We review four recent studies from the scientific literature, addressing the hypotheses, methods, and conclusions of each to give you a greater understanding of the latest findings in endurance research.

Episode Transcript

Chris Case 00:11

Everyone, welcome to another episode of Fast Talk your source for the science of endurance performance. I am Chris Case, sitting down today with Trevor Connor, and we’re going to try something a little bit new for Fast Talk today. We’ve dubbed it Nerd Lab. You’ve heard us refer to each other as nerds before on the show, this is when we get really nerdy and we pick apart some studies that we’ve liked, something new, we tend to do something similar on some shows, but we don’t go very deep. We sat down not too long ago with Dr. Stephen Cheung, someone you’ve probably heard before on Fast Talk, and hopefully you’ve seen a lot of his great content on Fast Talk Laboratories website, his workshops, and, and other things. He is a professor from Brock University, you’re going to hear from him, and he reads, lots and lots and lots of papers as an editor for some journals as well. So we pick all of these things apart. Trevor, I know you were really excited about this Nerd Labs concept, because you kind of do this for fun, for entertainment all the time.

Trevor Connor 01:20

This is my answer to the question, if you were sitting on a beach with nothing to do, what is the best thing you could possibly do with your time and for me, it’s, yeah, I’d sit on a beach and read research.

Chris Case 01:30

And I think that is actually the definition of a nerd, somebody who goes to the beach to read studies.

Trevor Connor 01:36

I always picture, I think I’ve told this story before, but my dad who loves to read research in business in the finance world, he was literally sitting on a beach at a friend’s cottage, and their eight-year-old son came up to him and said, “What are you doing?” My dad’s like, “reading research.” Like, “why are you doing that?” My dad gave him this whole thing about well, “when you go to the beach, don’t you want to do the thing you enjoy most in the world? This is what I enjoy doing.” Thinking it will get through to the kid, the kid just looks at him and goes, “You’re weird.”

Chris Case 02:08

I can see you sitting on the beach with your swim trunks, a pocket protector, no shirt on, just the pocket protector somehow on your chest.

Trevor Connor 02:16

Ouch.

Chris Case 02:16

Well yeah it might hurt with some pens, and nerdy glasses with the little scotch tape holding them together in the middle, and you know a pile of, well you don’t use paper, a digital device with some, that’s not as fun, I want the papers surrounding you on the beach.

Trevor Connor 02:35

It would be a ton of paper.

Chris Case 02:36

Blowing in the wind, you know, you’re going into the surf to try to get Dr. Sieler’s latest publication in nature or whatever it is.

Trevor Connor 02:44

My issue with this, I have never used a pocket protector.

Chris Case 02:47

Ah, damn.

Trevor Connor 02:48

I don’t wear glasses, otherwise everything is 100% accurate.

Chris Case 02:52

Okay, swim trunks and research literature.

Trevor Connor 02:57

And I have done this.

Chris Case 02:59

I’m sure you have.

Trevor Connor 03:00

When I go to Tobago, I sit there on the beach, and read research.

Dr. Stephen Seiler 03:06

Hey, I’m Dr. Stephen Seiler, of the University of Agder in Norway, and I’m a longtime contributor to and a fan of, Fast Talk, and now Fast Talk Labs. I’m really happy to be involved, I think, Fast Talk Labs with Chris and Trevor and their team, exemplify some aspects of the coaching and the process that I value. One is science and being evidence based, but another is communication. Communication between coach and athlete, communication between coach and other coaches. And then finally trust, building trust in that communication, in that forum where everyone wants to learn and work together to be better. And I really believe that’s what you’ll find with Fast Talk Labs, so I’m proud to be part of it, and I hope you will enjoy it.

Trevor Connor 03:58

That was Dr. Seiler from Fast Talk Episode 139, when we introduced Fast Talk Laboratories and our new Virtual Performance Center. If you enjoy Dr. Seiler’s appearances on our show, we have really good news for you, we just unlocked all 40 of Dr. Seiler’s webinars, lectures, and interviews on our website fasttalklabs.com. They are now free for members, join at fasttalklabs.com, and you can get Dr. Seiler’s pioneering work in one convenient place. Sign up for a free listener membership today, at fasttalklabs.com.

Trevor Connor 04:35

Important to point out, yes this is a second recording, there is a reason behind this. You take four of us who love reading research, you put us in a room together and we don’t leave. There was a certain point where Jana had passed out from probably boredom, and we were still talking. We are going to give you the trimmed up and hopefully higher energy, more exciting version of some new research.

