there.

Trevor Connor 06:55

Something that was told to me very early in my cycling career is goals have to be realistic. That is really important. And when we get to the goals part, I’ll talk more about this. But your goal can be, I want to go the Olympics. But if you’re a cat 5 cyclists and you write down the goal, “I want to go to the Olympics”, that’s probably way down the road.

Chris Case 07:18

That can be a goal, but it might not be goal year one.

Trevor Connor 07:21

Right, it’s not something that really helps you right now. So you always have to think of what are goals that are ambitious, but achievable. And I always have my athletes define goals in a one year period of what is achievable this year – but ambitious. We’ll get to that.

Trevor Connor 07:40

So I have a three step process with my athletes and, I will tell you, there are times as a coach, and Ryan can probably speak to this too, where you really need to be a cheerleader. When I go through this process with my athletes, as you saw, I am as nitpicky as I can get.

Chris Case 07:58

This not the place where you’re a cheerleader.

Trevor Connor 08:01

Not at all. To the point that – so the second step is a gap analysis. I have a policy, I don’t care how good a job they do on the gap analysis, I send it back to them at least twice to redo it.

Chris Case 08:13

You are playing the role of a good editor here and making sure that someone is using the exact words they should be using.

Trevor Connor 08:21

And I have had many athletes be really frustrated. “I put so much work into that and you have all this red lines all over , you’re making me rework it.” That’s my policy. I don’t care how good a job you did, I’m sending it back to you. That was decided before you ever wrote it. Part of that is just that this is important, these are things that you really need to make sure you’ve thought through.

Step One: Season Assessment

Trevor Connor 08:46

So let me take you through the process that I have. So my first step is a season assessment. And actually this I got from Chrissy Redden.

Chris Case 08:57

And who is that?

Trevor Connor 08:58

Chrissy Redden is a Canadian Olympian. So she came and spoke at the center, talked to us about her success, and she talked about this sheets of paper that she had, that were her season assessment. So at the end of every year, she sat down and did this assessment and she said it was really the most valuable thing that she owned,

Chris Case 09:23

Looking back on what she had done or not done or accomplished or not accomplished in the previous season.

Trevor Connor 09:29

The point that she made is, yes, there are things that you learn every year, particularly in successful years, that at the time seem really obvious, it’s surprising how quickly you can forget these things. And if you don’t write them down, you finish a year and go “That’s obvious. I’ll never forget this,” – You do. You do forget it. And she said it is invaluable for her, whenever she’s struggling, she’s having a tough time, she would look back at the season assessments, read through them, and said invariably she would find something and go “Oh my god, how did I forget that?” Then she told us some great stories about other cyclists trying to steal these sheets from her and get all of her secrets, so she had to keep them kind of hidden and private. After I heard that I actually starting keeping a little book that travels to every race with me. So I have season assessments of the last 20 years. And that just goes everywhere with me. It’s the same thing. I look back and just go, “Oh my god, how did I forget that?”

Chris Case 10:35

And you actually write them down on paper? They’re not in digital format, Trevor?

Trevor Connor 10:39

This is the one place I actually do paper.

Chris Case 10:41

Wow. And a pencil or a pen?

Trevor Connor 10:44

Pen

Chris Case 10:44

Pen?

Trevor Connor 10:45

But I do have a pencil. I do own a pencil.

Chris Case 10:50

What if you lost these books, these notebooks?

Trevor Connor 10:53

I would cry, I would cry a lot.

Chris Case 10:57

What if those notebooks got into the wrong hands?

Trevor Connor 11:00

Chris, I don’t ever put them near you.

Chris Case 11:02

I don’t need your notebooks to beat you, son.

Trevor Connor 11:06

Oh, boy.

Chris Case 11:06

Yes!

Trevor Connor 11:07

So I keep other things in this book, it’s more than just my season assessment, but this is a little book that travels everywhere with me and –

Chris Case 11:15

I want to hear about the other things in these books

Trevor Connor 11:19

No double entries

Chris Case 11:20

Alright, we’ll save that for another episode people.

Trevor Connor 11:23

So season assessment. There’s a few parts to it. The first part is to look back at the whole year, and I don’t care if you’re a racer, if you’re not a racer, all of us have things that we want to do in the year, whether it’s just improved fitness, whatever, so this isn’t a “Only do this if you’re a racer.” I coach several athletes who don’t race and I have them do this as well.

Trevor Connor 11:46

So, step number one, look back on the season and ask yourself the question: Was the season a success? Yes or no? And you have to answer yes or no, there’s no qualifying, there’s no “well sort of” there’s no “maybe” – Was it a success, yes or no? Once you have answered that, then write a paragraph explaining why it was or was not a success. That’s important, because you just need to be realistic with yourself of was that a good year for me? Was that a bad year for me? You get into that school mindset and I’ve had athletes that worried that they’re going to get a failing grade. There’s no such a thing as a failing grade on this. I’ve had plenty of years that I look back on instantly wrote “no”. And here’s all the reasons why.

Chris Case 12:34

And that’s just as valuable, if not more valuable than saying yes.

Trevor Connor 12:38

Exactly. So that’s the first part.

What have you learned this year, that you never want to forget?

Trevor Connor 12:41

The second part, which is the most important part, is to pick the three to five things that you learned this year that you never want to forget. And what I have all my athletes do is write a title that they underline, that is the short summary of it, so something like I learned the value of making my easy rides really easy – something really short like that. Then I want two to four sentences expanding on it, explaining it. And again, there’s a reason for this; you might read this in five years, having completely forgotten this thing that you learned, and you need to be able to remember what that was about. So you need a quick description so you can look at it and go “Yep, no, I remember that.” Or you might read and go, “Whoa, I used to think that easy rides should be easy?” And then you read your description explaining why. So think of it as you are writing to yourself in five years who has forgotten this point. What do they need to know? So three to five things, most important things you learned this year.

What worked? What didn’t work?

Trevor Connor 13:50

And then the final bit is just quick and short, a list of things that really worked, and things that didn’t work. And this could be things like: I discovered eating this food made me have to get out of the race, so I will never eat this food again. Or I really liked this particular interval workout. Or I found riding with people really motivated me. Just little things like this, but just a list of what worked, what didn’t work.

Examples of season assessments

Chris Case 14:17

Now, can I put you on the spot a little bit here and say that we’re going to share some of these assessments, your assessments with people?

Trevor Connor 14:27

I have written all this up for my athletes. So let me bring up some of the examples that I gave them. So, the season assessment, one, so I have underlined, “The importance of going slow during base.” And then the description, “I found that keeping it slow really helped raise my stamina during the race season. What worked was being careful to watch my heart rate and stay fairly religious in the correct range.” So that was actually taken right out of one of my own assessments.

Trevor Connor 14:55

Same with this one. So I had underlined “I need a short taper: I find if I taper for more than a week I get rusty, the best taper for me is a hard week, then a few days rest then moderate training for three or four days before the race.” Now that’s me and that’s the whole point of the season assessment.

