Listener Q&A on high intensity (HIIT vs. HIT), pyramid intervals vs. Tabata intervals, gut health, recovery, and CTL

Episode Transcript

Chris Case 00:14

Hello, and welcome to Fast Talk: Episode 112. A question and answer session with Coach Connor and I and yes, we’re sitting in the same room again, we’re on a streak, Mr. Connor.

Trevor Connor 00:27

We are, two days.

Chris Case 00:28

Two days in a row recording in a building with equipment. So today we want to cover some of your question and answers. I want to give an update as well first – Cycling in Alignment, the much anticipated podcast brought to us by our friend, fellow coach, fellow cycling-lover and thinker and tinkerer Colby Pierce – gonna be awesome. He’s got a great mind. He’s recorded a lot of good stuff already. I’ve heard it, you’re gonna love it.

Trevor Connor 01:04

We’re really excited about the show. As you know, we’ve had Colby on Fast Talk a ton of times, he always has great insights. He has perspectives that we don’t have, I tend to be kind of science heavy. He knows the science, but he has the holistic view on this. And I think it’s going to really add to what we’re offering with his show.

Chris Case 01:24

Yeah, you’ll see the the show art reflects a very tranquil philosophical perspective. If and when you listen to the first episode, get into your Zen place. This is – I’m trying to channel my inner Colby here – get into your Zen place, put your head down, relax, maybe even light just a single candle and listen to that episode. That’s the type – it’s awesome – it’ll get you into a great place. That’s, that’s, I’m hope, hopefully that appeals to people, appeal to me.

Trevor Connor 01:58

We’re excited.

Chris Case 01:59

Check out his podcast channel, now. It’s got a couple episodes already there. One, his introductory episode, he really talks about who he is, as an athlete, as a coach, why he’s doing a podcast, why he wants to give all this insight and discuss all these topics around cycling and holistic health. He also has a gripping conversation with Nathan Haas, one of his friends, somebody he’s known for a very long time, and who was stuck in Girona during lockdown in Spain so that is a another episode to check out right now. The other thing that we should mention about the show is that not only is he quite philosophical at times, he’s very knowledgeable about the science. And so you’ll hear him talk at length and in great depth about everything from pedaling dynamics to nutrition topics, and so forth. So he’s a great combination, a singular figure in the cycling world. One last thing, we’d love for you to check out a survey we’ve got running right now, go to fastlabs.com/subscriptionsurvey. We are considering a subscription model here at Fast Labs for some of the different offerings and some other things that we have in the works so we just want to get your feedback on what you’d like to see, what you’d be interested in subscribing to, other hosts for podcasts, other topics you’d like us to cover, and so forth. So please check it out, the address again, fastlabs.com/subscriptionsurvey. Thanks. So today’s episode, we’ve got a variety of questions from a variety of avenues. We’ve got email questions, we’ve got voicemail questions, we’ve got Twitter questions. We’ve got a homing pigeon question – no, we don’t have any homing pigeon questions – do we?

Trevor Connor 03:59

I hope not. I haven’t read my homing pigeon research in a while.

Pyramids and Tabatas

Chris Case 04:04

Okay, let’s, let’s get into it. Let’s get the first question. It comes from Ryan Bates in Ann Arbor, Michigan. He writes, “I am re-integrating some interval work back into my training plan following the polarized model you recommend. My typical HIIT workout is a so called Russian pyramid, which I like because it keeps things interesting. A pyramid starts at five seconds all out, 55 seconds, slow spin, then 10 seconds all out, 50 seconds, slow spin, etc., all the way up to a pyramid with 55 seconds all out and a five second slow spin and you end up with a full minute sprint. That takes about 12 minutes. If I’m feeling extra frisky, I’ll do two or three sets with three to five minutes rest between them. So he has two questions. A, is there any reason why Tabata style interval workout, 30-30s, 40-20s, would be any better or worse? And second question, is it wise to be doing multiple sets of these? Or should you be doing these intervals so hard that you can only do a single 10 to 12 minutes set? Trevor, what do you think?

Trevor Connor 05:24

First thought that came to my head reading this and when I replied to him is an expression which I’ve used a few times on the show, which I love to use with my athletes, which is, don’t let the perfect get in the way of the good enough. So I’ll give you my full answer on this but there is a difference between what is potentially optimal purely from a physiological standpoint and then what’s optimal from the bigger picture when you’re looking at motivation, execution, enjoyment, getting gains out of it. But let’s start with – he asked, his first question was, is there any benefit to Tabatas? So I think to answer our full, all these questions, I need to take a step back, give a quick Tabata history, which I think we’ve done on the show before.

Chris Case 06:15

Yeah, it’s worth reminding people though, it’s a good story.

Trevor Connor 06:18

Basically, Dr. Tabata was a researcher. He was looking into this whole concept of watt prime, this – how much what’s, what’s your energy capacity above threshold. And they were trying to figure out how to deplete it. And found that if you had – if you just told athletes go do a five, six minute all out effort and destroy yourself, it was actually really hard to do, because that is very, very demanding outside of a race situation. So they tried something different where they gave short, hard efforts – so the original Tabatas were 20-10s.

Chris Case 07:01

Mm hmm.

Trevor Connor 07:02

But a really short recovery. So you didn’t have a lot of time to recharge that energy.

Chris Case 07:08

Yeah, 20 seconds, hard, all out, full gas, as they say, 10 seconds recovery, right?

Trevor Connor 07:13

And then 20 seconds all out –

Chris Case 07:15

Which really isn’t enough for recovery, which is the point.

Trevor Connor 07:18

When you do these intervals by the time you get to the seventh eighth repetition, that 20 seconds feels like about a minute.

Chris Case 07:27

Yep.

Trevor Connor 07:27

And that 10 seconds feels like barely a breath.