Chris Case 05:02

Not the cliff notes, you might call them the Trevor notes, the Connor notes.

Trevor Connor 05:06

Sure, I’ll go with that.

Chris Case 05:07

Yes. Great.

Trevor Connor 05:08

Beach notes?

Chris Case 05:09

Beach notes, the beach notes of science.

Effects of Time of Day on Pacing in a 4-km Time Trial in Trained Cyclists

Chris Case 05:11

All right, this first study comes from Dr. Stephen Cheung, he selected it. It’s called, “Effects of Time of Day on Pacing in a 4-km Time Trial in Trained Cyclists” coming from the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, came out in 2020. Trevor, what was the overriding theme here in this study?

Trevor Connor 05:34

Pretty simple one to this study, but something I actually really like, because I enjoy talking with my athletes and saying, “You’re not always going to feel your best in race day, sometimes you’re going to go and you’re going to feel pretty bad, but you’d be amazed at your ability to perform your best.” And I think this study is an example of this. So they had athletes perform this time trial at different times a day, to see the circadian rhythm impact on performance, and basically said, there is none. They did virtually the same time, anytime of the day. So there isn’t too much more to it than that, that’s the message, you might have times of the day you feel better.

Chris Case 06:19

Right, right. There could be a preference here, but in terms of the science and the data, it will suggest that it doesn’t really matter, Morning, noon or night.

Trevor Connor 06:29

You’re gonna be your best.

Chris Case 06:30

Yeah, exactly.

Trevor Connor 06:31

So the way they did this was, they had the athletes come in, not all on the same day, but repeat this time trial over multiple, multiple days, all the way from 8:30 in the morning, to 8:30 at night, to see the impact. And like I said, I think the time difference between their slowest than their fastest was something like four seconds, it was pretty tiny.

Chris Case 06:58

And not significant.

Time of Day Does not Effect Time Trial Performance

Trevor Connor 06:59

None of it was significant. The only thing that actually showed any significance in this study, which you would expect, because we’ve seen this as part of the circadian rhythm, is body temperature. We saw that their body temperature was lower in the morning, at its highest kind of mid-afternoon. So that was one of the reasons they wanted to conduct the study, they thought, if your body temperatures higher, you’re probably going to perform better, so they were expecting a better performance in the afternoon, but they just didn’t see that.

Chris Case 07:27

Great. Let’s hear what Dr. Stephen Cheung had to say about this paper.

Dr. Stephen Cheung 07:33

I know for me, I’m generally either a, not early, early, morning exerciser, I’m not the one to wake up at six o’clock to train, although I will if I’m absolutely forced to, but you know, I generally prefer morning or maybe kind of early afternoon, I find evening, kind of afternoon evening kind of after work exercise really tough me because I’m either hungry, or, you know, or if I’ve eaten, then I’d feel really sluggish. So, yeah, it’s, I think a study like this also has practical outcomes for a lot of lot of professional athletes to, who their peak performance, set by TV schedules is an evening and, you know, to, to be able to adjust their, their clocks and their patterns and just have that really daily rhythm so that you’re really in sync so that you know, at 8:30 you’re ready to go, and that is your set schedule. Do your exercise, do workout whenever it suits you best, don’t let it be a mental crutch at all, you know, I, I I have, I can only do it today at lunch and that maybe that’s not my best time of day, just go in knowing that you can still perform, and you can still get the best outcome.

Effects of Different Goal Orientations and Virtual Opponents Performance Level on Pacing Strategy and Performance in Cycling Time Trials

Chris Case 09:03

All right, well, let’s move on to this next study that actually dovetails quite nicely with the previous one, It has to do with time trials. Trevor you selected it, “Effects of Different Goal Orientations and Virtual Opponents Performance Level on Pacing Strategy and Performance in Cycling Time Trials.” That’s a mouthful, it comes from the European Journal of Sport Science. You actually, look at this, it came out ahead of print and you stole this from the library, It’s not even published yet. How’d you do that?

Trevor Connor 09:35

Well, I went there late at night, dressed completely in black.

Chris Case 09:41

Pocket protector?

Trevor Connor 09:42

Yes.

Chris Case 09:43

Yeah. Good.

Trevor Connor 09:44

With the multi-color, that almost gave me away. I almost got caught.