Chris Case 15:12

It’s specific to the individual.

Trevor Connor 15:14

I have had athletes where if I gave them that taper, it would destroy them for the race. That’s just the way I work. And that’s the value of this, it’s learning yourself.

Trevor Connor 15:24

I gave some of our examples already of what worked and what didn’t work, but here are some of the ones from my own book: drink mix you might really like, a type of interval you found didn’t work, a particular detail about your warm up routine, things like that.

Chris Case 15:36

Great.

Trevor Connor 15:37

That’s the first part: the season assessment and that’s really important. I encourage all my athletes, don’t throw this out, keep it. As a matter of fact, I used to give all my athletes their own little book, and tell them to do this and keep it in the book. So I highly recommend that and build this knowledge base, because you can go back over your own assessments. And like I said, you’ll be amazed what you have forgotten.

Chris Case 16:03

Maybe it’s a silly question: is there a particular reason why you do this with pen and paper, still, rather than just doing it in a cloud based document that lives online somewhere? Is there something about the act of writing this down? Or is it just a carryover, a habit, from yesteryear?

Trevor Connor 16:22

You know, I have thought about transferring it to my computer a bunch of times. It just started as a book and I really like it as a book. And that book always goes to races with me. And I like the night before important races to just go through the book. There’s certain pages that helped get me in the right mindset that remind me of things. I have some pages in there on what works and doesn’t work for me and racing. And it just really helps me to sit there on my bed, getting ready for the next day, to just read through all this.

Chris Case 16:56

Yeah, so you watch Rocky, then you watch Chariots of Fire, and then you go through your book while you’re pinning your number on your jersey and you’re set.

Trevor Connor 17:05

Right. Then I go find somebody, beat the crap out of them, and go to bed.

Chris Case 17:10

Wow, what a pre race ritual. That’s great. Entertaining, violent, and educational.

Trevor Connor 17:15

While from what you’re bringing up, I’m like, “I’m going to be revved up if I”m doing all that. I have to go work it out of my system.”

Chris Case 17:24

All right.

Trevor Connor 17:25

So that is part of my routine. And I just like it as a book, not the night before a race flipping through a computer. It always has concerned me that if that book ever burned up, I would cry a lot.

Trevor Connor 17:39

I will also say going back through the years, part of the reason I find it really valuable to say was the season a success or not, I have found it interesting when I go back to really old season assessments, like 10 years ago, where I’ve pretty much forgotten everything, you see the difference in tone. If it was a successful year, you can really see, my writing is much more positive, I really focused on the things that worked. It was an unsuccessful year, I can see the difference in my tone, a little more defeated, a little more objective, a little more focused on the things that didn’t work.

Chris Case 18:13

Yeah, this is not unlike the notes that people put in training peaks for given rides. There’s a bit of psychology in the positivity or negativity to the tone that they’re using, right? And this is just on a grander scale for a season.

Trevor Connor 18:28

Exactly. But I’ve actually found it really interesting that at times when I am struggling, and I noticed that I’m getting negative about my own training and my own season, going back and reading those seasons assessments from really good years, reminds me of the mindset and actually helps to change the way that I am thinking about my current season. So this kind of a Gestalt thing here, which is the hole is bigger than the sum of the parts, sometimes you get something out of reading that season assessment, that’s more than just the little tips and tricks that you learned.

Step Two: Gap Analysis

Chris Case 19:04

Mm hmm. Great. All right, step two?

Trevor Connor 19:10

Step two is the gap analysis. This is, to me, the most important part. And this is where I will have athletes go through it again and again and again until they want to shoot me. But I think it’s really important to go through the process and to rethink it a few times. So, a gap analysis means you are doing an assessment of where you’re at, where you are trying to get to, and what is separating you, why you are not already there. This is where people struggle the most, my athletes struggle the most, because they immediately want to jump into goal setting. So here’s one of the strange things, and look, I’ve taken business school classes, I’ve taken sports psychology classes, and they always tell you “Don’t focus on problems, focus on the solutions.” And we’ve all had that ingrained in our heads. So right now, I’m going to tell you, if you want to do a successful gap analysis, focus on the problems. Don’t think about the solutions yet.

Trevor Connor 20:13

And I will give you an example of why. This was something that I learned with one of the first athletes I’ve ever coached. I had him do his gap analysis and instead of saying, “One of my gaps is when I’m in a race and it starts getting really intense, I can’t respond to the big attacks.” That would be a good gap. What he wrote was, “I need to work on my one-two minute power.”

Chris Case 20:42

Sure, he tried to identify the solution before even realizing what the true gap might have been.

Trevor Connor 20:48

And being a fairly new and experienced coach, I went, “Okay, cool lets work on your one-two minute power.” And he was doing intervals where he’s putting out amazing power. So I’m like, I don’t get why this is an issue. So fortunately, then he started racing. So I was working on this with him through the winter, getting him ready for the race season, so he started going to his first races and lo and behold, you saw what the real issue was, which was, the tax wouldn’t start until a couple hours into a race, so the field would be gone fairly steady. And he was about two beats per minute below his threshold heart rate for those two hours before the attacks happened. Where all those guys who were attacking, we’re probably at a 130 – 140 heart rate, not struggling all that much. He didn’t have the fitness.

Chris Case 21:37

Yep. So when he got to that crucial point in the race, he didn’t have as much left. So it wasn’t at all about one-to-two minute power, it was about something very different.

Trevor Connor 21:48

If you are going easy, you always have a big attack – even if you say my attack isn’t my great strength. I’ve always said I’m not a sprinter, I don’t have a good one minute, but if I’m riding at 130 beats per minute, yeah, I can put out, for me, a pretty damn good one minute.If you were already at your limit, I don’t care what sort of one minute power you can do fresh, you’re not gonna be able to tap into that.

Trevor Connor 22:14

So that was a big lesson for me. And so that’s why it’s important in a gap analysis – don’t identify the solutions, because until you understand what the problem is, you might actually be identifying a solution, that is not the solution to the problem. So you got to identify the problem. And that’s the gap analysis.

Trevor Connor 22:38

And I guarantee you, everybody, your first attempt at this, you’re gonna go, yep, I got that you’re gonna write it, I’m gonna challenge you to reread it and remember what we just talked about identify the problem, not the solution, and you’re gonna be surprised how much you actually still wrote solutions. I have athletes who I’ve worked with for five, six years, I have this talk with them every year and the first pass of the gap analysis of all solutions. Then I go, Great, go back and identify the problem.”

What is your current level

Trevor Connor 23:05

So let’s go through the steps for the gap analysis. The first part is to identify your current level. This is where you really need to be honest with yourself.

Chris Case 23:17

And what do you mean by your current level? What terminology would people put on that?

Trevor Connor 23:22

So that depends on the rider. If you are a racer, you need to define yourself relative to the field that you race. So an example would be, I am a top 20 Regional cat four rider. If you’re not a racer, then you need to come up with ways of defining yourself that are related to how you want to see yourself, even though we haven’t gotten to the goals yet, related to your goals.