Chris Case 07:30

Exactly, yes.

Trevor Connor 07:32

So they found it was very effective for what they were trying to research. They weren’t actually initially my understanding, trying to design a workout there.

Chris Case 07:45

It was for research purposes.

Trevor Connor 07:48

For research purposes – but then it turned into a workout. This was kind of a side benefit. People said, hey, look, actually, we, there’s training gain to depleting this. So watt prime – we’ve covered this before as well – it’s – a lot of people say, well, this is your anaerobic capacity, that’s not quite true, because it’s actually a measure of your capacity above threshold. And you still have a lot of aerobic energy above threshold so it’s a combination of all your anaerobic energy capacity, plus some aerobic energy capacity. But basically, it’s what you have when you’re going really hard, right. And when you, if you want to train it, you got to go really hard. And lo and behold, what they discovered for their study holds for training as well going and doing five, six minute, really hard efforts to destroy yourself, ain’t a lot of fun, it’s hard to do training, going and doing the 20-10s for some reason, we can just beat ourselves up better – so it made for a good workout. So is it better than what he is doing? Is it better than a pyramid or are his pyramids better? I’m first going to give you my bias, which is – I like to design workouts that target energy systems. I don’t like high intensity workouts where you hit every energy system under the sun because I feel that there’s – that can only go one of two ways. One is you only sort of hit every energy system and no energy system gets enough of a stressor to really get a gain out of it.

Chris Case 09:24

It’s a bit of a compromise on all of them.

Trevor Connor 09:26

Right, or, alternatively, you do such an incredibly hard workout to do actually stress every energy system and then you can’t get out of bed for five days. Neither one’s a great option – so I’m generally big on have a workout that targets one, maybe two energy systems and really hone in. So pyramids, especially those pyramids that start with like a five minute effort, then a two minute or four minute effort, go all the way down to a 15 second effort just run too much of a gambit for me. The one exception I’ll give as you’re getting into the season – well, that’s a race as our races, you’re doing a bunch of efforts in a bunch of different energy systems so it’s a great way to get some race specificity before you race. So that is the one place I would use that sort of pyramid. But as a regular training routine to use for a long period of time to build specific assets, I don’t love them personally. I do like the Tabatas because they really do target that very specific energy system. That’s, that’s what they were designed for.

Chris Case 10:35

But you would also use them pretty sparingly.

Trevor Connor 10:38

I don’t have to – no Tabatas in December – I look back, like I use them myself, I’ve been using them for years. And at one point I was going “am I breaking my own rules here? Am I doing them for too much for too long?” And look back and even my best seasons because they are so hard, because they’re so damaging, I was finding that I would start them before the race season, just before the race season and do them through the first part of the race season. And I would do a count and I might do six to nine total Tabata workouts.

Chris Case 11:17

Mm hmm.

Trevor Connor 11:17

Yeah. So not a lot.

Chris Case 11:20

Yep. Well, you don’t, once you do one of them, you’ll realize that you don’t want to do that many of them.

Trevor Connor 11:26

They’re tough. They’re tough. They’re not all that fun. So that said, looking at Ryan’s pyramid workout, it’s all under a minute efforts – so it’s all getting into that above threshold, really beating yourself up type work. So it still is more one or two energy systems than a lot of the classic pyramids – so I don’t mind it. So it, like Tabatas, is honing in on that trying to hit that watt prime, trying to deplete that anaerobic capacity. Is it better than Tabatas? Is it worse than Tabatas? Well, this gets back to my original point, we could probably split hairs and say, well, Tabatas are more specific. We could say talk about specifics of the execution of the pyramids. But ultimately, my answer and this is the answer I emailed back to him is Tabatas does really suck. They hurt yet these pyramids probably really hurt if you’re doing them, right.

Chris Case 12:32

But-

Trevor Connor 12:33

But exactly. If you are getting on your bike and going out and going, I will I am going to find any way possible not to do these 20-10s, but I enjoy these pyramids. Even if they’re not quite as good, if you are motivated, if you enjoy them, this stuff hurts. Go do what’s fun.

Chris Case 12:55

Yeah, right.

Trevor Connor 12:56

What uh, my original mentor – brought him up a bunch of times on the show, Glen Swan, he was a fantastic cyclist. He tried intervals, one – went once and went, well, those suck and never want to do those. So he set up a Tuesday night training race and he would go to the training race and just sit there and attack the field and get caught then attack the field. And if he was, he was low tech, he didn’t record any of his workouts, but had he had a power meter and recorded it, I imagine the profile of those Tuesday night races probably looked a lot like Tabatas. But it was just his way of getting that super high intensity in a way that was he was motivated and enjoyed. And he always said that, to me. It’s like I said of those Tuesday night races because I can’t go that hard by myself.

Chris Case 13:45

Right. He needed that context. And some people could do probably use Zwift in that same way.

Trevor Connor 13:52

Right, exactly. So my answer to this is – if you – the question in terms of physiology, which is better? We could probably make an argument that the Tabatas are a little better. But if you enjoy those pyramids, if you go out and rip yourself apart, and you’re motivated to do that, as a coach, I would be telling you Yeah, go do that. In terms of how many sets should he be doing? That’s very individual. It also depends on the level of the athlete. For a lot of athletes, one set is quite fine. When you start getting up the pro level, no, they’re probably going to need a few sets. I will say if you are doing four sets of those pyramids, you’re probably not going hard.

Chris Case 14:40

Yeah, right, that’s pretty clear. If you’re able to get through four of these sets, which we’ve already described as pretty awful, then you’re not doing any of the four hard enough.

Trevor Connor 14:52

Right. Right. So two a really good day, get through three or half of the third – probably a good it was probably a good day on the bike. They’ve done research on benefits of additional sets. It’s been more in the weight room but a lot of the same principles apply to high intensity work on the bike. And believe it or not, you get about 80% of your gains from the first set so it is a law of depreciating returns. And it’s a very steep curve.