Chris Case 09:47

Tell us a little bit about this study, Trevor.

Trevor Connor 09:50

So really, for me, two big take homes or messages from this study. First one was about pacing. So I’ll go into the methodology in a minute, but basically they had these athletes time trial solo, and then time trial against a virtual partner. What they found, as you would expect, is pacing strategies were very different, depending on whether they’re racing solo, or whether racing against this virtual partner, in a virtual time trial. So the time trial solo, you saw them start out easier, kind of maintain their pace in the middle section, and then really push it in that last kilometer, and so it was a 10k time trial, really pushing in that last kilometer for the finish. When they were racing against a virtual partner, they went out much hotter, much harder, and that that first bit, so the first kilometer or two, then settled, again into kind of that regular pace, but they did not push the end. Simply because, by the time they were getting to the end, they were either certain they were going to win it, or certain they were going to lose it.

Chris Case 11:02

So there were two different conditions, there was a slow opponent, quote, unquote, and he was or she was 3%, slower. And then there was a fast opponent, and that person, or that virtual opponent was 6% faster.

Trevor Connor 11:20

Yeah, this was kinda the cool part about the study, so they had them repeat this 10k time trial four times, first two times or solo, they took their best time for the solo effort, and as you said, they then created a virtual partner that was 3% slower than their best effort, so they knew that you could beat that person, and then the virtual partner that was 6% faster, so they knew there was no chance of you beating it. So they want a scenario where you were going to lose, and a scenario where you were going to win.

Chris Case 11:46

But the participants, the subjects, didn’t know that.

Self-efficacy

Trevor Connor 11:50

No, they were being told that they were racing against other subjects in the study. So this gets into the second big message of the study, and this was what really surprised us, and I still don’t know how to interpret this. What they are looking at or trying to look at was self-efficacy, this is your sense of your belief in your ability to perform the task. So they wanted to see how having racing against somebody affects your self-efficacy, the idea being, if you’re beating somebody that’s probably going to improve yourself efficacy, if you are losing, that’s probably going to reduce yourself efficacy. And sure enough, in this scenario, you are racing against a virtual partner, you could not beat, self-efficacy plummeted. They had a, you know, that’s a different conversation, but they had a way of measuring every minute during the time trial, your sense of self efficacy. So it plummeted. And I think they even theorized that one self-efficacy plummeted, your performance was going to drop. Here is what was surprising, the difference in the times was not significant, basically, it was the same time in all three scenarios going solo, raising against a slower opponent, racing against a faster opponent, and that was surprising because the thought was, you would probably be faster going against the slow opponent, because that’s very motivating, and you put in your slowest time versus the,

Chris Case 13:13

Right.

Trevor Connor 13:14

The much faster opponent, now that, you do see that in the results, but we’re talking a couple seconds here or there, which wasn’t significant, but there was a slight difference.

Chris Case 13:23

It’s Yeah, it’s that carrot or stick as motivator, which would work better for an individual athlete in this study is basically saying neither Is that true?

Trevor Connor 13:34

Pretty much. They’re certainly saying they didn’t see a significant difference. So that we’re talking so I mean, the solo was average time was 13.05, going against the slower opponent was 13.01, and going against the faster opponent was 13.11. So slight differences, but really, really pretty minor. So not sure how to interpret that, I think the key messages here, for certain racing against an opponent is going to affect how you race, how you pace yourself, so that’s an important thing to know. I do kinda like the message that even if self-efficacy drops, even if you’re against somebody who is faster than you, you still might be able to put out a good performance and you should probably just keep your head down and keep going.

Chris Case 14:24

That is a good message, definitely. This is a race against yourself, not against other people, essentially.

Trevor Connor 14:30

But also important to point out that this does go in the face of a lot of the other research that’s out there, that has shown on self-efficacy drops, you tend to perform worse.

Chris Case 14:42

Hmm, interesting. Well, let’s hear from Dr. Cheung on this.

