We examine the pros and cons of using chronic training load (CTL) as well as the ways it can take your endurance sports training off track.

Episode Transcript

Chris Case 00:12

Hey everyone, welcome to another episode of Fast Talk your source for the science of endurance performance. I’m your host Chris Case. CTL chronic training load. This metric has rapidly gained in popularity among endurance athletes, but how well understood is this complex metric. Today, we discussed the benefits of CTL. As well as the issues that can arise if too much stock is placed in this one number. CTL can tell you the general level you’re at. And more importantly, it can indicate trends in your training, and help direct your training plan. But is this little acronym quickly replacing that other acronym, FTP, as the metric of reference? Indeed, many people seem to think of it as an indication of how strong they are. They place ALL of their stock in this one metric, but should they? Are there any dangers to doing so? As always, today, we start by taking a step back and defining how CTL is calculated and what assumptions and estimates It is based on. Today, Trevor, and I discussed the good, the bad, and the ugly of CTL. Ultimately, we want to try and answer as many of the questions we’ve received about this metric as possible, and help illustrate why a focus on training principles, rather than any single number is much more effective for creating adaptations, and seeing gains, as we always do on our summary episodes. Today, we’ll hear from a world-class group of coaches, scientists, and athletes, including Tim Cusick, Larry Warbasse, Joe Friel, Dr. Stephen Seiler, Dr. Iñigo San Millan, Kendra Wenzel, and others. Let’s make you fast.

Trevor Connor 02:07

In all of sports, nutrition is one of the most confusing and controversial topics. That’s because everyone has an opinion. And it’s hard to tell fact from fat. Plus what works for one person may not work for you. Now Fast Talk Laboratories is shedding some light on the science of sports nutrition. In our new sports nutrition pathway, we take a deep dive into the science and practice of sports nutrition, to help you find what works for you. This pathway features experts like Dr. Asker Jeukendrup, Dr. Brian Carson, Dr. Tim Noakes, Dr. John Holly, Julie Young, and Ryan Kohler. They create a science-based framework that will show you how to think about sports nutrition in a new way. For sports nutrition pathways, the only guide you need to this complex topic. See more Fasttalklabs.com/pathways.

Chris Case 02:59

Trevor, I know you have a lot of thoughts here. Tell me a little bit more about where you want to take this episode and this discussion on CTL.

Trevor Connor 03:09

I’m going to kind of give away the ending of the episode first- this is a summary episode after all- And that’s there is a value to CTL. But I don’t think the value is the same sort of thing you saw with FTP where it’s the higher the number, the better and I got to drive my number up. And we have gotten questions from listeners being concerned about an injury or taking a little time off because their CTL is going to tank and then they’re not going to be at the same level. So you can see them using that as the- here’s the measure of me as an athlete in total. What really kind of opened my eyes is I have an athlete, I’m coaching, who went out with a group on a ride. And this was a group that used to drop him a lot. And all of a sudden he was beating them up at the end of it. I think three or four years ago, they immediately got what’s your FTP, man, you’re doing great. Instead, they just came up, they’re like, wow, you’re really strong. What’s your CTL? And they were guessing his CTL was like 110 120. And when he told them as CTL was 70 they wouldn’t believe him.

Chris Case 04:20

Yeah, it’s that number of reference now amongst amateur riders predominantly. People equate that number with how well you’re riding a bike, and it just doesn’t work, It’s not that simple. And it doesn’t work that way for everyone. And there’s a lot more nuance to it than that.

Trevor Connor 04:45

I think it’s gonna sound like we’re beating up on CTL in this episode, we’re not doing that. It’s a useful metric we’ll hear later in the episode from Tim Cusick, who’s the developer of WK05 which they are the people who- along With Dr. Coggins and Hunter Allen – developed this concept of CTL for cyclists. You’ll hear him say, you know, CTL has a lot of value, especially for a coach, using it as a measure of yourself is not that valuable. And that’s where we’re going to get negative is looking at that number and saying, Oh, I’m 110, I used to be 100. I’m a stronger cyclist now.

What Is CTL?

Chris Case 05:23

We often will start an episode defining the terms we’re talking about. And I think it’s very appropriate in this instance, to do the same. Because this is one of those metrics that has become popular. People tend to take some of the complexity out of these things. And I think we should start from the very beginning, and really dive into the true definition of CTL so it’s very clear what this actually is a measure of.

Trevor Connor 05:55

I’m going to start by saying, it’s actually going to take us a while to get to the definition of CTL because it is built on so many things. I think it’s really important to understand all those things that it’s built on to understand the nature of CTL itself. To get at what that number is all about. So where I’m going to start is- CTL stands for chronic training load- I am going to give a definition of load. I’m not going to give my own definition, I actually am looking at a study from 2014 called establishing the criterion validity and reliability of common methods for quantifying training load. And they have a definition of load that when you hear it, you’re gonna go well, that’s actually really, really simple. It is… physical training load can be described as the dose of training completed by an athlete during an exercise bout. So that’s a very acute load, that’s a single ride. Chronic training load, hence, the chronic refers to the accumulation of that load over time.

Chris Case 06:58

It does seem very simple.

Trevor Connor 07:00

Right? That’s it? It is just how much did you put on your body. Well, actually, I shouldn’t say that. It can mean how much did you put on your body over the course of that workout. So this is where you get into and I’m going to use their definitions. There’s external load and internal load. So external load is defined as a measure of training load independent of individual internal characteristics. In short, on the bike, that’s power. How much power is going into the bike? So if you’re putting 300 watts into the bike, it doesn’t say if you’re a pro putting in 300 watts, not too hard. If you’re a new cyclist,300 watts you might only survive there for a couple of seconds. It doesn’t say anything about how much that 300 watts is beating you up, it’s just saying you are put 300 watts into the bike. Internal load is the relative physiological stress imposed on the athlete. So this now gets into the are you dying at 300 watts or are you going fairly easy at 300 watts. So another way to think about this is – we actually had Tim on the show. And so again, you’re going to hear this in the quote from him. And I was good to use this later. But maybe we should use this right now. It’ll give away a little bit, but I think this is a good place to use it. We did an episode with Tim, where he talked about stress versus strain. So that’s getting at that internal and external load. And his key point was, stress is what’s going into the bike that’s the external load. Strain is what’s going into your body. And the really important point that he made, which we will get to again later is stress says nothing about adaptation.