Chris Case 15:26

Yeah, yeah

Trevor Connor 15:27

So, you if you go out and just do one set, but do it really well, have a hard workout, you’re getting most of your gains?

Where Does High Intensity Begin?

Chris Case 15:36

All right, let’s take our next question. And this one comes from Google Voice – and I want to point out to our listeners out there, while we’ve enjoyed using Google Voice, we’re actually going to stop using Google Voice. But we still want to hear your voice recorded, and put that into our Q&A episodes. So what we want you to do, record yourself on your voice memo app on your own phone, do it as many times as you need to to get it right. And then send it to us, email us at fasttalk@fastlabs.com – should be pretty straightforward. Alright, let’s get to the question from Doug. in Rochester, New York. Here it is.

Doug. R from New York 16:20

Hi, this is Doug Rochelle from Rochester, New York. And my question is, your opinion, what is high intensity in terms of where does it start? Is it threshold? Is it you know, VO2 max, anarobic capacity or muscular power? And based on that answer, when you’re referring to springtime heroes who then turn into July zeros and saying that they do too much intensity – exactly how much is that on a weekly basis, specifically during a base period and say January or February? Thanks!

Chris Case 16:50

Trevor, what do you think?

Trevor Connor 16:52

I had fun with this one last night – and I am just noticing that in his question, he never actually specifically used the terms HIT and HIIT. Chris and I discussed this question and brought those up. He did ask about high intensity training and so I had so much fun researching HIT and HIIT we’re going to answer those anyway.

Chris Case 17:17

Yeah, absolutely. It’s good context for the question.

Trevor Connor 17:20

Have a little fun with it. So you will hear these two terms a lot so or – you’ll hear people talk about “hit” training. So let’s quickly give the definitions – this will be the clearest thing that I will say for a while now. HIT stands for high intensity training. HIIT stands for high intensity interval training.

Chris Case 17:43

And let me guess, they’re not the same thing.

Trevor Connor 17:45

Well – you think it’s gonna be that clear and simple?

Chris Case 17:50

Well, all right. Let’s get – let’s to the muddy part.

Trevor Connor 17:53

You asked me about them yesterday, they are used a lot in the research. So I went well, that’s obvious and then start to give you a muddled answered and I went maybe that’s not quite as obvious as I thought. So I had some fun last night and I did a Google search on it. And by the end of the Google search, I was completely confused. That was a poor choice on my part.

Chris Case 18:14

Did you – did you reference any of your textbooks that you go to?

Trevor Connor 18:20

I did go to PubMed and look at research and we’ll we’ll finish with that.

Chris Case 18:24

Okay, good.

Trevor Connor 18:24

Because that’s kind of where I stand. But first let’s start first with what you see if you’re just going to websites talking about training, you know, basically the standard Google Search which is – it is all over the bloody map.

Chris Case 18:40

Hmm.

Trevor Connor 18:42

So I found … sorry, it’s all all over – the nice clean clear map –

Chris Case 18:49

No, I just – I like the term bloody, it’s not used nearly enough in North America. The Brits use it a lot. There’s a British influence in Canada. You use it some?

Trevor Connor 18:59

I use it a lot. That’s a good point. I never thought about that.

Chris Case 19:02

We don’t use it down here very much at all.

Trevor Connor 19:04

Yeah, I use it a fair amount in Canada.

Chris Case 19:07

All right, let’s bring it back. It’s popularized in Boulder

Trevor Connor 19:10

Its our thing now.

Chris Case 19:10

Bloody Boulder.

Trevor Connor 19:12

Bloody Fast Talk

Chris Case 19:13

Bloody Fast Talk – **** – can I say that on the air – ****?

Trevor Connor 19:17

No, no.

Chris Case 19:20

I thought that was like a sausage or something over in the UK right?

Trevor Connor 19:24

Now that we’ve confused people with the term bloody let’s get into the confusing germs of HIT and HIIT.

Chris Case 19:29

Very good. Let’s do it.

Trevor Connor 19:30

So one website – and I’m not going to give these huge URLs – differentiate them by saying one is endurance related and said that HIIT involves resistance – no, actually, the first one said that HIT involves resistance training and HIIT is endurance work or cardio work. Second one said HIT resistance training gives gains of cardiovascular work in seconds. So it’s basically their argument is that you go do some high intensity – the good old, you can get all the cardio gains and seven minutes and that’s using the “hit” work. My, my favorite, which I’m going to read their description because I don’t know how to explain this – says is there actually a difference between HIT and HIIT or are it just different spellings of the fitness trend that has become so popular in recent years? Clearly, this is actually two different training forms – both have one thing in common, namely the extremely high intensity, but the one, HIT is used in the sport and the other, HIIT, rather in the area of endurance sport.

Chris Case 20:50

That – that doesn’t sound like somebody with English as their first language wrote that.

Trevor Connor 20:58

I don’t know. But that was one of the first things that come up in a Google search asking the difference between HIT and HIIT.

Chris Case 21:05

Point being there’s some confusion out there.