Chris Case 23:48

So in the context of the type of performance you’re looking for, whether it’s a granfondo, or a gravel race or something.

Trevor Connor 23:56

So if you’re doing a grand fondo, where would you define your level currently in a grand fondo? If you just go riding with your local buddies – so for example, I have an athlete I coach who doesn’t race, but he goes out and rides with his brother all the time. And the fact of the matter is, he’s very competitive with his brother. So he defined himself as, “I struggled to hold on to my brother’s wheel.” That was his current level. So if you’re just focused on fitness, put in those terms. If you’re just trying to get healthier, put your current level in terms of where your health is at. But you have to be honest.

Chris Case 24:32

Right. This whole process takes a lot of honesty.

Trevor Connor 24:36

And it’s tough. And again, you’re not being graded on this.

Chris Case 24:40

Yeah, I mean, the ultimate – if you’re not honest here, then the chances of you improving are less. If you are really honest here, the chances of you getting to where you want to be are that much greater, would you would you agree with that?

Trevor Connor 24:53

Yes. Good point. Thanks for the reminder. There’s actually an analogy that I use with my athletes that I think really helps to describe this. So I use a map analogy when I’m trying to describe this gap analysis, it’s: you’re trying to get somewhere. And we talked at the beginning of this episode about how you might be trying to get to the Olympics. But you have to think about where you are right now, and what are the steps. So this is the same thing. You might be trying to get to Miami. That might be the ultimate goal. To get to Miami, you have to first know where you are. And that sounds like a really stupid thing to say, but the fact of the matter is, if you are in Seattle, which kind of sucks because that’s a really long drive to Miami, but if you are in Seattle, and you think you’re in Atlanta, you’re gonna get really lost. So might be nice to say you’re in Atlanta, much shorter drive, but you’re not going to get there. So start by first saying, “Where am I at? Okay, I’m in Seattle. Got a bit of a drive ahead of me.” But knowing where you are, you can then say, “What is the next step? What is the next location to get to?” So, – I’m trying to think of my geography right now but – maybe the first step is to get somewhere in Montana. So think of that as that year’s goal? What is accomplishable this year? Okay, so the next step for me is to get to Montana, once I’m somewhere in Montana, then I’m going to try to get somewhere in Idaho and it’s taking these steps to ultimately get to Miami.

Trevor Connor 26:36

So that analogy is basically the way this gap analysis works. It’s first start with where am I at, you got to be honest, if you’re not honest, you’re going to get lost. Then what is the next step, the next level? So in this analogy, what’s the next place that you can accomplish? So when I talk with cyclists, I say in a year, but in the driving analogy, maybe it’s what’s the first place that I can get to before I have to stop for the night? Then the next day you assess where you’re at, what’s the next place that I can drive to that I can get to before I have to go to bed? So gap analysis, same thing, where am I at? What’s the next step? Then the next year you do your next gap analysis, where am I at? What’s the next stop? It’s got to be achievable and it’s got to be realistic.

Chris Case 27:30

A to B, B to C, C to D instead of A to X.

Trevor Connor 27:35

And you are never going to get to the next stop if you don’t first recognize where you are. And it’s tough. Often you’re going to do the gap analysis, look at where you are and go, I don’t like this. But accept it because if you accept it, you have a better chance to get into that next place. So that’s the first part. Where are you at? Make it one sentence, succinct, to the point, be honest.

Chris Case 28:00

What would your sentence be right now, Trevor?

Chris Case 28:04

My current level?

Trevor Connor 28:05

Yeah.

Trevor Connor 28:05

So I’m still racing. I’m still racing in the one twos so I would say, “Able to hang in the field, but not a contender when the race gets hard.” Which is really hard for me to say, but that’s the truth. Gap analysis, you’re always trying to say – so the next part that we’re going to talk about is the next level – you’re always trying to see where can you improve. I don’t ever write a gap analysis saying here’s where I’m at and by the end of this year, I want to be lower.

Chris Case 28:32

Yeah, what I mean in the grand context of your quote unquote “career” here is that you’re not probably going to return to the level you were at six years ago.

Trevor Connor 28:42

Which is another nice thing about this take it in steps and a gap analysis and goals are about this year, because, yeah, what I will identify as the next level for me, what identify as goals are still way below where I used to be. But you can still have excitement to say, here’s where I’m at this year, and here’s where I can improve this year. Then it’s positive.

What is your next level?

Trevor Connor 29:05

So the next step in the gap analysis is what is your next level? And again, succinct, one sentence, and this is what is a level that is achievable this year? So a bad – if you said my current level is I’m a middle of the pack cat four rider, my next level is Olympic gold medalist.

Chris Case 29:29

Yeah, a little bit of a stretch.

Trevor Connor 29:30

I’m gonna go maybe you’ll get there, but not this year. You want it to not be overly ambitious, but you also don’t want it to be under ambitious. So if you said right now I finished about 50th in the cat threes, to say my next level is finishing about 40th in the the cat threes –

Chris Case 29:52

Not ambitious enough

Trevor Connor 29:54

Right. So you might go from I’m middle of the pack cat threes to I’m finishing with the lead group in the cat threes. And then the following year might be I’m winning cat three races. These are the steps.

Trevor Connor 30:06

So a good next level is ambitious, but achievable in a season. And again, be honest, keep it succinct, one sentence. The more you write out your current and next level, the more dishonest you get with yourself. So it’s got to be one sentence, succinct.

What separates you from the next level?

Trevor Connor 30:29

Then the next part, and this is the hardest part, this is what I send back to my athletes again and again and again and again, to redo is the what separates you from the next level. So it’s asking the question, you’ve identified your current level, you’ve identified the next level, why are you not already at the next level? What is separating you from that? And this is identifying the problems, not the solutions.

Chris Case 30:56

So you wouldn’t say, “Oh, it’s my one two minute power here,” you might say, “Oh, the difference between being middle of the pack and top 20, or podium, or top 10, or whatever the case may be is…” Give us an example.

Trevor Connor 31:12

There are tons of examples, but before I give an example, let me just say what I tend to find with athletes is when you are new to the sport, it’s mostly just training. It’s mostly just, I need to work on this side of my fitness or I have this issue of my fitness, that issue my fitness. As you get to higher and higher levels, you have to be more creative. You get into mindset, get into nutrition, get into preparation.

Chris Case 31:36

Do you allow people to use personal life or home life as a gap.

Trevor Connor 31:41

So I just got a gap a couple days ago from an athlete that I’m working with who has a very stressful job that prevents her from get into her training a lot. So her gap is “I’m not able to put in sufficient time to train.”

Chris Case 32:00

I figured as much, because that is a very critical and significant component to a lot of people’s lives – it’s outside of the training they get to.