Tim Cusick Explains The Traps Of Data Science

Tim Cusick 08:54

Well, personally, I think both acute and chronic training, load measurement is crucial to all your successful training strategies. It’s something that has to be part of it. Remember, I’m talking about measuring training load at the moment, I know we are going to get deeper into some definitions. But to answer that question, right for me, I always want to start with one overarching goal. As we have brought more and more data to endurance coaching to being an endurance athlete, you got to understand what is the role of data? What is the role of data science? You look at a bunch of data, and now you’re a data scientist because you get power, you get heart rate, you got all these things. So now you’re a data scientist. People think that all this data and the data science we apply is meant to give us some definitive answer. Oh, go train for 56 minutes at 282 watts, right? That’s not what it really is. Data science is decision science. So you’re collecting all this data so that you, the person making the decision, has more knowledge and you improve the odds of the success of the decisions you make. In this particular case, we’re talking about athletes success, their ability to achieve their goal, you know, to be on peak form when they want to be on peak form. To win their big race, whatever that might be. But you’re really talking about data, all this measurement of training load and other factors that are involved in that. It’s not a magic answer. There’s no one – I open to can of data and what popped out, like springboard snakes you know, -magic answers of what I should do. What happens when you look at all the data, it makes you more knowledgeable, and it allows you to make better decisions, which increases the odds of success. When you apply exercise stimuli to an athlete, the response,- physiology isn’t this neat, linear thing, right? – responses can be different sometimes predictable, sometimes not. So all you’re doing is using all this data, to make better decisions to improve the odds of success. So, therefore, when you’re talking about training load,- remember, my definitions had measurement and quantitative within there- you’re talking about the ability to use this measurement of training load, to improve your odds of success. So that’s always my overarching thing with all data, something that all data should utilize. When you start talking about training loads, specifically, you really are talking about the measurement of training stress. And the production of the resulting strain and adaptation. So really, when you think about the most quantitative training load metrics or measurements that are out there, they are a stress measurements because we can best and most easily understand that stress. I have a power meter, I’m doing 300 watts, I get, I get that is 300 watts. That’s the stress, I’m putting out I have a hard number that’s very trackable. When you get to strain, we don’t have a great system of measurement of strain right now. It isn’t out there, you have heart rate, you have HRV, you have some other factors. But no matter what, you’re still somewhat in the dark of the true strain, the athlete is going under. We’re getting better at that we’re rounding out information and data there more and more. The trouble that brings with training load, the challenge and where the art of coaching, using data to make better decisions is important is we can measure the stress pretty quantitatively like there’s an objective set of data. we’re starting to get our hands around strain a little bit better. But reality is we don’t have that hard quantitative piece of data. Therefore, stress plus strain equals adaptation, we really can’t nail adaptation. So when you start thinking about training load, we’re really trying to improve the odds by understanding what we’re applying. We are applying a certain amount of stress, that stress is going to have some relationship to fitness, some relationship to performance specificity, some relationship to how the athlete performs in a given event. But we don’t have that same hard measurement for strain. Really when we think about the adaptation it’s our best guess. We don’t have that way of predicting the adaptation. Now the athlete goes to their event and does well, you are thumbs up, you did a great job of measuring stress and strain.

Chris Case 13:35

Alright, so that’s load. But we’re talking CTL chronic training load, it’s a little bit more complex. Let’s get into that now.

Why Is CTL So Confusing?

Trevor Connor 13:44

So, the first challenge you have with chronic training load -is what we were talking about in terms of that stress versus strain- Chronic training load is based on power. Power is an external measure, it says nothing about what’s going on in your body, It says nothing about adaptations. So chronic training loads part of your performance management chart. That chart is trying to show something about how you’re adapting how your body’s feeling. So it seems a little odd to say we’re gonna use an external measure that shows nothing about your body and use it to show what’s going on with your body. So they had to do a few things- So this is again, Hunter Allen and Dr. Andy Coggan who came up with these concepts- to essentially turn power into an internal measure. So the first thing they had to do to get to chronic training load was not use straight power, but normalized power. And we’ve talked about this before on the show, but normalized power is the data is smooth using a 32nd moving average and that’s based on the fact that physiological response when you’re looking at heart rate VO2 tends to have about a 30 secound, delay and response. So that’s trying to make power a little more physiological, then you raise it to the fourth power. Which is from a regression of blood lactate concentration against exercise intensity, the transferred values are averaged and the fourth route taken yielding a normalized power. So that’s a lot of mathematical complexity. The short of it is it’s trying to take power and turn it into something physiological. So normalized power and, this is really important, because people don’t understand this. You hear people all the time talking about well, my normalized power for the ride was x, let’s face it normalized powers is always are higher than average power. People want to use the bigger numbers. So they go, well look at look how hard I was going here’s my normalized power. You’re not using it accurately, normalized power takes power and turns it into an internal measure. So it’s not what was going into the bike, that’s average power. It is, How hard did it feel to your body, That’s normalized power. So if you go up a hill, and then come down the other side, and don’t pedal, your average power is gonna be low, but boy, that hill is really hard. So your normalized power is gonna be a lot higher, because it felt a lot harder to you. But that’s not saying you went harder. So just to make this really clear, if you have two cyclists side by side going up a hill, they weigh the exact same amount. And you want to know who went harder up that hill, or who went faster up the hill, you look at average power. The person putting out the average power probably went up faster. Normalized power doesn’t tell you that normalized power tells you- So if one person had a higher normalized power- that the hill felt harder to them, not that they went faster, not that they went harder, it just felt harder to them. So this is why whenever athletes tell me, look at my race here, look how well I did, here’s my normalized power. I always go back to them and say you didn’t tell me anything. I have no idea how, how fast or hard you were going in that race, I need your average power. I know how hard it felt for you, but I get that from heart rate. So that’s number one, power has to be converted to normalized power, because that turns it into a gauge of strain. It takes a measure of stress and turns it into an approximate of strain, how hard it was on your body. So that’s the first step in figuring out your CTL. The next step is completely based on FTP. So normalized power has to be broken up into zones. And those zones are all based on a percentage of FTP. So this goes back to Dr. Coggin’s classic zones. Then, and have I lost you yet here?