Trevor Connor 21:10

So what I got from when you are looking at it in kind of the common what people think of – not just in the cycling world, but in the sports world in general – I actually found an article on Penn Medicine News and it says “the workout debate: experts weigh in on cardio versus HIIT” and they ask a whole bunch of trainers, physiologists, the differences, and they all said similar things. And I’m just going to read one, which is a celebrity fitness trainer Jillian Michaels explained to the Insider why cardio, in this case running, is the least efficient form of exercise saying in the piece, “this is because cardio is not metabolic meaning it doesn’t cause the body continue to burn calories post workout”. Strength training, on the other hand, causes the body to burn calories both during and after workout. So in clinical terms, HIIT it is really better than traditional cardiovascular exercise, and basic – so I’m not going to keep reading but goes on to – several the experts say basically HIT training is more efficient, you’re gonna burn more, you’re gonna get more gains in less time than what they’re calling traditional cardio. So that’s kind of the what you’re going to see a lot out on the web. If you go to PubMed and look at the research, what I am finding is there were a few studies that differentiated HIT from HIIT. But for the most part, they’re used interchangeably from basically very high intensity work that involves at inv some sort of interval structure. And what they differentiate is HIT work from LIT work from MCT – so LIT work is low intensity training – that’s your long slow zone one, zone two rides. An MCT, well, if you look it up on the web, I just discovered it stands for marine combat training – but I don’t think that’s what they’re referring to in the research, right? This is moderate consistent training – so it’s that sweet spot or long threshold-y type work. But yeah, kind of that in-between the few studies that I did find that differentiate them, HIT involves some sort of interval structure where they were talking about HIT being still high intensity threshold or above, but being constant. So if you’re going out and doing Tabatas, that’s HIIT, if you’re doing sprints that’s HIIT, if you go and do a threshold climb up a 40 minute climb, they might call it HIT but for the most part, the research seems to use those two pretty interchangeably. So what is high intensity?

Chris Case 24:05

Yeah, back to back to Doug’s question about where, what is high intensity? Where does it start, so forth.

Trevor Connor 24:12

So remember, we did do an episode where we said, Look, there’s not this black and white, you’re one beat per minute above threshold so now you are doing this type of training, you’re one beat per minute below threshold, now you’re doing that, over five watts below five watts above. It is a continuum. So high intensity training, think of it as threshold and above. But I’m still going to say if you’re a little bit below threshold, so we talked about those time trialers going and doing 95% threshold, big gear type work, I would still call that high intensity work. But it’s when you are doing threshold or above interval type work, you’re doing high intensity training

Chris Case 24:59

And obviously, you’re talking about above anaerobic threshold here?

Trevor Connor 25:04

Yes. Yes, not above the aerobic threshold, LIT would be a robot threshold or below and that MCT would be that in between range or what are more commonly termed sweet spot, right. Going back to his question I loved, I actually haven’t heard it turn this way but referring to springtime heroes who then turned into July zeros – thank you for sharing that. I haven’t heard that one.

Chris Case 25:30

It’s a good one.

Trevor Connor 25:32

So he said exactly how much is that on a weekly basis, specifically during base period and say, January or February. So this again, depends on who you’re going to – who you talk to. We’ve brought this up many times that we have a polarized bias. There are lots of people out there that have a high intensity bias, there are lots of people out there that have a sweet spot bias. So if you are talking to people who have that more sweetspot bias, they’re going to tell you, not a ton of HIT, not a ton of LIT, biggest bang for the buck is that MCT, sitting that in between range, and they’re going to tell you because it isn’t as damaging so you can keep doing it day after day. But you’re going to get a lot more gains in the long and slow. So you should do a lot of that. Polarize model is basically saying all your time is either above anaerobic threshold, or below robot’s threshold, avoid that in between, that HIT work is very damaging. So generally, if you’re talking on a weekly basis, it’s two sessions per week. And we’ve already had that talk about maybe a week is not the best way to map things out. 10 days is better. And you’re looking at two sessions for 10 days, something like that. But it’s infrequent, high intensity work that make it hard. And the rest of your time is in that LIT range. There is the time crunch approach, which is you spend very little time on the bike and this is I was quoting all those websites, That’s basically what they’re saying, They’re saying, why would you waste all this time going out and doing long and slow? Train four or five hours a week and do nothing but high intensity and you’ll be a superstar! I would say if you are somebody who’s just looking to be sort of fit and lose some weight, there’s probably some validity to that, if you are actually an athlete trying to train for performance, I don’t think that’s gonna get you very far.

Chris Case 27:39

Our next question comes from Ariana in Sereno, Italy. And she asks, how can I effectively use this time during stay at home orders as an opportunity to give my body a break from constantly high carb intake and improve the state of my gut? Well, we actually had Petr Vakoc, a pro rider on the phone recently, he’s with the Allison Phoenix team. Petr also stuck inside right now at his training base and in Andorra dealing with this very issue. So we asked him this question, and here it is, here’s his answer.

Improving Gut Health During Covid

Petr Vakoc 28:25

Yeah, that’s exactly what I’m trying to do because, like, based on my experience, I’m not hundred percent sure but I believe it’s mainly the high amount of fructose that I consume during the races or even during the hard trainings, that’s, which is the main cause of my digestive issues. But I think in general, like eating so many carbs, and especially so much of simple sugars, so this is a perfect time to get most of it and focus on eating real food, which also has the benefit of filling you more, I would say, because now, probably for most of the people, the training volume is quite limited, and the intensity as well as there are no no real ghosts on the horizon. So it’s an opportunity to give the body a little bit of a break and opportunity to heal up. I would say some of the damage that that’s caused by the nutrition that’s necessary for the for the highest performance. So for me it is just to eat as much food in the natural forms and limit the sugars as much as possible. I still consume some around some of the more intensive trainings, but also what I tried to do, and I will just use maltodextrin instead of the glucose fructose combination to really get the fructose and see if if that’s the case. And if it helps, and yeah, the moment with, like the generally very healthy nutrition that I’m trying to follow now. I have the benefit will be also before I would say some, yeah, longer term healing effect on the gut, and hopefully less digestive issues when we are back in the racing times.

Chris Case 30:52

Anything to add to this answer, Trevor?

Trevor Connor 30:56

I’m just gonna add given a little bit of my bias, which as you know, I don’t think the super high carbohydrate diet is that performance enhancing.

Chris Case 31:05

Mm hmm.