Trevor Connor 32:11

I have some examples here that I send to my athletes, good examples of gaps are, “I can’t hang on the longer climbs.” Or “I struggled to stay at the front of the field and last few miles of a race.” Or “I don’t seem to have the strength endurance to last in a three hour race.” Those were very race focus, again, not everybody is a racer, but you can still do similar things. But notice that just saying, here’s what I’m noticing, here’s the issues. It’s not the solution.

Trevor Connor 32:40

Here’s examples of what not to write, “I need to raise my functional threshold power,” “I need to lose weight,” “I want to improve my….” So if you start your gap with, “I want.,” “I need”-

Chris Case 32:54

Red flag that those are not phrased correctly, those are not exactly gaps that we’re looking for.

Trevor Connor 32:59

And I’m sure a bunch of people are listening to this and cringing and going, “But we always have to focus on solutions.” And I agree we want to get to the solutions. But you can’t get to the solution until you know the problem. Mm hmm. So we’re identifying the problem. So this is doing all these things that sports psychologists and business school have told you not to do. Your statement should be things like “I can’t,” “I struggle,” “I don’t.”

Chris Case 33:23

Do you have any recollection of the weirdest gaps that you’ve received? Because I want some, I want some weird gaps.

Trevor Connor 33:33

Well, I will tell you one story.

Chris Case 33:35

Okay, good. Story, time is fun.

Trevor Connor 33:37

I am reluctant to tell, this was this poor soul that was in Victoria when I was training there and he used to come on our group rides and he was convinced that he was Canada’s top cyclist and he was going to the Olympics. Now he was he was a decent cyclists, I’d say he was a kind of middle of the pack cat two rider. But the difference between a middle of the pack cat two rider and an Olympic champion is unfortunately a very, very big gap. And I admire him for his convictions that he was Canada’s best cyclist and going to the Olympics. But this gets into that being realistic with yourself.

Trevor Connor 34:19

When we would go out in the group rides, we would hit these long climbs and because we were out training, we all had it drilled in our head, you don’t hit the hills hard, you just keep up the tempo, the perceived effort. So as soon as we would hit a hill, he would get to the front of the pack and try to drive the pace and we would all be like no, we’re not racing, this is training. So we would let him go. So he started claiming that he was the top climber in Victoria. However, there would be periodic times where as we’re getting closer to the season, we would hit the hills hard. So halfway up, we would start standing up and racing it and he would get dropped. So admiring the courage of his convictions, instead of changing his phrase that maybe I’m not the best climber in Victoria, he said, “I am the best seated climber.” So his gap was he is not yet the best.

Chris Case 35:24

I struggled at competing when you’re allowed to stand on your bike. Very interesting

Trevor Connor 35:30

That was one of the more unique, but that was, unfortunately, using gap analysis to maintain a bit of a misconception about where he was at.

Chris Case 35:42

Anything else for this portion about gap analysis, Trevor?

Trevor Connor 35:47

Yeah, that’s a good question. So I do have an optional part that I added to the gap analysis for my athletes. I didn’t originally have this, but just because of exactly what you’re asking, I felt it was important to have. Which is after they would do the gap analysis, I would have them answer the question: Looking at the next level, is that achievable this year? Some athletes skip that part. But it is good to have them do that part because I have had them sometimes go “No, actually, I think the amount of work, the amount of time that’s required, I can’t do. So that next level isn’t achievable.”

Trevor Connor 36:24

So I have an athlete right now I’m working with and she really wants to raise her level, she’s about to enter the the 60 plus category, and really wants to race strong in that level. She’s not going to be 60 plus this year, so she was identifying the next level for where she wants to be when she’s 60 plus and then we went through that. And I said, is that achievable this year? And she went “Actually” – the year she turns 60, she’s on sabbatical – she’s like, “It’ll be very achievable that year, but this year, no.” So we actually then had to go back and revise her gap analysis to say what is achievable this year. And ultimately, it’s never fun to do this, and her gap analysis, she basically said next level is just to maintain form this year, so that next year, I can hit that higher level. So it is important to look at this and always ask that question of “Do I have the time? Do I have the resources to actually” – mean you might physiologically be able to hit that level, but do other factors preventing you from getting there?

Chris Case 37:27

Right. So that seems a little contradictory in that you want to I mean, we haven’t gotten to goal setting here, you’re saying this is my current level, this is the next level. The next level, just to clarify, isn’t necessarily your goal for that season, next level is just what you’ve identified as –

Trevor Connor 37:51

Well, no, it should be, as I said, the next level is something that should be achievable in a season, ambitious, but achievable.

Chris Case 38:01

But you just said that she said she couldn’t do it.

Trevor Connor 38:04

So this is why I have that optional assessment is – so this is the good old all things being equal, if she could go and train hard. Then it is achievable. So this is just going back and reassessing again. Does life actually allow you to achieve this? So yeah, I could set a next level for myself that is achievable. That’s getting me back to where I used to be. But if I did the assessment on the feasibility, I’d have the same thing with the hours that I’m putting in at work, if I wasn’t doing those hours, yes, this would be achievable. But with the hours I’m doing no, it’s not achievable. So sometimes that’s not always factored in. So that’s why it’s an optional, because the gap analysis is so important, it’s just another way to look at it and assess whether this is truly doable or not.

Step Three: Goal Setting

Chris Case 38:59

Well, I think it’s time we move on to goal setting, the part that probably everybody really wants to get to, but those other two steps are incredibly important. But here we are goal setting. What’s it all about, Trevor?

Trevor Connor 39:14

So I’m going to start this and then Ryan can finish it because we both categorize our goals, and he has a few more categories than I do. So I always have my athletes break goals into two types, performance goals, and training goals.

Performance goals

Trevor Connor 39:31

So I’ll start with the performance goals. These are things that you want to achieve this season. Now they are often very race focused. It can be “I want to win race x,” or “I would like to finish on the podium in a cat three race.” Typically that’s what athletes give. But even if you don’t race, you can still come up with a performance goal. So it might be you want to PR a particular climb. It might be you want to finish an event that you were never able to finish. They don’t always have to be results oriented. They don’t always have to be a race. But think of this as this is what you want to accomplish this year.

Chris Case 40:14

This could be a weight thing, too?

Chris Case 40:16

Well, no.

40:17

Training goals

Chris Case 40:17

No?

Trevor Connor 40:18

Not in performance. So that gets us to the other type of goal, which is training goals.

Chris Case 40:23

I see.

Trevor Connor 40:24

And this is where you would put weight. So training goals are what you need to accomplish in your training in order to be able to accomplish your performance goals. So easy example, if you wanted to win nationals time trial, there’s a real ambitious goal for you, you want to win the Nationals time trial, I want to see some training goals related to raising your threshold power, improving your ability to hold an aerodynamic position on a bike, things like that. So these aren’t performance accomplishments, but these are the things that you need to accomplish to get to those performance goals.

Trevor Connor 41:02

Now, here is where this all kind of comes around full circle and where goal setting actually gets really easy. If you go back to your gap analysis, and you look at your next level that really defines your performance goals. So for example, if somebody said, next level for me is to be a contender in cat three races, then I want to see some performance goals related to finishing on the podium in cat three races.