Chris Case 18:15

I’m following, but I’m looking at notes, I hope people out there that are also listening are either taking notes or they might have to listen to this multiple times. Because it just, you know, you see those three simple letters CTL, oh, how hard could it be? It’s really complicated.

What Is TSS?

Trevor Connor 18:35

Right. So the next thing that we have to get at is TSS. which is your training stress score for each of your rides. So, the way training stress score is determined is, your normalized power over the course of the ride is broken into zones. Then it’s weighted, it looks at the amount of time you spent in zone one, and weighted pretty lightly, looks at zone two weighted a little more heavily, time in zone three starts to get weighted pretty heavily. And when you start getting over threshold, then you really get a lot of weighting. So if you spent just a little time up in like zone five or six, you’re going to accumulate a lot of training stress. If you spend a fair amount of time in zone one, you’re actually going to accumulate very little training stress. Then all that is added together at the end of the ride. And there is no so- when you talk about power, power is measured in watts, when you talk about heart rate, heart rates and beats per minute- There is no metric for TSS, it’s just a number. But the way it works out is if you spent an hour at FTP, you would accumulate 100 TSS.

Chris Case 19:53

Yeah, there are no units associated with it. It’s just a number.

Trevor Connor 19:59

Exactly. Based on time spent in each zones, using the normalized power, and then they’re weighted to give you a training stress score for the ride. What is really important- and we’ve talked about this before. And we’ll get to this when we talk about the bad is CTL- training stress says nothing about how that score is generated. So you can do a really slow ride for four hours, and generate, say, 150-200 TSS, you can go out and do a killer interval workout for an hour, hour and a half, and also accumulate upwards of 150 TSS. So, you’re gonna get the same training stress score, but the rides are going to be very different targeting very different systems, and training stress says nothing about that. As a matter of fact, we’ve got a good quote from a previous episode, one of our first episodes, this is Episode 19, we have a good quote from Larry Warbasse talking about that issue with TSS. So let’s hear that now.

Larry Warbasse Explains How To Trick TSS

Larry Warbasse 21:16

TSS is how hard the day was. And I know like the exact definition is like 100 TSS equals one hour at threshold, I guess TSS is the one that I would pay most attention to of all those. TSS, to me seems almost like the most accurate way to quantify the training. But then again, and I don’t know the exact details of this, but I’ve heard there some arguments to say TSS isn’t necessarily the be all end all, because you can go do a two-hour ride that’s super intense, and get like 200 TSS. Whereas like, you can go do a six-hour ride, where you just riding, and you’ll have like 120 TSS, and those have totally different effects on the body. Just because you did two hours all out doesn’t necessarily mean it was harder than riding six hours. But I definitely think it’s a pretty good indicator, and a good thing to follow.

Trevor Connor 22:18

This is something I’ve seen, and I’ve talked to other coaches who have seen this as well, that anytime an athlete gets into CTL hunting, so we have all these different things you hunt, but there’s certainly CTL hunting of, oh the higher I get my CTL the faster and stronger I’m going to be. What I have seen is there’s actually an optimal range for each athlete. For some, it’s higher, for some, it’s lower. But as you learn your athletes, you’ll very quickly discover with one athlete, if he or she gets over 120, they’re in trouble. Where you have another athlete, and if they’re not over 120, they’re just not fit yet everybody’s a little bit different. So it’s important thing to know about them each individually.

23:01

Yeah, and I’d mentioned that it’s the same for training stress balance, which is the form. We see a veteran Tour de France athletes that can handle the third week of the tour, because they’ve built up those years of resilience and stamina. They can be in a negative state in the third week of negative 80, or whatever it might be (training stress balance). Whereas a rookie first Grand Tour rider hitting those numbers can literally crack them for the rest of the year. Yeah, it is a very unique picture for each individual.

Chris Case 23:38

Alright, so now we’ve got an explanation of TSS. Where’s the connection to CTL here? How do we get from one to the other?

How Are TSS And CTL Connected?

Trevor Connor 23:49

So CTL -And again, you’re now going to be surprised how simple this is after we talked about all that complexity- CTL is just a weighted average of your TSS over the last 42 days. So again, it’s trying to get at adaptation. So we’re trying to take stress turn it into strain, we’re trying to make this internal and it generally takes about six weeks to see an adaptation to any sort of training. So that’s 42 days. So CTL looks at the last 42 days, and it does weight more recent days more heavily than days 42 days ago, 41 days ago, 40 days ago. So it is a weighted averaging. But basically, if your CTL is 100 essentially what that saying is you’ve been averaging about 100 TSS every day for the last 42 days. So, that’s it. That’s all CTL is

Chris Case 24:58

That’s all CTL is it all Took you 15 minutes to explain that.

Trevor Connor 25:02

Yeah, well, all that other stuff is complicated, the CTL is actually surprisingly simple how that’s figured out?

Chris Case 25:10

Sure. Now is the specific formula as to how it is weighted. Is that publicly available? Or did they keep that a secret?

Trevor Connor 25:20

I have never seen it. I’ve read the articles on training peaks I’ve read some Hunter’s and Dr. Coggan stuff. It’s quite possible I was distracted when I got to that part of the book or the article. But I have never personally seen exactly how it’s weighted.

Chris Case 25:40

Ah ha! See I googled it before I asked that question just to put you on the spot and test you. On the training peaks website, I did find a formula It’s not as maybe specific as I was referring to in my question but here it is. CTL today equals CTL yesterday, plus, parentheses, TSS today, minus CTL yesterday, multiplied by one over CTL time constant. So if you know what all of that means you’ve been listening. And you know something a bit about math.

Trevor Connor 26:21

There we go. That was exciting. That’s probably why I haven’t dive too deeply.

Chris Case 26:26

Yeah, all that said, that formula, you don’t need to know the formula. It’s very helpful to know how this metric is constructed. It is, as they say, I think dimensionless it doesn’t have units, etc. All that’s somewhat relevant, but not the most important thing to know about it. It’s just we needed to set the stage with the definition. I think now what we need to do, if you’re ready for it Trevor, is to get into the good, the bad, and the ugly, which is the meat of the discussion here.