Trevor Connor 31:06

And I used to be a huge proponent, proponent of the high carbohydrate. I’m not going to get on the ketogenic avoid carbohydrate camp either. But I think there’s a balance, the main thing I am going to add is, and again, you are getting my bias. I don’t like the constant trend of high carb, low carb, high fat, low fat. That’s not how our bodies function. The question is, what are you eating? What are the sources of those carbohydrates? It’s not important, whether it’s high or low, but what are you eating? So people tend to when you hear carbohydrates, you tend to think, well, breads and pasta. Fruits and vegetables are carbohydrates, candies are carbohydrates. So you can eat a high carbohydrate diet, that’s all candy and crappy pasta or you can eat a high carbohydrate diet that’s based more on a lot of fruit and vegetables, and they’re gonna have very different impact on your health.

Chris Case 32:10

Yeah, I mean, the, the, the, to have the carbohydrates, but one lacks pretty much anything else, and the other has a lot of these other key nutrients that you need to thrive.

Trevor Connor 32:22

So my answer to this question is, I don’t think now you need to go low carb – or, I would just get away from that mindset of high carb, low carb, more think about, let’s get some quality, high nutrient density foods, you know, by it. And I think once you get back to full training and racing, that should still be your bias.

Chris Case 32:46

Right. You could use this opportunity as a bit of a reset, if you’ve previously been with that mindset of I must have high carbohydrate diet, and we’re talking sort of the stereotypical high carbohydrate diet with, with breads and pastas to perform on the bike. But use this time right now, maybe you’re not riding as much or maybe you can’t ride outside as much, reset your body, eat more of a healthier diet with more fruits and vegetables, etc. cut down on the carbohydrate level to some degree, and then continue that into racing and training and see that you can actually perform just as well, if not better with that diet.

Trevor Connor 33:33

I remember a couple years ago, I listened to a podcast interviewing a well known ex-pro, who has been on the podium at a grand tour, and they were talking about diet and doping. And he had a very cynical view saying to perform at this level, you have to eat a horrible diet. We all ate crappy. And that was part of his justification for why they needed to dope. And I am going to again, give my bias which I think that is pure BS. Yeah, I think it is possible to eat a healthy diet and perform at that level. They just didn’t do that. And probably had they been eating healthier, they would have recovered better and possibly could have performed and certainly not the level they were performing that then – that was just not physiological. That could have performed at a high level with a healthier diet.

Recovery, Explained

Chris Case 34:26

Yeah. Well, let’s close out the episode with a couple questions that reference back to our last q&a episode, where we dove deep into TSS CTL as well. Let’s first hear from Ben Guernsey who asked us about TSS and recovery. What tools can you use to help with that? Recovery is super important, as we all know by now, I recall Trevor talking about a study in an early episode about how athletes have a national federation would take their resting heart rate in the morning to know how to train that day. So when it comes to larger rest blocks, do I need to schedule in a full week? Or with new HRV technology like Whoop, is it a better use of time to recover until my HRV is back up, well into the green? Is there any evidence extra days of being well recovered have some benefit of additional repair, rebuilding? Or is this just wasting days that one could get back to training? I tend to have my TSS on a rest week trying to, quote stir the pot with activities, no weights or intensity. Besides serious injury or illness or illness, is there ever a time to go quote full couch potato? Trevor, what do you think?

Trevor Connor 35:45

I love recovery questions. That’s the first thing I’m gonna say love recovery questions. Recovery is so important and so overlooked. So Ben, thank you. I love that you asked this. The very short answer to your question is that, yes, additional days, there are no additional gains, there’s a certain point where you flip over from recovering to simply detraining. But that comes with a giant qualifier of it’s very hard to know when that point is and my experience with most athletes is they don’t get to that point, they tend to stop the recovery phase too early. And I, particularly when I’ve had an athlete really fatigue, and I want them to do a proper recovery, I would rather have them err on the side of recovering too much than too little. So let’s dive into this ways of knowing and he brought up Whoop so let’s talk a little bit about heart rate variability and how to use that. And one other thing I’m going to point out here, as I’m talking about true recovery weeks, I’m not talking about you did an interval session yesterday so now you’re doing a recovery day, today I’m talking about, you just finished a giant stage race, or you just finished a big training camp and now you want to do a true recovery week to let your body come back up. When I give my athletes that week, the way I describe it to them is you’re after a couple days, you’re going to feel pretty good. You’re going to feel like you’re ready to start training, you’re going to contact me and say, Trevor, I know that you told me to recover for a week but I’m feeling ready to train. And when you are thinking about emailing me or calling me to tell me that what I can tell you is you are not recovered. As a matter of fact, your body hasn’t even started the true recovery mode. We’ve talked about this before, your body has natural painkillers. And when you’re really beating your body up, it’s going to get those painkillers flowing. So and when you are really fatigued, you did a hard block or a race, yeah, you’re aware that you’re tired, but at the same time, you kind of feel good. And it’s hard for your body to recover when those painkillers are flowing. So there’s always a point on that recovery week where my – I will get the email I want for my athlete, which is I woke up this morning and I feel like I got hit by a bus, I could barely get out of bed. That’s to me is when the proper recovery has started. And a true recovery week – I don’t want my athlete coming out of it feeling great. I actually want them coming out of it feeling really flat. Recovery weeks actually aren’t a lot of fun. And then we start back up with the training. And after a certain length of time of training, that’s when they start feeling good again. How long that takes, again, is incredibly variable. And it can vary from person to person but even for an individual, it can that length, what your body needs can vary quite dramatically. I have had times where I’ve been beat up and I go through that whole cycle and I’m ready to train within four or five days. I’ve had times where it’s taken me two weeks before I feel like I’m really ready to train again. So my first suggestion is if you are going to do this, if you are going to take a true recovery week, don’t do this right before a big event. Because it could be a long time before you’re really ready to fly again. You know, it might be, yeah, you you go through that whole cycle like I do sometimes in four days and you feel great and you’re ready to go. Your power numbers are up and fantastic. But for example an athlete I was coaching last year, he was having really good spring, form was great. He had to take a trip to England for a friend’s wedding, and took a week off the bike and came back. hopped into a race a few days later, got popped almost instantly, felt lousy – it was three, four weeks before we had him back to racing form. So you just don’t know.