Chris Case 41:34

And how specific do you want somebody to be? Do you want them to identify the race at which they think they have the best shot at performing that way? Or is it a bit more general?

Trevor Connor 41:46

I prefer general, I don’t mind athletes targeting a particular event, but if they do, I also want some general ones. Because my experience with athletes is when they target a specific event, very rarely do they accomplish their goals there. It’s usually like if an athlete says I really want to win this year, and I want to win this race, they don’t win that race. It’s usually a race that they don’t care as much about just because most people when they have that pressure on their shoulders, don’t perform as well. So they go to a race, they go, “Yeah, hey, this is just another race.” And all of a sudden, they’re in the breakaway, and all of a sudden they win the race. And then they look back on the season like “That was the highlight of my season.” So if you purely focus on one event, often that can lead to disappointment.

Trevor Connor 42:32

And the best example I have ever seen of this, or I shouldn’t say best, the worst example, I still feel for her is Erinne Willock, who went to the Olympics for Canada. She spent four years, all that mattered was the Olympics. And this was China. It was a 2008.

Chris Case 42:52

Yep, Beijing.

Trevor Connor 42:53

And it was a course tailor made for her. She was a phenomenal climber. And this had a big climb in it. She put aside everything to spend four years getting to the Olympics. The stories that she can tell about what it took to get to the Olympics, she could do a whole podcast on that. And she was at the Olympics. She was in the road race. They were coming into the final time up that big climb. She was sitting in about eighth wheel in perfect position, I mean, knowing how strong she is, I’ll say this and she’ll be more modest about it, but I’ll say she should have had a medal. But it was raining. And a less experienced woman was beside her, right as they hit the climb, that less experienced woman was riding on the painted line, fell over, landed on Erinne and ended Erinne’s race.

Chris Case 43:49

Yep, that’s bike racing.

Trevor Connor 43:50

That is bike race. That’s the danger of focus on a particular event. And Erinne came back. And I asked her about it later on. And she said I will never focus on one event again. And then the following year, she was the NRC champion.

Chris Case 44:06

The phrase putting all of your eggs in one basket comes to mind, you know, that can lead to disaster, they can all break at once.

Trevor Connor 44:13

So there is the danger of setting a goal of a single event. You could just get sick the week before that event not even go. So I mean, I always have my athletes at one or two A races, but we want other races. And the fact is I have them set A, B, and C races, I tend to find athletes perform their best at the C races.

Chris Case 44:34

Pressures off.

Trevor Connor 44:35

Yep. So yes, you can say I want to win race x, but I like it better when an athlete says something like, “I would like to win two cat three races this year”, because then we have a whole bunch of options, a whole bunch of opportunities.

Trevor Connor 44:51

So go back to your gap analysis, look at what you defined as the next level and then your performance goals should basically answer the question, “What do you have to accomplish in order to be able to say you reach that next level.” And those are your performance goals. It’s a really easy way to come up with your goals.

Trevor Connor 45:12

So then you’ve gone through this whole process of defining what is the next level for you, that’s ambitious, but accomplishable in a season, you’ve now set goals for the year that if you accomplish those goals, you can say I’ve achieved that next level. So this really directs your goals, as opposed to just coming up with arbitrary, “Well, I kind of like this race. So I’m going to set a goal of winning this race.” It’s more, this is next level for me, here’s what I have to do to get to that next level.

Trevor Connor 45:41

Training goals, this is where we start getting into solutions. Look back at your gaps, turn each one of those into a goal. What is the solution to that gap? And then make that a goal.

Trevor Connor 45:55

So let me give an example. You might have identified a gap as “I can’t keep up on on the long climbs.” So now you have to look at what is it that is preventing me from keeping up in the long climbs? Well, in this particular example, you might say I’m too heavy. Some athletes say that sometimes, but go “No, my body fats pretty low, I don’t want to lose any more weight, that’s not the solution.” Another potential solution is that you just don’t have the the power to keep up with the people that are winning those climbs. So this is where, if you’re talking about a long climb, you go, “Okay, I want to improve my sustainable threshold power”, because that’s what those climbs are done at. So you need to analyze that gap and start answering that question of how do I solve this particular gap? But go back to that example I gave at the very beginning, as sometimes people identify the wrong solution. So this is where you really need to dive into it and say, “what is the cause of that, that gap? And what is the solution to this?” And then turn that into a goal. And that’s where a coach can really help you. And they would you to describe that gap to them. And then they might be able to say, “Okay, here’s what I think is actually the solution to that that particular gap.”

Chris Case 47:20

This is probably a bit difficult to answer but, how long should somebody spend with this process? In your experience over time is this something that you sit down in a day and you finish it? Or is this something that you sit down once, you write some things out, you mull it over, you let it percolate in your mind, go on a few bike rides perhaps, come back to it next week, etc? What does it look like? What’s the timeline here?

Trevor Connor 47:49

When I go through this with an athlete, it’s quick, if we get it done in a month. I do it in the steps: first the season assessment, then the gap analysis and then the goals. And we don’t move on to the next one until the other one’s done. Each one, I’m going to have them go back through it a couple times. So write it, send it to me – I want them to not look at it for a few days, and then come back and revisit and then rework it.

Measurable goals

Trevor Connor 48:11

This is hard. As you saw, there’s lots of little nuances about gaps versus goals, how do you come up with goals? And before we move on, the last thing I will say about the goals is they all have to be concise, they all have to be measurable. Performance goals kind of have built in metrics. So if you had a performance goal of “I want to finish on the podium in a cat three race,” well, you have your metric. Training goals often don’t have a metric. So a bad training goal is “I want to improve my functional threshold power.” So you need to have a time period to it and you need to have a metric.

Chris Case 48:47

“I want to improve by 20%, or I want to get it to-” and a certain number.

Trevor Connor 48:51

“I want to improve my functional threshold power 20 watts, I want to have achieved that by April.” That’s a good goal. And I will often ask my athletes, let’s also attach to that a way that we can benchmark it. So to give you a good example, I was working with a time trialist who was actually focusing on the National time trials. So he wanted to improve his power. There was a weekly Time Trial series that he went to. So we added benchmarks to that goal of by April, we want you to be doing a time of x at that time trial. By May this. Ao we literally had an event that we used to use as a metric for the goal.

Chris Case 49:34

And that’s probably a pretty ideal situation to have that built into your season with checks like that.

Trevor Connor 49:40

Right. But you’d be surprised how often you can come up with checks. So if your goal is related to improving your climbing, well have a climb near you that you go and check yourself on periodically.

Chris Case 49:53

Yep, your test climb. article your test.

How to turn goals into actions with Coach Ryan Kohler

Chris Case 49:54

Alright, now we’re going to bring Coach Ryan Kohler in to discuss how to turn goals into actions. We’ll start by revisiting some of the key concepts we discussed with Trevor. Here we go.