Trevor Connor 27:03

But one other thing to point out, we covered this pretty heavily in the past episodes, I’m not going to dive deep into it. But CTL is one of the three graphs, let’s call it your performance management chart, which you can find in most software. And all of these are what are called impulse response models. And that just simply means there’s a stress or strain. So there, there’s your impulse and then you’re trying to see how the body responds, there’s your response. But like I said we cover that more details, we won’t go into that in this episode. And yeah, let’s dive into the good.

What Is Good About CTL?

Chris Case 27:37

Yeah, let’s start there. What does CTL do a good job of estimating In your opinion, or in others’ opinions out there?

Trevor Connor 27:47

So this is actually where I was going to bring in that quote from Tim that we already heard. I think he gave the best summary possible, which is, this shouldn’t be used as a metric of yourself. It is great for coaching and training because you can see how the body is responding. And as a coach you can- or as an athlete who knows how to read all this data- you can make choices about your training. And that’s where CTL is really good, it’s chronic. So again, you don’t want to use CTL to make day-to-day variations. You want to look at it over time, and then the base season, you want to see that CTL going up, you want to see it rising at a good steady rate. When you get into the season, and you’re looking to peak for a race, you want to bring that CTL down a bit. You don’t want to be building big CTL right before a target race because you’re going to be fatigued. So that’s where it can be really useful as a guide for your training. And I thought Tim summarized that really well. So this is another study that talks about this, concepts of training loads. So this one is a 2014 study by Dr. Hobson, and it’s called monitoring training load to understand fatigue and athletes. And they had a great section where they talked about the value of monitoring training load, and they had four so I’m just going to read these ones. Monitoring load can provide a scientific explanations for changes in performance. So again, that’s helping you to make choices. Can aid and enhancing the clarity and confidence regarding possible reasons for change in performance. -Same sort of thing- So Three minimizing the degree of uncertainty associated with the changes. And four, load monitoring is also implemented to try to reduce the risk of injury illness and non functional overreaching. So that goes right back to everything that Tim was saying. This is about making choices. Notice this study did not say, five, the benefit of training load is seeing how strong you are.

Chris Case 30:11

Yeah, none of that.

Trevor Connor 30:13

It could be very valuable. Another thing where it can help. And again, let’s throw in another clip from Tim here. Well, I’m not gonna say CTL shows how strong you are. There is a correlation between performance and how hard you train how much training you do. Unfortunately, I tell athletes this all the time, if you only have six to eight hours a week, we can get you quite strong, but we can’t get you up to tour level. If you want to be a Tour De France level cyclist, you’ve got to train 25-30 hours a week, there’s no way around that your load has to be bigger. So there are ranges of CTL that you want to target to be able to perform at the level that you want to perform at. So if you’re a cat one rider, you need to be at a higher CTL. If you’re a cat four or five rider, you can be at a much lower CTL and be competitive. And Tim does a good job of explaining those. Those ranges.

Chris Case 31:16

All right, let’s check that out now.

How Tim Cusick Usses CTL

Tim Cusick 31:20

Most of my focus is on the CTL progression, how are they accumulating over time. Specifically, I have a system of kind of plateau and overload. People look at periodization of these numbers, you could put that idea into periodization. I think when we’re looking at CTL growing, there’s only so long you can grow CTL, you can keep accumulating training load and expect improved performance out of an athlete. And there’s only so long you can sit at a CTL plateau and expect an athlete to hold a level of performance. So I think when you start thinking about this idea of training stress score, of scoring these as external training load process. It really is about understanding the progression of that training load. That’s the science that’s giving me the ability to make better decisions. But I have to color in the content underneath that, how we’re gaining it. That is an art form, I mean I have some specific techniques, I bet Trevor has some specific techniques to that. For me, when I’m thinking about it CTL is not a prescription. And people need to really wrap their heads around that. You can put out some generalized numbers and I can give you some right an athlete. Once they get in the 70 to 80 range tend to be getting -and assuming the training content is good, not perfect, doesn’t have to be perfect, but good,- they’re probably going to have a performance improvement in that range, they’ll have another one and I don’t know 100 to 120 range of CTL, it really depends on the content, what they’re doing. Then for the elite athlete, you might see another around 140-145 and above. So you could put some generalized thinking to that. But that’s not a prescription. That doesn’t mean let me just put an athlete on the bike, gain to those levels. Just ride don’t worry about what you’re doing, just gather TSS, and you’re going to be great. That’s just some kind of numbers to shoot for. For me, it really is about building a purposeful training strategy. Understanding the ability of the rider and the demands of the event. Building content based off that, right? So first you build the workouts, then you understand the weeks, then you understand the month,- the four-week cycles, the three-week cycles, whatever you using,- then once you get a good grip of all that, then for me what I do in planning, I backfill in TSS. Then I’ll tweak that plan to make sure that the training load is plateaued or overloading and the time frames that I want them to work.

Chris Case 34:14

In terms of those ranges, Trevor, is it always the case that the ranges – for instance, as a cat one rider, you have to have your CTL of a certain range just to give the body the load it needs to be at that certain level- Is that always the case? I guess what I’m getting at is I feel like certain athletes, when they get of a certain age, they don’t have to train as much to stay at the level they were previously at it. Is that the case in your experience as well or do I have that wrong?

Trevor Connor 34:56

I do think there is something to that. I also think there is an individuality to CTL. So you can have two athletes that are, say a cat one cyclists, a quite high level. One might perform extremely well at 120-130 CTL, the other one might need to stay closer to 100. And going above that beats them up. I’m having a bit of an experience with that myself. As you know, I was trying to get back to older levels this year, when I was training full time and at my best my CTL- I always had a high CTL- I was up 140-150 and had no problems managing that. I tried to get myself, this spring, up around 120. I was finding particularly with work hours, that was too much, and had brought it down and I am performing much, much better.

Chris Case 35:49

Yeah, interesting. So there’s an evolution to this, you shouldn’t necessarily expect the CTL you put out in a previous year to be the one you need to hit or surpass in a subsequent year to perform better. It just doesn’t work that way, you have to put it in context of life just like so many things we talked about.

What Is The Bad Side Of CTL?