Dr. Stephen Cheung 14:50

I think it also really speaks to the power of goal, and the whole idea of racing against someone versus, versus time trialing and where it’s really kind of that intrinsic internal motivation is amazing. Certainly in time trials, if you get passed by the guy a minute behind you, unless you’re pretty mentally strong, that can be a whole cause for just cracking and saying, “Okay, well, that’s it. If I’ve been past, what’s the point?” And, yeah, it just really speaks to that, that power of that goal, as long as you still think it is achievable, it can be such a strong driver, but the second that it becomes absolutely evident that it is not achievable, your self efficacy, motivation, you just take its massive, massive hit. So I think it really speaks to in some senses, the, this, the importance of setting goals, and setting the goals that are proper, that are going to stretch you but aren’t, in a sense, so completely unrealistic. So I think it has that analogy to the podcast that you had about kind of what is a good goal? And how to go about setting it. So I think it has that, that nice extrapolation to there.

Health Consequences of an Elite Sporting Career: Long-Term Detriment or Long-Term Gain? A Meta-Analysis of 165,000 Former Athletes

Chris Case 16:14

Alright, let’s move on to our next paper, selected by Dr. Stephen Cheung, It’s entitled, “Health Consequences of an Elite Sporting Career: Long-Term Detriment or Long-Term Gain? A Meta-Analysis of 165,000 Former Athletes”, this ran in Sports Medicine, actually came out in 2021, so hot off the presses. Trevor, this is an interesting one, and with a bit of a simple conclusion, honestly.

Trevor Connor 16:45

Yeah, I mean, good conclusion, for us.

Chris Case 16:48

Absolutely. We chose a good sport.

Trevor Connor 16:50

But a pretty simple one, so this was addressing this whole notion that’s been coming out of this j-shaped curve relationship, between physical fitness and all-cause mortality. Meaning, if you are completely sedentary, yes, this is absolutely been established, that is going to increase your risk of all-cause mortality, so it’s going to reduce your longevity. But the question is, whether it’s then a straight line with fitness, or whether it’s as j-shaped, where at a certain point, if you’re training so hard, and so much, it actually once again, increases your risk of death, or reduces your longevity. So they wanted to explore this, it is a meta-analysis, love meta-analysis, because you can never really draw a conclusion from a single study. So a meta-analysis is a study of many studies, where you take the highest quality studies on the particular subject out there, and then there’s very sophisticated statistics that can pull all their results together to come up with a overall result.

Chris Case 17:59

Pulling the data and giving it more strength, in a sense, right?

Trevor Connor 18:02

So my old advisor used to say that meta-analysis are the highest quality study out there, and ultimately, you can’t truly prove something until there is a meta-analysis to demonstrate it. So this is the meta-analysis and what they found after studying, how many?

Chris Case 18:20

165,000.

Trevor Connor 18:21

Thank you. Yeah, it was right there in the title. Thank you very much.

Chris Case 18:25

You’re very welcome.

Trevor Connor 18:26

Yes. So after studying 165,000 former athletes, no, it’s a straight line relationship is basically what they found, you aren’t really seeing that j-shaped. A couple interesting things to point out when they fine tune it, one, that you see a decrease in CVD mortality in endurance athletes, not in power athletes. So since I’ve just been informed I miss pronounced success, I don’t put the suck in it, I’m just gonna say suck it, power athletes.

Chris Case 19:01

Wow. Throwing it down, picking a fight with the wrong people I would say.

Trevor Connor 19:05

Yeah, they can pretty much beat me up. If they can catch me.

Chris Case 19:07

Yeah. With their pinky fingers, they could take you out.

Trevor Connor 19:10

Yeah, that’s pretty much true, so I take that back. Cancer mortality was not lower in endurance athletes, but was in some of the other athletes, and then the other unfortunate thing, which I think we’ll hear a little more about from Dr. Cheung, is the fact that they couldn’t find enough research specifically on women, to draw similar conclusions about women.

Chris Case 19:34

Let’s hear from Dr. Cheung now.