Ryan Kohler 50:06

One of the key components here that we’ve seen throughout this is the value of the interaction and having someone assess that, like you said, Trevor, where they might take a few days to do this, and then it gets sent back to them with comments to keep reworking it. So really that value and having someone look over it can help you really get those those assessments dialed in. And I think with a lot of athletes, making sure that if you have a family, having that family involved; so you have your coach looking at it, you might have your spouse or someone else looking at that, and then they can actually help. I think they get that stuff dialed in too for those of us with the time limitations.

Ryan Kohler 50:45

I mean, that’s a big one. Say, I want to do this big race and my coach thinks I can do it, let me talk to my wife about this and see is it realistic? So I think it’s just the value of having essentially that whole team.

Chris Case 50:56

Yeah, I would think too, if you didn’t have a coach to volley this back and forth with, teammates would maybe be able to help you with your season assessment or your gap analysis and help you be even more honest with yourself. You might have a bit of a “Oh, I am really good at my sprint” and your teammates might be like, “Dude, you’re not very good with your sprint.” Like they might check that.

Ryan Kohler 51:23

Yeah, you have that impartial third person that’s gonna look at things and not – like, “We never see you up front. Why do you think you’re the best sprinter?” And they’ll tell you and it keeps the honesty there.

Trevor Connor 51:36

All of this has to be realistic. Or there’s no point to it. And having somebody check you on that, even if it’s hard to hear.

Chris Case 51:43

Yeah, it’s always nice to have a friend, colleague, family member or coach to look something over and give you feedback on it. Certainly in this context.

SMART goals

Ryan Kohler 51:56

The last piece, step three, where Trevor was finishing up with the goals, we have a few different ways to do this. And when I’m looking at goals with athletes I go toward, what we’ve all probably seen it around at some point, but that SMART goal assessment, you know, to kind of check yourself.

Chris Case 52:12

I don’t know what SMART means, tell me what SMART means

Trevor Connor 52:15

I know you don’t know what smart means, I’ve been telling you this for years.

Chris Case 52:18

Ohhhhh – tell us what SMART actually means, Ryan.

Ryan Kohler 52:22

Okay, so those letters stand for specific things that you can use to sort of check your goals and see if they’re realistic. So starting with the S, the S is specific: is it specific enough? This is part of Trevor’s goal setting too. With this, I’ll look at, “Pkay, what kinds of goals do we have?” So we may have some specific goals of” Yeah, I want to podium at this race.” But then we can also break these up into: are the outcome goals, are they process goals and that’ll help shape how we start looking at the process.

Chris Case 52:57

I’m playing devil’s advocate here, that’s not the best term, but for those that are really new to this, what’s the difference between an outcome goal and a process goal?

Ryan Kohler 53:05

An outcome might be something like, “I want to finish on the podium at x race.” And then, I think this was referenced in Trevor’s description too, of how do we get there? This would be like the training goal of: I need to reduce my body weight, so I can improve on these climbs. I’m going to focus on my nutrition and make some better food selections. And that might be getting us down that process of how we approach that. And I like how it allows us to also look at the big picture where we don’t focus on just like I need that one podium, or I need this national championship, but what are all of those habits that we can do throughout the season to help us move closer to that? And I think within the gap analysis, it helps us to see, okay, are we going from step A to B or C? Or are we trying to jump from A to M or N.

Trevor Connor 53:56

So I use performance and training goals. But this is basically the same thing, your outcome is your performance goals and your process is your training goals? Same idea.

Chris Case 54:06

Just wanted to clarify.

Ryan Kohler 54:07

So then the M would be measurable. So is it something we can measure? And again, we’ve talked about this. Ae need something we can measure and track and allow ourselves to benchmark our progress. So if we know that we’re making progress toward this, then it’s that nice, positive feedback loop to keep us moving in the right direction. And if not, then we bring back that honesty to say, “Okay, I didn’t achieve that. What prevented that? What can I do better?” Then we maybe change it, tweak it a little bit, and then keep on moving forward.

Ryan Kohler 54:36

So then the A would be achievable. And we discussed this a little bit as well. Is it something achievable? I look at this as we don’t want it to be too easy, and we can have a mixture of some that we think might be easier to achieve and others that are a bit of a stretch, but I like those stretch goals because they give us something to shoot for. And of course if it’s “I want to wear the yellow jersey and I’m a 40 year old, cat five on the road, that’s too much. So unless it’s not the Tour yellow jersey, could just go buy a jersey.

Chris Case 55:07

That takes different means.

Ryan Kohler 55:09

Yes. But yeah, just looking at the range of goals that we can set. And with achievable is sort of a sliding scale.

Ryan Kohler 55:16

R, realistic. Is it a realistic goal? Is it something that revolves around our current habits? Does it fit within our lifestyle?

Ryan Kohler 55:24

And then finally, the T, is it time bound? Do we have those those timeframes built in? And what is it going to take? We want to raise our FTP 20% and we set that goal for three weeks out? Probably not. But what’s a realistic timeframe for that? And that’s where we can have teammates, coaches, other third parties that maybe have done this before, have this understanding of, “Hey, I want to increase my FTP by 20% this year.” Your coach would probably have a good sense for how much time that would actually take. You throw a goal out there and they may say, “Oh, that’s a four year plan, Let’s save that and let’s find something we can do within this one year plan.”

Ryan Kohler 56:04

So that’s kind of the my way of going through and just figuring out how reasonable everything is. Does it make sense within our lifestyle?

Chris Case 56:12

Well, this begs the question, Ryan, Trevor, we’ve done all of this assessment and analysis, how do we take all this information and incorporate it into a training plan?

How to incorporate goals into your training plan: Macro and Mesocycles

Ryan Kohler 56:25

Right, so then it’s a matter of taking all this information and actually breaking it down because it could feel a little bit overwhelming once we get all of this stuff. So we need to try to figure out how do put this into place.

Ryan Kohler 56:37

So my first step is looking at what are those goals. So if we’ve done our gap analysis, and we’ve come out with our goals, how do we lay these out? I have a couple different names that I’ll throw in there that differ slightly from Trevor’s, but one would be categorizing these goals. Like physical verse event goals. So that might be something like improving your power, podiuming, something like that. There’s a mental piece that I like to include, and that’ll fall in line with how I sort of evolved this process over the years. And then I’ll add in a nutritional or health side to it. So again, more sort of quality type of assessment there. And then we have targets. So that would be more specific things like I want to increase my power or weight to x, or something that can be measured.

Ryan Kohler 57:31

So then, like you said, how do we start breaking that down? The way my brain works, I like to really start to break these out. And that’s why, in this document at least, there’s tables because it just makes sense. I try to keep everything nice and clean looking. So we look at this, this macro cycle view for the whole season, and there’s a couple pieces to this, where we’ve got a timeframe, we have a goal, so we can choose one or more goals depending on how we think this might fit into the timeframe of the entire season, and then – Previously, this started off as a goals, expectationsm and outcome process, but over the years, that’s evolved where the expectations piece I sort of got rid of and started calling it more intentions. So it’s more goals, intentions, and outcomes. And really, once we write that goal down and put it in there, then previously, if we said, “Okay, these are my expectations,” then it’s a little bit heavier that way. We have this thing that at times if it becomes difficult to continue moving toward that, then it’s like a thing hanging on us and it can be stressful and just decrease our motivation a bit to keep moving toward it, or where we might just say, forget it, I’ll just move on.