Trevor Connor 36:13

Well, so here’s where we’re getting into the bad. Remember, CTL says nothing- because it’s based on TSS and TSS says nothing about how that training stress how that load was produced- Neither does CTL. So if you change how you train, if you change the type of work you’re doing, that means that could impact your CTL. And if let’s say last year you train one way and this year you trained another way, you could have dramatically different CTL’s. You might be 20 CTL points lower this year but if you’re training more effectively, you might be a stronger, better cyclist. So the only way you can compare it season to season- Again, this is getting into one of the bad’s- is if you train the same way season to season. If you make changes to how you train, that will impact your CTL.

Chris Case 37:13

Right, and obviously the same is true if you could have the same CTL from season to season. But one year, you did all intervals and nothing else, and the other you did something more like base training all year. But you somehow ended up with the same numbers and clearly one produces a lot more stress on the body than the other in the traditional sense of the word. And you could be a drastically different athlete. Do I have that right. Is that also the case?

Trevor Connor 37:52

So that was somewhat of the case that I was dealing with. So back when I was training more full time and keeping my CTL up in that 140 range, I was also doing over 20 hours a week. So I wasn’t doing that much intensity, I was doing a lot of low-intensity high-volume work. This year, in the spring, when I was trying to keep that CTL high, I only had the time to train 13-14 hours a week. And I fell into that trap and I’m embarrassed by this. I started adding more intensity, I started adding more sweet spot work to get that TSS up. So I could get that CTL up. And that was a big mistake, because I was changing the nature of how I was training to target a number. And now we’re getting into the ugly and we’re going to talk a lot about that a little later in the show.

Chris Case 38:42

Yeah, another question in this, this might lead us into the realm of the bad as well. But I it’s on my mind, I got to ask, how much of a difference does – you know, you’re talking about back several years now, when you’re putting out numbers in the 140-150 range and now you’re putting out different numbers -how much of equipment and the accuracy of the measuring devices. And with the estimates of you know, FTP, and all of that play a role in how drastically different that CTL ends up being from year to year season to season especially over the range of a decade or so.

CTL Is Built On Too Many Assumptions

Trevor Connor 39:35

Well, so now we’re getting into my point number one in the bad. So let’s actually jump over there. One of the issues with CTL is a metric, built on a metric, built on a metric. CTL is built on TSS, TSS is built on normalized power, normalized power is built on a formula for converting power-which you have to make that assumption that yes, that that formula I trust it- and all those relies on FTP. So if you want to do something really fun go into training peaks-But you can do this with most software-particularly go to WKO, change your FTP and see what happens to your CTL. So if I dropped my FTP 50 watts for this season, my CTL is going to skyrocket, I’m going to be back up to the CTL I used to be at. Of course, that’s not realistic. I don’t have an accurate FTP in there. So one of the things that’s really important here is you have to maintain your FTP, you have to make sure it’s constantly accurate, if not, your CTL is going to be accurate or inaccurate.

Chris Case 40:52

And by maintaining the FTP, you don’t mean maintain it at a certain wattage, you mean to maintain it in terms of testing, making sure it’s accurate, making sure it is the number that is is truly your FTP,

Trevor Connor 41:06

your FTP doesn’t change, well, it does actually change day to day. But overall, it’s going to stay at about a similar level, for a certain length of time, it does adapt. So every year, basically you can see a change in your FTP in about a three to six-week period. So I would say every three weeks you need to be going and making sure that that FTP number and whatever software you’re using is accurate. Now, some of that software is, for example, WKO has a what’s called the mF TP, which gives you an estimate of your FTP and it’s constantly adjusting. So you can use that. I know some of the cycling computers will tell you when it detects a change in your FTP, but you have to go really hard for it to detect that. So there are ways where you can get alerted to know that there’s been a change in your FTP. But in order for CTL to be accurate, your FTP has to be maintained in the software, it has to be updated regularly.

Chris Case 42:10

Hmm.

Trevor Connor 42:12

Right. So that’s, that’s number one. In terms of the bad CTL.

Chris Case 42:20

All right, what’s number two? that’s a big one. I mean that that assumption upon assumption upon assumption, there’s a lot that could go wrong there.

Trevor Connor 42:31

So before we actually jump to the next issue, I just brought up the fact that FTP can actually change day to day and we’ve been talking about the individuality. So this would actually be a good time. We have a really good quote from Dr. Seiler where he actually brings up TSS, I think he also brings up CTL, but he talks about the arbitrary nature of them. He talks about how not only can these things change day to day, but one of his big issues is that the TSS you’re generating let’s say at the start of a four-hour ride at a particular wattage is really different from what you’re generating at the end of a four-hour ride when you’re really tired.

Chris Case 43:11

Alright, let’s hear Dr. Seiler now.

FTP Is Too Manipulative According to Dr. Seiler

Dr. Stephen Seiler 43:15

I never look at TSS, of course,I mean, my workout is going into training peaks, but I don’t really use it I have to be honest. TSS what does stand for training stress score. But what’s it measuring? It’s measuring some manifestation of external load, power relative to an FTP times minutes. And implicit in the TSS score is that every minute is the same. The 108th minute is the same as the 30th Minute. At that low intensity, you were riding that. And the reality is that you and I know that’s not true. That the 108th or 240th minute at 65% of heart rate max feels different than the 30th. But they are the exact same score in the algorithm, as far as I can tell-As long as the intensity is the same- So there’s issues here that, you know, what’s the difference between load and stress? And that for that reason, I don’t get caught up in TSS because I’m interested in what my body’s telling me about my stress. You know, what was the stress of this session? I don’t need a number that is inherently not fully arbitrary, but it’s it’s fairly arbitrary. Because there are differences- Even the same three-hour workout me yesterday versus me three days later- can be very different stresses depending on what my status is. I may even have a virus in my body I don’t know about yet. Does that you know what I’m saying? There’s so many things you have that are influencing the translation from load to stress.

Trevor Connor 45:18

I had that experience this weekend, I’m coming off of a really nasty virus. So on Saturday, I did my first long ride in weeks, I’m still not 100%. So I was keeping it slow. My TSS, total TSS, for that ride looks like a recovery ride. But I can tell you at the end of that ride I was looking at my map, seeing that my car was three kilometers away and go I’m not sure I’m going to make it.