Looking at Anecdotal Cases

Dr. Stephen Cheung 19:38

The focus on cardiovascular disease and cancer is because those are two of the biggest contributors to all sorts of mortality. Those are the two big killers in the world, so by tackling those two, they got they got kind of the two big whammies in a sense, and then in terms of what else could they have looked at, again, unfortunately, the data just really isn’t there for, for females, they, even though they had decent sample size, they had 15% of 165,000, is still over 20,000, but they note of that it was really from two studies have one of which was large, and the other was really small. So, so they couldn’t really draw good data from there, because there just wasn’t the number of studies, so that’s really unfortunate. It points out a glaring lack of researching female physiology and health and in an exercise that needs to be addressed. And but I think, again, I’ve done a lot of meta-analyses in my own career on different topics, and it is a very powerful tool. And yeah, so I, I overall, like this study, I think it was well done. And the big take home message, I think, is not to look at these anecdotal cases, right? Because we hear of Jim Fixx, the runner who started the whole running craze, he died from a heart attack at age 51, and you hear of a story like that, and you think, “Oh my God, maybe I shouldn’t be exercising or shouldn’t be exercising that hard. Look what happened to Jim Fixx.” But what a study like balances out by saying that just one case, that’s one kind of high-profile case, that in the sense is, is almost an outlier. If you take overall percentages, and just like in baseball, you play on probabilities, you are better off the percentages are in your favor, actually, if you are active and exercising, so don’t just look at those, you know, one single really high-profile cases and, and base your, your ideas or on something on that one anecdote, really look at a percentage basis, and that’s what meta-analyses allow you to do.

Cardiorespiratory Responses to Constant and Varied-Load Interval Training Sessions