Chris Case 58:46

It sounds like expectations are a bit of a stick, whereas intentions are a bit more of a carrot. Like it’s a positive spin. They’re not that different, but expectations can lead to pressure, intentions maybe less so.

Ryan Kohler 59:03

Yeah and I think with expectations, initially, it made sense because I was early in my coaching career when I thought of it this way; we have a goal as the coach, we would have some expectation of what this would look like, and that’s something we can help communicate back to the athlete. But then over time it did become more of a stick to say, “Okay, we didn’t achieve that, oh, well.” Now, does that just throw the whole season out out the door? Well, not necessarily. So thinking of it more as intentions, it’s more positive. These are the things that I can do. These are the ways I can adjust my lifestyle. These are some of the sacrifices I can make, that I feel good about, and I can start to move toward that goal.

Ryan Kohler 59:42

And then the outcomes finally would be – we can put down that these are the outcomes I would maybe expect to happen, we could use it in that sense. Say I’d like to be able to ride X amount of miles by the end of this block and we can also use it as an actual outcome. So it’s sort of plan versus actual in a way, where then once we get to the end of that block, we can actually go back and say, Okay, this is what worked well, this is actually what the outcome was. And then we can sort of do this mini assessment throughout the year too. And I found this with some of the the groups that I’ve coached, and in particular juniors, because they don’t necessarily stop to think about things, right? They’re just go go go. And putting those questions out there to them to say, okay, we’re doing some skills on the bike, we might do some laps in the pumptrack, for example, and then having them stop and think in this very small piece of time to say, “Okay, what went well? What did you feel happening there? What could you work on next time? So I think just inserting little bits and pieces into those smaller timeframes through the year can be helpful in getting the athlete to get used to thinking critically and thinking back on things and seeing what worked and what didn’t, and then help that progress.

Ryan Kohler 1:01:00

So that would be kind of the year. So we might break down, in that macro cycle – I have an example here with three meso cycles, and they’re roughly three to four months a piece – but that can, of course, be anything. So this example here is specific to an early summer race, right? So the first mezzo cycle is January through March, the second one is April, May, and June, and so on. And we just adjust these timeframes as necessary to suit, one, what we what were our goals are, and two when we’d like to have this performance occur. So like I said, this one’s just around a race.

Trevor Connor 1:01:39

A lot of people listening obviously can’t see this graph, and this is great graph that Ryan has put together, but what I really like about what you’re doing is, somebody can come up with very successful or very good goals for the season. But we all get trapped in that, “The seasons really long, it’s December, I don’t have to worry too much. I’m gonna accomplish that goal at some point.” And I’ve hit the end of a few seasons, or suddenly it’s September, I’m like, “Wait a minute, when were those goals supposed to happen?” It’s always something up ahead. And you don’t think as much about how do I get to that goal? So what Ryan has done here with this graph, is taken the year, broken it into these mesocycles. So it’s January to March, April to June, July to September, and then looks back on the goals for the season, and says if I’m going to accomplish these goals, here’s what I need to accomplish in January to March, here’s what I need to accomplish in April to June, to ultimately accomplish the bigger goals. So you’re breaking it down into, here’s how I’m gonna get there. By breaking into these cycles, you’re able to see all that and know what you need to accomplish by when.

Ryan Kohler 1:02:52

Okay, so we have our sort of big picture view there, where we’ve broken these into these mezzo cycles of a couple months at a time, the next step would be then taking each mesocycle of a few months, and breaking that into individual blocks. And so when we look at these, this may be a matter of weeks. It could be three, four or five weeks, whatever is appropriate, but then it allows us to dig that down a little bit deeper, and focus on more specific targets. So this is where we might have one training block of maybe three weeks, four weeks, and we can pick a particular task to work on. So it could be skill, it could be a piece of your fitness, but it helps us evolve the training program to suit those needs. And always asking the question of does this move me toward closer to that goal? And I like how as part of the coach and athlete relationship, then it allows you to have that give and take where as a coach, you’re saying, “Yeah, this is what I think we should do.” The athlete might say, “well, I’m over in the Pacific Northwest. And it’s rainy and cold right now. And I can’t get out to train outside to work on this skill, because our park is closed. Maybe we can work on something else?” So it gives us the ability to adjust those targets and say, Okay, well, we know we’re coming up on a different time of year in the next block, let’s just flip these around and allow us to just keep that good focus from block to block. So really trying to just prevent any of that sort of mindless piece where we just don’t know why we’re doing something. So I think it just always gives us purpose.

Ryan Kohler 1:04:26

And the same thing, I break this down into what’s the target for that block? What ability are we trying to develop? And then what are those intentions that we intend to do to help us accomplish that? So that may be a very specific task of doing something twice a week, you know, and that may be something that falls in line with family and life commitments to say, Yeah, I can do this. And I know those are key sessions.

Ryan Kohler 1:04:49

Finally the outcomes, then we say, “Well, if we do this, if we intend to do A, B, and C, then what would the outcome be? Okay, well, I would I would be cornering faster or I can climb faster on this segment and I might see a PR, and then at the end of that block, did we see it? Okay, great. If not, then how can we adjust and maybe build that into the next block. So then we just run through that for the different mezzo cycles through the year. And I think it’s just sort of this evolving process that follows us.

Ryan Kohler 1:05:19

Alright, so we’ll step back a little bit and walk you through the story of how this plays out in a specific example. So this is a mountain biker, we’ll call the mountain biker, Bob, maybe

Chris Case 1:05:32

MBB

Ryan Kohler 1:05:35

Alright, so MBB goes through this process. And we’re starting back at the beginning with this macro cycle view. So we’ve established some goals. And this is event specific. So in this macro cycle, which is going to be essentially our whole season, so that that macro cycle view is just the large big picture view, and when you hear that just think the whole season the whole year, right? So the macro cycles are broken down into mezzo cycles. And these are just now smaller components within that macro cycle. So these may be a few months at a time. So we might have mezzo cycle 1234, right? So Bob’s macrocycle has three mesocycles. This goes back from January until September in three different cycles, right? So January, through March, April, through June, July through September. And the goal race for Bob is in the middle of June. So the second mesocycle is April, May, and June. That’s where we’re going to see this goal. So initially, in the first mezzo cycle, we’ve got this timeframe of January through March. And we have a goal of improving FTP by 7%. We’re working on improving that sustainable power. So the intentions associated with this is I want to increase the sustained efforts, because I don’t tend to do much of this. So my intention is to spend more time just doing sustained efforts. So that becomes part of the training, increasing power to weight ratio is another one, I want to improve course stability. So how do I do that? I intend to go and do more strength training in the offseason and come in feeling strong.