Dr. Stephen Seiler 45:45

Anyway, hats off to training peaks. I mean they got this tool that people love, and they love it so much, they almost become religiously addicted to it. But it’s worthwhile to have a little bit of reflection about the arbitrary nature of it. It is basically we’re playing with math. And the body is not perfectly algebraic in the way that it works. So I would just give people a little bit of caution and how rigidly they interpret and lean on these numbers. I think that is what I find interesting is , that when you talk to the high-performance people, they are much less connected to those numbers, than the age groupers as a rule.

Chris Case 46:44

In North America, the road racing season is winding down. And cyclists are starting to think about their coaching and training for next year. Now is a perfect time for late-season inside test from Fast Talk Laboratories. You can think of it as your final exam on your training approach for the year. Did you training go well this year? Did you set a new high bar to beat next year? Our inside Advanced Test can tell you. It’s an objective view of your fitness and your energy systems after riding all season. Get your inside results from Fast Talk Labs today. And you’ll have a new fitness level to beat as your goal for next season. See more at fasttalklabs.com/solutions.

CTL Ignores Negative Impacts On Your Body

Chris Case 47:31

All right, Trevor, what is the second point that you’d like to make under the realm of the bad here when it comes to CTO?

Trevor Connor 47:40

So I’ve already addressed the fact that it doesn’t say anything about how the stress is produced, or the strain so that’s important. And we’re going to come back to that later in the ugly. The next thing is what Dr. Seiler hinted at. This was actually brought up in one of the studies- and I didn’t make a note of which study, I apologize about that but we’ll put all the references on the website- is that these models, so the these, impulse response models, they’re all linear. But physiology is not linear. So again, you heard Dr. Seiler talk about that, the strain after four hours is very different from the strain at the beginning of four hours. These -and we talked about the day-to-day variability, our bodies aren’t that linear, they just don’t work that way- And these models don’t account for that. So again, that builds a little inaccuracy into these. Which is why they can be very helpful looking at them in the long run for trends. But in the short run, you’re going to see a lot of that inaccuracy and you have to be careful and you have to be particularly careful about the end. This is what ultimately happens with the bad, looking at this number and saying I’m at 110 CTL Therefore I’m at the strongest I’ve ever been. It doesn’t work that way there’s too much inaccuracy. There’s too much of metrics being built on metrics, you just can’t look at it that way. Now, the one thing I do want to know is the two numbers people love to use to show how strong they are CTL and FTP. If you drop your FTP, your CTL goes up. If you raise your FTP, your CTL goes down. So which one are people going to prioritize do what the higher FTP with the lower CTL? Or do you want the higher CTL with the lower FTP?

Chris Case 49:45

You’re asking the wrong guy Trevor, I don’t know we should do a poll, ask our listeners. But hopefully they’ll say neither though, hopefully they’ll have learned from listening to us over the years that they should not put so much stock in either of those numbers being high. They should just train the way they should train and leave it at that.

Trevor Connor 50:09

They are valuable metrics to use for training, they are not -And so this is the bad that we’re trying to hopefully convince- They are not a measure of how strong an athlete you are. That’s not how they should be used. That’s not why they should be used. If you care about how you measure up the way to find out how you measure up his performance, go do a race, then you’ll find out how you measure up and the numbers not going to tell you.

Chris Case 50:38

And this gets into part of the other aspect of the bad here, which has nothing to do with performance either, which is the flip side of training. And that’s recovery. And if you’re so focused on keeping your CTL high, then you might overdo things.

The Ugly Side of CTL

Trevor Connor 51:01

Right, and now you’re getting into the ugly. So there’s two sides to the ugly, and you just hit one absolutely spot on. Which is really important. The other one and let me just there’s one last thing in the bad. That will lead to the other aspect of the ugly. And I’m going to quickly reference another study which we’ve talked about before, which is aerobic fitness and amplitude of exercise intensity domains during cycling. This was a 2012 study that we talked about before which really showed that most of the adaptations you see both in cyclists and runners are in the lower end. So we talked about Dr. Sailors three-zone model, so zone one being that below Robic threshold, zone two being between your thresholds and zone three being above your anaerobic threshold, most of the adaptations that you see are down in that zone one range, you push it up, which raises everything above it. The issue here is that if you look at the weighting, doing a lot of writing in that zone one it generates very little TSS, which isn’t really going to push your CTL up unless you do a whole lot of time. I have experienced this, really TSS and CTL were not a thing back when I was training full time, and thankfully I never looked at them back then now I go for an easy base mile ride you get in four or five hours you look at your TSS and your heart just sinks you go really that’s it.

Chris Case 52:45

it’s so funny to me the psychology of these numbers because people want to accumulate them in some way, CTL even more so it’s it feels like people are accumulating it like they are mileage or just volume. FTP is a little different. So yeah, the psychology of going out there and looking at a number afterwards and being slightly disappointed. I think I get it because we’re competitive people and we want that, we want to see progress we want to accumulate and we’re equating this number with that and maybe in our mind, we are stretching it all the way to this equal success. Or this is a successful workout if this is bigger and that’s just fascinating to me. It just doesn’t work that way I guess that’s why I find it fascinating. You know that very well you’re hosting this podcast on this very subject to correct people’s thinking about this but you also fall victim to it as well. To some degree.

Trevor Connor 54:01

That’s what kills me. I know this. When I’m doing my rides now- I haven’t fully removed TSS from my screen. I used to have it on like four different screens on my Garmin I’ve got it down to one screen – I still all the time see myself wanting to look at where my TSS is going. and I go you know you shouldn’t do that stop looking. It’s like an addiction. You want to see how hard this is. And at my worst particularly in the spring, I’d look at my TSS for the ride and do the calculation of my head, is my CTL going up is my CTL going down and it’s a bad place to be. As you pointed out, I am fully aware of it and still find it really hard not to fall into that trap. So the other person I want to bring in here is Iñigo San Millan who has been on the show many times. He is all about the physiology not about the numbers or in terms of using the numbers to say what you are as a cyclist. He loves the numbers in terms of saying how to direct your training and I think we have a really good quote from him talking about, if you focus too much on training stress and not recovery, that’s going to push you into overtraining.