Chris Case 40:20

What are some tools that people can use – or in this case, Ben is looking for a way to really understand and he’s mentioned Whoop. And we have experienced with Whoop, what can you tell us about that product and what is it trying to indicate to the –

Trevor Connor 40:35

Heart rate variability can be a really good guide and we have talked about this before. And they’ve even done studies where they’ve used heart rate variability to direct people’s training as opposed to a periodized training plan and show that the people who are using heart rate variability to define their their training day to day and week to week actually saw greater gains. So that goes back to that whole back in the 80s, and 90s, these teams like the German national team, I believe, where they had doctors that were checking them every morning and literally telling them day by day, what they should be doing further training, heart rate variability and the Whoop strap, which uses heart rate variability with along with a couple other metrics can be really effective at that. Important thing, when you’re looking at heart rate variability is not to get too caught up in an individual day, heart rate variability as much more effective if it’s averaged out over a week. And the Whoop strap again, does that so when it’s giving you a recovery score for a day, it’s doing a running average – so it’s not just your heart rate variability that morning. All this being said, I have several my athletes using a Whoop strap, I’ve used one myself, these true recovery weeks are where the Whoop strap can actually fool you a little bit. And there’s actually even a white paper on the Whoops website that addresses this – that in higher level athletes, you can get what’s called parasympathetic saturation. And the short version of this is, while you’re in – what I what I see with my athletes, when this happens is when they are doing a training camp that is fatiguing them, their their recovery score on the Whoop is actually going up. And then on the recovery week, once they hit that point where they they get hit by the bus, and they’re actually starting to recover, their Whoop score tanks. So your Whoop score is actually the exact opposite of what’s going on.

Chris Case 42:53

Now bringing this back to the theme of this week, TSS. He mentioned having his TSS – that doesn’t seem to be obviously depends on what you’re you’re averaging overall, or what your big weeks look like -ut that doesn’t seem to be nearly nearly low enough.

Trevor Connor 43:12

And thank you for bringing that up – I don’t generally use TSS as a guide for recovery. I really go more with the sensations of what I’m looking for in my athletes. And during a recovery week, I will tell my athletes call me every single day. Let me know how you’re feeling. We’ll do test rides and I want to know how they’re feeling. And it’s much more based on sensations. But in terms of if you are measuring the TSS, so you’re right, Ben said he cuts it down, he cuts his weekly TSS in half. To me, that’s a sign that he is not doing a true recovery week. So to give you an example, my typical week, my TSS will be 600 to 800. When I do a training camp week, my TSS will be closer to 1200. On a recovery week, I don’t want to break 150. So you really, really want to recover and I see athletes really struggle with that. So I did a recovery week in February, where I finished my camp on Sunday, I didn’t touch my bike until Friday. Friday was an easy spin, Saturday was an easy spin. Then Sunday was just a three and a half hour long, really slow ride. And even that might have been a little too much. But when I tell athletes to do that you just see the nervousness of “but I’m going to detrain, you know, I can’t go that long without riding the bike” – but if you’re trying to do proper true recovery, you got to do that sometimes. Yeah, it’s really interesting to see that so many athletes have a lot of determination when it comes to getting their numbers super high. If they could also take that same determination and strategically use it to make their numbers really low, sometimes they might actually benefit from that. When I was coaching the Morning Glory cycling club up in Toronto, I would see this every year and I really tried to warn the athletes about this. They had a camp at the end of April, beginning ofMay – can’t remember exact dates down in Boone, North Carolina. That was four days. So it was Thursday through Sunday. And it was brutal, I mean, it was six hours plus every day where we were just going in throttling each other up every climb and in North Carolina, and you are just smashed by the end of it. I came back from that and I did my recovery week. I barely touched my bike the week after that. I saw several of the people who went to Boone, North Carolina, you know, we had the talk. The people running the camp said you need to make sure next week is a recovery week and they went Oh yeah, we get it. Well, the club had a Tuesday morning training race and the Thursday morning training race. And half of these guys would be at both training races, racing them.

Chris Case 46:14

Recipe for disaster.

Trevor Connor 46:16

And I’d ask them and they go, well, but I didn’t ride on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, or I went for easy spins on Monday, Wednesday and Friday so that was a recovery week, right? And you just go No. And I would see some of these guys who would do that, the rest of the season, they would actually be racing worse after Boone than they were before Boone because I think that camp combined with not doing a proper recovery week after was what flipped them over into overtraining. And they just never got out of it after that.

Chris Case 46:49

Would you say that if you’re training camp weeks, or these blocks that you do get bigger, that consequently the recovery weeks are that much more critical to get right?

Trevor Connor 47:06

Yes, I would say the the more a camp destroys you, the more you have to be really careful about doing the recovery right. But what is the right amount of recovery? That’s where you really have to listen to your body and let it tell you. I get asked again and again and again by athletes, so what I need six days for this one, seven days for this one? And my answer is always your body will tell you.