Chris Case 22:19

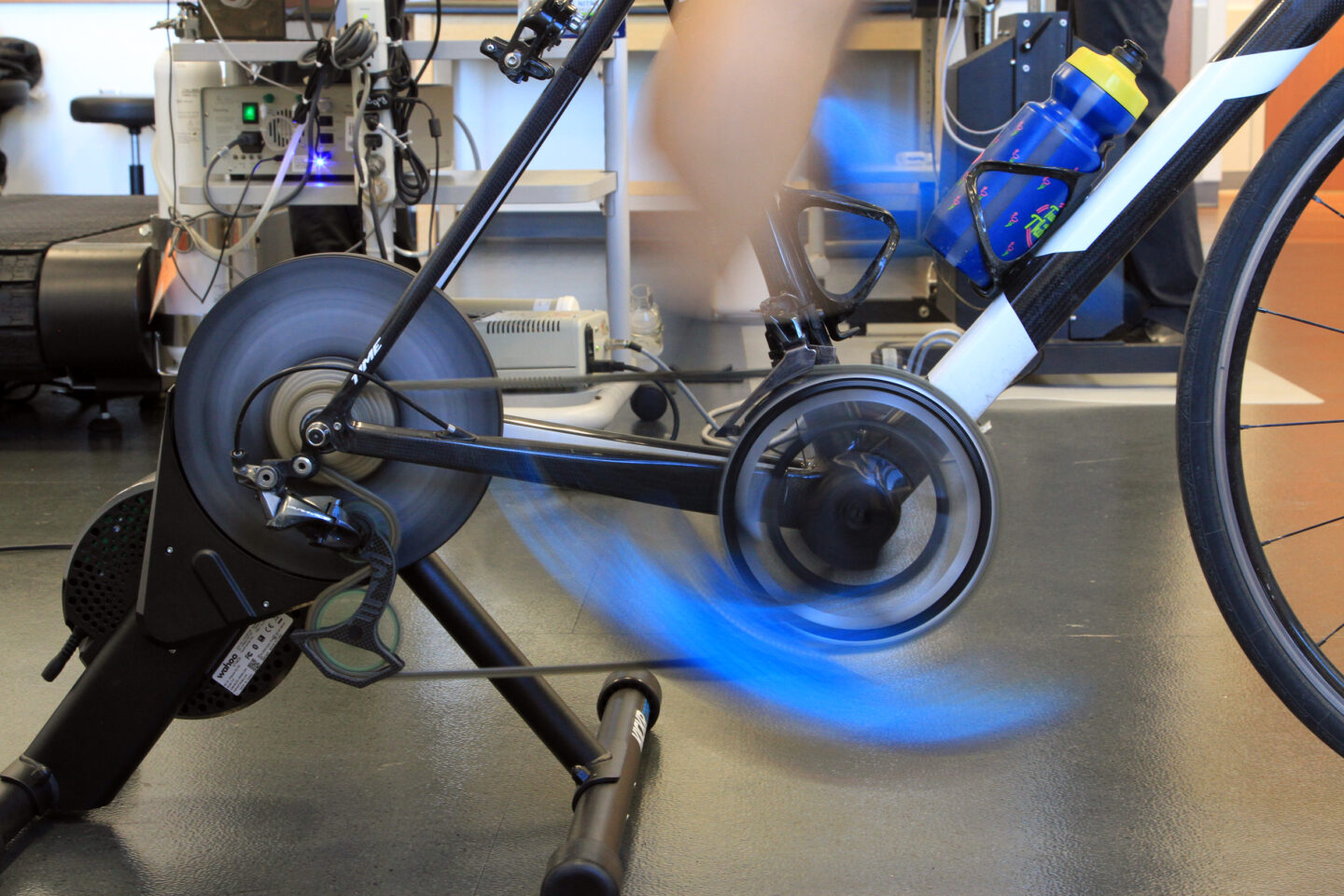

Alright, let’s move on to our next study, this one Trevor selected, “Cardiorespiratory Responses to Constant and Varied-Load Interval Training Sessions.” This comes out of The International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. Again, ahead of print, you’ve stolen this, 2021 is the publication date. So let’s talk about some intervals here. What did they do? And what did they look for in this study?

Trevor Connor 22:45

Yeah, first, I gotta say a bit of a struggle for me bringing this one to the the group, but actually quite enjoy this because you know, I am all about steady intervals. The gist of this study is that saying, actually doing intervals at a constant wattage might not be the most effective way to do intervals. But I always love reading research that makes me think, makes me adjust my beliefs about things. So I actually quite enjoyed this study. It was a pretty simple study, they use cyclists and runners, I’ll just talk about talk about the cyclists, but runners exact same protocol, except instead of using power they just used pace, but so I don’t keep going back and forth, I’ll just talk about the cyclists. And the gist of it is they had them repeat a set of intervals, four-by-four-minute intervals with three-minute recoveries, twice. In one protocol, just steady wattage, right, I think it was right around Vo2 Max power, across all four interval sessions. In the second protocol, this was their decreasing protocol, where you started each four minutes, about 40 watts above the power that they used in the steady protocol and finished about 40 watts below. So ultimately, you ended up averaging the same wattage, but intervals obviously looked very different. So you over the course of the four minutes, you’re getting easier, easier, and easier. The theory behind this is goes back to what we’ve talked about a lot before, which is in order to produce an adaptation, you have to produce stress. So they talk in a study about the effectiveness of an interval session is really based on how much physiological perturbation you produce, and this I’ve been seeing more and more in the recent research. And they’re big proponents of this basically saying the effectiveness of intervals come down to how much time you spend it greater than 90% of Vo2 Max. So that was their theory, and what they based this on, so everybody, when they did these intervals, they were hooked up to a metabolic cart and they measured their oxygen consumption, and what they found was in those decreasing intervals, because you were starting out so hard, you tend to spend more time at greater than 90% of Vo2 Max. So basically, their conclusion is these intervals are more effective.

Chris Case 25:08

Right.

Trevor Connor 25:10

That does assume you believe that that is the best measure of an interval session, I would argue it’s really interesting, but you do now need to do that study where you have athletes go and one group does the steady intervals, one group does the decrease in intervals for six to nine weeks, then truly see if it produces a greater gain.

Chris Case 25:33

Right, long-term effects of this could be very different. It’s interesting too, Dr. Cheung recently did a workshop for us where he dove into some of the other studies that he’s recently seen about this, this difference, potential difference in gains between steady state and variable load, or Fast Start, you might hear them described as fast start intervals as well. So here he is.

Starting with a Higher State of Fatigue, Athletes end up Doing More Work

Dr. Stephen Cheung 26:04

Yeah, absolutely. And this fits in very well with the studies that I was looking at in that workshop, where they were looking at dryland skate skiing, and doing the same idea of starting at a higher level, then tapering down, as opposed to a steady state interval, and I think it was also about that four to five minute roughly effort and they found very similar things, so this fits in exactly with what I saw in those previous studies, and this also fits in with my bias that because you’re starting out with a higher state of fatigue, you are actually ended up doing more work and doing more getting more stimulus as a as a result. So those are my personal preferred style of intervals anyways, so I really liked this study because it exactly matches my own bias.

Chris Case 27:09

That was another episode of Fast Talk. Subscribe to Fast Talk wherever you prefer to find your favorite podcast, be sure to leave us a rating and review. The thoughts and opinions expressed on Fast Talk are those of the individual. As always, we love your feedback, so please join the conversation at forums.fasttalklabs.com to discuss each and every episode of Fast Talk. Become a member of Fast Talk Laboratories at fasttalklabs.com/join and become a part of our education and coaching community. For Dr. Stephen Cheung and Trevor Connor. I’m Chris Case. Thanks for listening.