Chris Case 55:17

Alright, let’s hear from Dr. San Millan.

The Dangers Of Overtraining

Dr. Inigo San Millan 55:21

Yeah, and this is a big deal of overtraining, right? Cause many times, many people who are competing in category ones, twos or threes or masters, right? They are people who are not professionals. So normally, they’re either working or studying, right? So they have other things, right? So they are at a higher risk of getting overtrained. Because they don’t have much time to rest or much time to have a very good dedication to nutrition as part of their recovery. And intuitively also many times they think Oh, I miss some high-intensity pace, right. So they do more. Also, they’ll do monitoring, we do a lot of blood analysis where you can see different biomarkers of muscle damage of decreasing hemoglobin, which is going to affect your oxygen-carrying capacity. And therefore it’s going to figure performance. And many times this is very typical in these athletes. You know They show up to races, and they’ve been doing a lot of high-intensity training, combined with high-volume days. And then they show up in the peak of the season, and they’re not doing well. They go up and they think Oh man, I need competition pace, I cannot produce more watts, my FTP, for example, was 350 and now it is 300. I have lost 50 watts, I think that I need to do higher intensity because it’s the summer, right? When it is actually the other way around in these people. which is part of the morning trend, right? It’s very important. And as we do more analysis, you see that this athlete is completely overtrained, and has deteriorated significantly. There’s la study published recently showing that non-supervised high-intensity leading to overtraining damages mitochondrial function. So it’s not just at the muscle level that you cause muscle damage, but also mitochondrial function, structural changes, and low-grade inflammation, hormonal changes. And this is what leads to a lot of people to overtraining, it’s very typical in these athletes, especially in Colorado, in the Boulder area, right, where they are extremely striving for extreme training and extreme diets, which is a perfect storm.

Chris Case 57:53

Yeah, well, we’ll have to save the questions about why people get into that mentality for another episode with a psychologist. So should we get back to the list here of the bad and the ugly?

The Importnace of Recovery

Trevor Connor 58:07

Right. So yeah, now we’re getting into the ugly, and there’s two sides to the ugly, and let’s dive into both. But in short, one is exactly what you brought up, which is the issue with recovery. And the other one is what I was bringing up, which is to get that CTL people start changing their training, and moving away from the training that we know is beneficial. And doing the training that produces that big TSS. So why don’t we start with recovery. We are going back again, here’s Dr. Paul Gastin who we had on episode 45. Talking about that balance between training, stress, and recovery and the danger of putting too much stock in stress and avoiding recovery as a result.

Chris Case 59:03

Perfect. Let’s hear that now.

Dr. Paul Gastin 59:08

Well the objective, obviously, is to improve and adapt. So we need to get our training loads right. And that’s not always an easy thing to do. We know that too little load is not appropriate, leading to poor performance, or injury. We also know that too great a load results in underperformance, and you start to get symptoms of illness, under-recovery, and often injury as well. So, what we’re really looking for is this sweet spot within our training. We need variety in our training, we need to be quite cyclical in how we do it. Sometimes I think particularly in endurance sport athletes the goal becomes almost training, When it’s about how many kilometers and how far I’ve gone. Whereas what we’re really looking for is adaptation and ultimately improve performance. So it’s working towards that and knowing when to be able to back off, knowing when to push hard, you’re not going to adapt unless you do train hard. But training harder the whole time is going to result in stagnation underperformance and probably illness and injury.

Trevor Connor 1:00:16

Agreed. One of the things I always tell the athletes that I coach is be as intense in your recovery as you are in your training. If you train that much harder, you got to make sure your recovery is that much better.

Dr. Paul Gastin 1:00:27

Ya most definitely! Michael Kelvin, who’s done a lot of work in the subjective areas of self-reports, he’s got a really nice model of I think, he calls it the cism model. It’s the balance between, you’re able to continue to increase your load, if you’re able to continue to increase recovery and maintain that balance. As soon as it gets out of balance, then that’s when you’re likely to struggle. That’s going to be very different for different individuals, you know, your training history, the age of the athlete, the modalities of exercise that you’re doing. There’s a whole host of things that will actually influence that.

Chris Case 1:01:09

I think this is one of those scary things for athletes, they do what they’re supposed to do in terms of a training load maybe they’ve done a training camp. They know that they’re supposed to do a recovery of some kind after that, maybe it’s three days, maybe it’s an entire week, and they’re taking it easy, and they’re doing what they should be doing. But they see that CTL number go way down, and they think to themselves, well, what did I just do that training camp for if I’m just gonna lose everything I just gained by taking the recovery? And that is the wrong mentality, do I have that right, Trevor?

Trevor Connor 1:01:47

Absolutely. And the real danger here is, it is amazing how quickly your CTL tanks when you take some recovery. If you take say, a week off the bike to recover, or you’re traveling with your family CTL can drop 20-25 points. Which, for a lot of athletes, the difference between their base and their highest point in the season is maybe 40 CTL points. So they’re just looking at their training tank.

Chris Case 1:02:15

Like they went back to the drawing board, they went back to square one.

Trevor Connor 1:02:21

Right. And that’s not how it works. It’s not how it works with your body at all. And I’ve done this with athletes again, and again and again, where they take a week off, and they’re really worried because their CTL is going down. Then you get back on the bike and they have a day or two that they’re rusty and have to get the legs working again. But then they go for a hard ride and discover my power is higher than it was before that recovery. Because what happens during that recovery, Remember this is the fundamental principle of training. You do damage to your body, there’s the strain, and then your body repairs and adapts in recovery. And this is the ugly, if you are really worried about that CTL number and you’re not willing to let it come down. You never give your body that chance to repair and adapt. So you have that really high CTL number. But ironically, what I see with athletes that focus on that is they kind of plateau and they get stale because they’re never fully recovered. They never truly adapt, and they never get as strong as they want to be. Even though they have that high CTL and that’s ugly number one.

Chris Case 1:03:37

Yeah, the second part of the ugliness that can be had with CTL, if used incorrectly, has to do with that notion of wanting to constantly feed the beast, feed the number, see those numbers going up. To the detriment of training principles that people know.