Chris Case 47:34

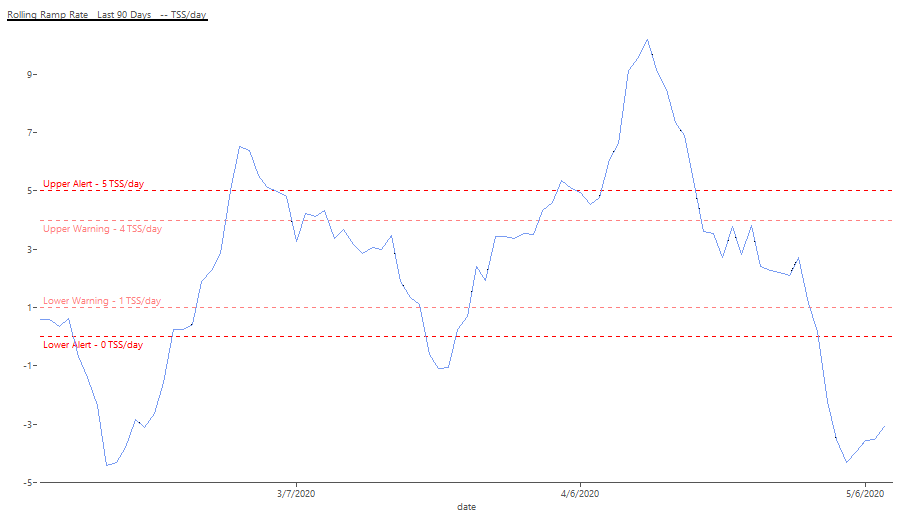

Yeah, it all depends. Last but not least, let’s take a question from Twitter. This is from Alfredo. His handle is AlPeralta_C if anyone out there wants to retweet him or tweet back at him, or do some tweeting of some other kind – I don’t know. Twitter, Twitter’s crazy, crazy world. All right. His question is, what would be a manageable weekly CTL ramp rate without generating too much fatigue? Trevor, I know you have some great thoughts on CTL, TSS, in general, what do you think?

Trevor Connor 48:14

Well, first of all, great question and really appreciate this, because this is a question in response to a very recent episode, where we address questions about CTL and TSS and all those metrics. So I will start by just reminding what I said in those episodes, which is my bias. I think there’s value to CTL but I don’t live or die by it as a coach. There are coaches out there who do live and die by it. They live on these metrics and quite frankly, they might be the better ones to answer these questions than me, because I will go into this. And there is a graph in WKO showing your ramp rate and it has its suggestions on what’s appropriate ramp rates. That’s not how I coach.

Chris Case 49:07

So you say it’s available in WKO? Is it also available in just the – No, it’s not. Okay.

Trevor Connor 49:15

So why don’t we talk a little bit about that graph – which – do we want to post this?

Chris Case 49:24

Yeah, we can. Yeah, we can post it.

Trevor Connor 49:27

Yeah. So I’ll show you mine. Just because I get a good laugh out of it. It has a suggested range for a ramp rate. And the one thing that’s fairly consistent about my training as I’m either above or below the suggested range, but almost never in it.

Chris Case 49:43

Well, that – you being a nonconformist that fits with everything that you do in life basically so much yeah.

Trevor Connor 49:51

So remember that CTL is a weighted average of your daily TSS, so the simplified version, if you have a, if your CTL is at 100, that means over the – and let’s say you’ve set your graph to a 42 day running weighted average, that means for the last 42 days, you’ve effectively been averaging 100 C – 100 TSS per day. So the ramp rate is how much TSS you want that to increase by per day. And the graph in WKO suggests that the ideal range is one to four TSS per day, and then has a alert range, that’s zero to five. So if you’re above five or below zero, you’re not training effectively. And I’m just looking I hit 10, a couple of weeks ago. And then I dropped down to negative five the following week.

Chris Case 51:00

Mm hmm.

Trevor Connor 51:01

So apparently, I’m not liking that range. So that’s the idea behind it. They’re basically saying this is the ideal range, I do have this graph, I do look at it. I have some athletes where Yes, they seem to when they when they are within the that range, they seem to be progressing very well. With other athletes, no, that doesn’t seem to be right, I know what’s right for me. And you’ll see when we post mine, I am rarely within that range of I’m above or below, because I’m that type of athlete, I like a training camp approach, I like to have a big fatigue week and then recover, then build up to another big fatigue week, then recover. That’s the best training for me. And that puts you either above or below the ideal range. So what is ideal, highly, highly individual. And I don’t think it’s as simple as saying, here’s a, here’s a metric. This is what’s right for everybody, you have to find what’s right for you, you have to find how you respond and I think you need to move beyond the metrics. And this is where you really need to know your own body and how you’re feeling. So for example, if you are looking at this graph, and you’re sitting between that one and four that they’re recommending, but you’re waking up every morning, dragging your feet, you’re struggling to do your intervals, you can’t look at the graph and go, but I’m in the ideal range. No, you’re fatiguing, I think it’s more valuable to look at your CTL, know most athletes have a CTL where they tend to perform best for some athletes it’s 8, for some athletes asyou get into pros is up around 140, you need to know about what’s the right CTL for you, where you perform your best and target being at that CTL when you want to be performing at your best. And then I would say it’s – if your ideals 100 and you’re at 50 three weeks before that you try to ramp yourself up, you’re in trouble

Chris Case 53:04

That is too steep of a ramp rate, right?

Trevor Connor 53:06

So you want to plan it out so that you’re doing something reasonable to get there. What is reasonable in terms of the way I would look at it, in terms of knowing your body? If every week you are fatigued and struggling, you are training too hard, and you’re going to get yourself in trouble. Conversely, if you never have weeks where you’re fatigued, you’re probably not training hard enough. Probably not pushing yourself – so with my athletes, I look to have standard weeks where they go yeah, that was hard, but it was very manageable, I could keep that up. But you want periodic weeks, where you go, that was tough, I pushed myself, I am tired, I now need rest. That’s more how I look at it is that balance of weeks that are easier, weeks that are much harder that are fatiguing, and some weeks that are fairly standard manageable. And whatever that ramp rate is, is whatever that ramp rate is.