Ryan Kohler 1:07:11

And we should notice that this is another thing where these intention should be something that we notice as a change to our normal routine. And then we have another one of remaining mentally fresh, right? So we can talk about how do we do that. I intend to sleep more and watch my sleep habits and that sleep hygiene. So we can identify some areas there to help that. Before we get to the outcomes. Let’s go and see how we broke this down.

Ryan Kohler 1:07:35

So if we go to this first mesocycle, in this example, we have three blocks, right? So we’re thinking about this mountain bike race that Bob’s getting ready for. And we have a couple different targets that we want to develop. So we’ve got the three blocks. So block one, one of these targets we have is increasing cornering speed, right? So that’s going to help our smoothness and our flow. And another one is more training related. And this falls back to some of our sleep habits and recovery. So this one we’re calling maintaining the consistency of training. Those are two targets we want to hit the intentions with this is practice cornering twice a week. So Bob’s going to go out and you know, go to the bike park or go to his local trails or just wherever you can, and find a place where you can challenge yourself and work on this cornering. So we’re going to do that twice a week. And then the other intention is just making time for exercise. So then we can dig into this a little bit more and say, Okay, we’ll make sure we get to bed by this time. So I’m going to make that time for exercise so that when I’m on the bike and training, I feel good.

Ryan Kohler 1:08:42

So with this one, we’ll jump to the outcomes of this first block. So what Bob notices is hey grabbing less break through the corners. That’s great. A little side note is that when I’m on switchbacks, I still get a little bit freaked out by those. So let’s continue to work on that. But we have this positive outcome, and then we’re able to find something to say, yeah, still kind of slow through those switchbacks. But that’s great, we can still work on it. Another one is only missing one session of that. So a great positive outcome, we hit the vast majority of our sessions, I missed one, but that’s part of it. And that’s why again, these are intentions, not expectations, we don’t need to stress about it. And think about was this still an improvement over the past? And if it was awesome, what’s great, now we have that positive feedback loop.

Ryan Kohler 1:09:25

So then the second block of training within this January, February, March timeframe, we’re looking at something a little bit more training related. So just spending this time at intensity, you know, we’re looking at some threshold riding, we’re trying to increase that from 30 minutes to 60 minutes. So now we’re going to start to do more of those sustained efforts. And we have a certain target in mind to just time at that intensity to increase it. So the intentions there are to recover and fuel for the key sessions. So we know our key sessions are going to be around some of that threshold work and sustainable work. We want to make sure that we recover for those and keep those as priorities during the week. So the outcome for this one is, hey, we worked up to three by 20 minutes at threshold. And we saw that we had we fueled Well, we hydrated, well, our heart rate was nice and stable through there. So those are some pretty nice outcomes that we can take and build on.

Ryan Kohler 1:10:18

So then we get to this third block in the first mezzo cycle. And we’re going to do some high intensity training. So we want to come to those well prepared, and we’re going to do some testing at the end of this. So I want to come in mentally fresh for this FTP test, because looking back, one of our goals is to increase FTP. So our intentions here, Bob’s gonna focus on sleep quality, and then a new thing that we’ll bring in is, hey, let’s, we haven’t talked about visualization. Let’s bring some of that and see about how can we come to these workouts well prepared? Well, let’s visualize that workout. What does it look like when we perform optimally? And when we when we have a good session? What does it look like? So that can be a visualization technique we can use? So outcomes for this block? Hey, we got consistent bedtime, and I feel like I slept better. I just woke up more refreshed in the mornings. Awesome. We did our FTP test, and we found his 5% increase. So did we hit that seven target? No, but that’s okay. We were pretty close.

Ryan Kohler 1:11:15

And it’s good progress. One of the things I always mentioned to athletes is from my adventure racing days, one of the key takeaways from adventure racing is constant forward progress or motion. And and I always tell this to athletes, when it’s, you know, we see something like this, maybe our FTP increased 5%, not 7%, that’s fine. It’s forward progress, if we can continue that progress, just like, you know, when you’re out in the middle of the woods, and you know, there’s six hours of hiking ahead of you, you’re gonna run into these mental valleys of despair. And as long as you keep moving, it doesn’t matter. If you’re moving at a mile and a half an hour or three miles an hour, as long as you’re moving, you’re making that progress. And you’re going to get to the next section. So I like to bring that into this process of goal setting and progressing through these. So that’s the end of that first mesocycle, we finished with that third block. And then of course, after that, we would continue on into mesocycle two and three. So use that example, you can build that in and dig into the further mezzo cycles as necessary. But that’s, that’s one. So that’s the third block of Bob’s first mesocycle, as an example, so you can then take that and build it into future mezzo cycles for two and three.

Chris Case 1:12:33

Great. Yeah, that’s a good example of walking through this process. It’s kind of an inverted triangle, I guess you could say where you’re starting with this big picture view, you’ve got some delineation of things there. But you really want to drill down and drill down to your mesocycle level. So you have a better understanding of where those stepping stones are to see that progress that move forward motion.

Ryan Kohler 1:12:58

Right? Yeah. And it just I think, helps me personally with the planning. And that’s one of the things that I learned early on in coaching is know why you’re doing something in training. And if you can’t answer that question of why you’re doing this, then figure it out or probably do something else.

Closing thoughts

Chris Case 1:13:14

That’s a great overview of this goal setting process. Ryan. Trevor, do you guys have any other final thoughts here?

Ryan Kohler 1:13:20

Yeah. So mostly knowing why you’re doing this have, you know, give yourself the time to put into this and, you know, make sure you have a resource to look at it, like Trevor said earlier. Understand what you’re trying to get out of this, take the time to put the information in there and don’t rush through it. You know, and I think that’ll really give you the the answers, you need to help develop that 30,000 foot view and guide your season.

Chris Case 1:13:47

Trevor?

Trevor Connor 1:13:48

So my one minute is, we covered a lot. And this all sounds very complex. And I know it’s an involved process. So really, what I want to get at here is, it is important to go through some sort of process, I highly recommend what we just described, because that’s really worked with my athletes. But I think if you start with assessing yourself, where you’re at where you’d like to get to, and then use that to direct your goals, you are a going to come up with goals that are more relevant. B) you’re going to come up with goals that are more realistic, and they’re going to set you up for a more successful season than just trying to randomly grab some goals that are out of context of where am I at? Where am I trying to get to? What am I capable of doing?

Chris Case 1:14:44

That was another episode of Fast Talk. Subscribe to Fast Talk. Wherever you prefer to find your favorite podcasts. Be sure to leave us a rating and review. The thoughts and opinions expressed on Fast Talk are those of the individual. As always, we’d love your feedback. So join us and join conversation at forums.fasttalklabs.com to discuss each and every episode, become a member of Fast Talk Laboratories at fasttalklabs.com/join and become a part of our education and coaching community for Ryan Kohler and Trevor Connor. I’m Chris case. Thanks for listening!