Chris Case 54:05

I really can’t see why you didn’t answer this question on Twitter. I mean, that was like 140 characters right there.

Trevor Connor 54:11

Good point. What would what would be the short Twitter version of that?

Chris Case 54:17

You think about that. and post it. I don’t – I don’t think we have the the wherewithal to do that right now, after all that was just said.

Trevor Connor 54:26

Ah, maybe they’re really simple Twitter responses to put my graph up and just say not this.

Chris Case 54:32

Not this. There you go. That’s even even shorter. Don’t do what Trevor does, do what he says, not what he does.

Trevor Connor 54:40

This is pretty much we could summarize – if we wanted to summarize our entire podcast on Twitter, it’d be pretty much just post a link to my training and go don’t do this.

Chris Case 54:52

Don’t tell people that. But like I said, do what he says, not what he does because I have ridden and trained Whichever, and he breaks his own rules a lot of the time, don’t you?

Trevor Connor 55:03

Well, the rule that I follow that is true for every athlete is every athlete is unique.

Chris Case 55:10

Mm hmm. Especially you.

Trevor Connor 55:11

And you have to find what works for each individual athlete. And I have found what works for me. And I will tell you right now, and I don’t see this as a – being hypocritical – I give very few of my athletes what I do.

Chris Case 55:30

Yeah, that makes total sense, right.

Trevor Connor 55:32

And I actually made that mistake very early as a coach, I gave several athletes, basically the, my training template, and they all suffered for it. And very quickly learned, don’t give them what I do. This is right for me. It’s not right for them. And it’s about finding what’s right for each individual. That’s probably the full swing back to what’s the right ramp rate. Well, what’s the right ramp rate for me versus what’s the right ramp rate for you versus Chris versus Jana? By the way, Janet climbed up into the mountains for the first time this weekend –

Chris Case 56:10

And she froze her butt off. She needs new clothes. Hey, clothing companies out there send Jana some clothing, she’ll test it out for you, give you great reviews. She has – it’ll be an improvement over whatever she’s wearing now.

Trevor Connor 56:23

Jana did with all athletes who are new to cycling in Colorado did and dress for the weather in Boulder and then went up in the mountains on discovered it’s much colder up there.

Chris Case 56:35

Mm hmm.

Trevor Connor 56:38

Anyway, the point being ramp rate should be individual, you have to find what’s right for you.

Chris Case 56:44

Yeah, it’s exactly why you know, when we get a pro on here, or if we get somebody, any anybody, really. And we ask them Oh, so how do you train? Or what’s your workout like? It doesn’t really, it doesn’t really matter when you look at it from that point of view, because you don’t want to copy what a pro does, you’re not a pro, even if you’re at that level, pros train differently. Pros train to their own physiology, to their own preferences to their own situations and so forth. So just copying somebody’s training plan, It’s not – it can get you somewhere, but it doesn’t get you to the best place.

Trevor Connor 57:22

Right? What do you have to do is listen to all these different ideas and this is why we actually have so many side interviews, with pros, with a lot of different people that are going to give you different opinions, because what you have to do is listen to all these different things, try the different things for you. Again, going with that ramp rate and one of the reasons I don’t give athletes what works for me, I’ll give you two examples. I have one athlete who I train, who in the winter, I can hit him really hard, and push him really hard. But when we get into the season, if I give him hard weeks, he very quickly goes over the edge and can’t race well. So we get to the race season, I really need to back down his training to where almost the only intensity he does is races. And then he performs at his best. We are joking about me, part of the reason I don’t give any of my athletes what I do is what is best for me is when I’m coming up on a target race, I do two, three weeks of tearing myself apart. At some point in the middle of that two to three weeks, I hit a point where it feels like I am getting dangerously close to an overreach that I would immediately pull one of my athletes back from, for some reason, I pushed through that and then all of a sudden, I just come through the other side. And I’m performing at my best. And like I said, early in my coaching days I went Oh, that’s the way it works so I did that with a bunch of athletes and they never came through the other side.

Chris Case 58:56

Yeah. And you don’t work with those athletes anymore.

Trevor Connor 58:59

One did fire me, rightfully so. The rest I adjusted.

Chris Case 59:03

Yeah. But it probably took you a long time too to realize what worked for you, took some trial and error, took some experimentation. That’s sort of the the point here too, is that you can’t just take what we tell you to do, and expect it to always work for you. You have to interpret that, you have to go out try it. If it isn’t right, well, we’re not necessarily wrong. It’s just that the advice we gave wasn’t perfect for you. So you have to modify from there.

Trevor Connor 59:30

There are certain principles that we believe in that apply to everybody. That’s why I keep bringing up the fundamental principle – the one thing that’s true of everybody, you need to stress your body at a level that it can’t handle.

Chris Case 59:44

To come back stronger, to make it come back stronger.

Trevor Connor 59:46

To hyper compensate. And how you get there – there’s a lot of different ways, but if you’re never really stressing your body, you’re never gonna get stronger.

Chris Case 59:54

You’re just gonna stay at the same level.

Trevor Connor 59:56

Right and for some people, you actually say this is unfortunate about me, it’s a hell of a lot of stress before my body rebounds. For other people, it’s not a lot of stress. Hit themselves hard for a couple days, take some rest and all of a sudden they’re flying. So you need to find what’s the right balance for you. And it is individual. The software helps. But get away from thinking everybody’s graph needs to look same.

Chris Case 1:00:28

That was another episode of Fast Talk. As always, love your feedback. Email us at fasttalk@fastlabs.com. Subscribe to Fast Talk wherever you prefer to get your podcasts. Make sure to leave us a rating and a comment. Become a fan of Fast Talk on our social media channels. Our handle is @realfastlabs. The thoughts and opinions expressed on Fast Talk are those of the individual. For Coach Trevor Connor, I’m not-coach Chris Case. Thanks for listening.