Train To Improve Not To Improve Your CTL

Trevor Connor 1:04:06

Right, so ugly number two is what you’re referring to. Which is the training to raise CTL as opposed to training for what’s effective. I’m seeing coaches that are doing this now to they are figuring out the types of rides that really ramp up that CTL number.- and I know I’m gonna get in trouble for saying this. You know, I’m a big believer in the polarized model. – But if you want that big CTL number sweet spot is the way to go. Because you go out and do a six-hour ride in zone two so below that aerobic threshold. Your CTL might only be 200 or your training stress might only be 200. If you go out and do a five-hour ride at sweet spot. -And remember, that doesn’t necessarily have to be that much higher, but you’re just above that aerobic threshold,- that ride can be double, it can be a 400 TSS ride, and that’s going to jack the CTL up. So what I see and athletes that are really trying to get that CTL up, they’ll start doing more and more of that in-between riding, let’s do more and more sweet spot. Because I can really accumulate those numbers. They never do the easy rides, they do some intensity, but they’re usually pretty tired all the time. So they have a hard time doing really high-quality intensity, and just end up in that in-between place. But boy, do they have a high CTL.

Chris Case 1:05:45

Yeah, they’re just chasing a number, instead of following some of the fundamental principles. And, you fell into this trap this spring, as you already mentioned. You couldn’t train the number of hours you used to, so you ended up incorporating harder rides to the detriment of your overall training, just because you wanted to see that number go up.

Trevor Connor 1:06:12

Yeah, I got to own that. I don’t like owning in that. But I got own that.

Chris Case 1:06:18

Sorry to do that to you.

Trevor Connor 1:06:19

Oh know, it’s fine I deserve it. So that practice what you preach, I was not practicing what I preach. But I have adjusted and my training is going much, much better. But yeah, I did fall into the trap a little bit -it was little things like I go out for my long rides. And let myself get up over that aerobic threshold, because boy was the TSS going up.-But yeah, I will say this right now. Because this is the question we get from a lot of people. If you are doing polarized training, and you’re not doing 20-25 hours a week, your CTL isn’t going to get that high. But the thing I want to reassure you, -and we’re going to kind of close out this episode with a couple examples- is that doesn’t matter. If you are training right if you are following the principles of training. CTL doesn’t say how strong you are. It’s the training right that says how strong you are. And I’m going to give you examples of people where CTL came way down, and they were at a higher level, not a lower level. So to all of you listening to us who are interested in this polarized training model, but are concerned because you’re seeing that CTL not as high as you’re used to. That’s completely fine.

Chris Case 1:07:35

Yeah, the end result of the ugliness that we’re talking about, is that you kind of chase the number you do things that you wouldn’t otherwise do because you’re focused so much on that number. You ride a little bit harder, a little bit more often, you maybe do more intervals than you should. And you either plateau, like Trevor has already mentioned. Or you get to this place where you’re actually kind of walking a fine line between overreaching, overtraining, some of these more dangerous areas because you’re so focused on a number and you’ve got the blinders on to all the other more important things that a sound training regimen would have you do.

Trevor Connor 1:08:29

Right. So I think that’s a good summary. And I’ll just give you the even shorter summary, which is effective training is applying the principles and balancing strain with recovery. That’s how you want to train and the CTL is going to be what the CTL is going to be and don’t worry about it. Ineffective training is targeting that CTL and doing it by focusing on the rides that bump up CTL and avoiding recovery because recovery will tank that score. And now, I want to finish out the ugly with actually a clip from Joe Friel. This is from actually Episode 82, where he talked about the last chapter in his book Where he made the point that adaptation and recovery are not the same thing, because my guess is some of the people listening to this right now are thinking oh, well, the way I can do recovery is a whole lot of foam rolling and a whole lot of stretching and then I can keep training hard and I don’t have to take that week off and tank my CTL. I feel that was something Joe Friel was arguing against saying, no you need that time to adapt. Foam rolling and all that sort of stuff isn’t going- it might speed up recovery. If you’re at a stage race and you need to perform the next day. It’s great for speeding up and having your legs feeling good for the next day-. But adaptation takes us the time it’s going to take. And to get that true adaptation, you’d need to back down no other way around it, you need to take that time. So let’s let’s hear from Joe.

Joe Friel Explains Recovery Versus Adaptation

Joe Friel 1:10:13

Late in the book I talked about,- I actually kind of throw in a curveball there, based on what we just talked about. -And that was a discussion about recovery versus adaptation, and that they’re not the same thing. And that sometimes it’s better for an athlete to be very open-ended about their recovery process, which is now being taken to include adaptation. And sometimes plans don’t do that sometimes athletes don’t know how they’re going to feel when they get to a certain point in the season, they haven’t experienced what they’re planning to do. And when they get there, they discover the load is much greater than they thought it was going to be. Now, what do they do? Do they continue on to the press ahead with the same plan? Or do they make changes to it because of what they’re experiencing. And my point in this in that later chapter, we’re talking about recovery and adaptation. The most important things is adaptation it is not recovery, the most important thing is adaptation. That’s the reason why we train is to adapt. If you didn’t adapt what the hell would be the reason for going out there and doing good workouts. And to explain that, for example, the difference between a recovery and adaptation. There’s lots of research showing that hot and cold alternating submergence or baths speed up recovery. There’s not a single research study that shows it speeds up adaptation. So you may feel like you’re recovered, because you’ve done certain things – you got a massage, or you’ve done all these things that we all know about.- But that doesn’t mean you’re adapted your body we don’t know right now of any way to speed up the adaptive process. It’s a biological phenomenon, which is really beyond what we know about sports science right now. But it’s at the heart of what we’re talking about here. And so the issue is that you’ve got to be able to differentiate these two terms, recovery and adaptation. And not be focused just on recovery, but also realize you’ve got to give your body a chance to adapt. And so what does that mean? Well, that means, especially sleep, which is when hormones kick in, and the body actually goes through the process of becoming stronger, if you will. And so even though I’ve talked about having a plan, I’m now toward the end of both talking about how you’ve got to be ready to deviate from that plan, because of the need to adapt, as opposed to simply recover. So I tried to sneak that in toward the end, because I wanted to push the reader to understand that all these other things are important. But this now becomes one of the most important things you have to also give consideration to. How are you adapting?

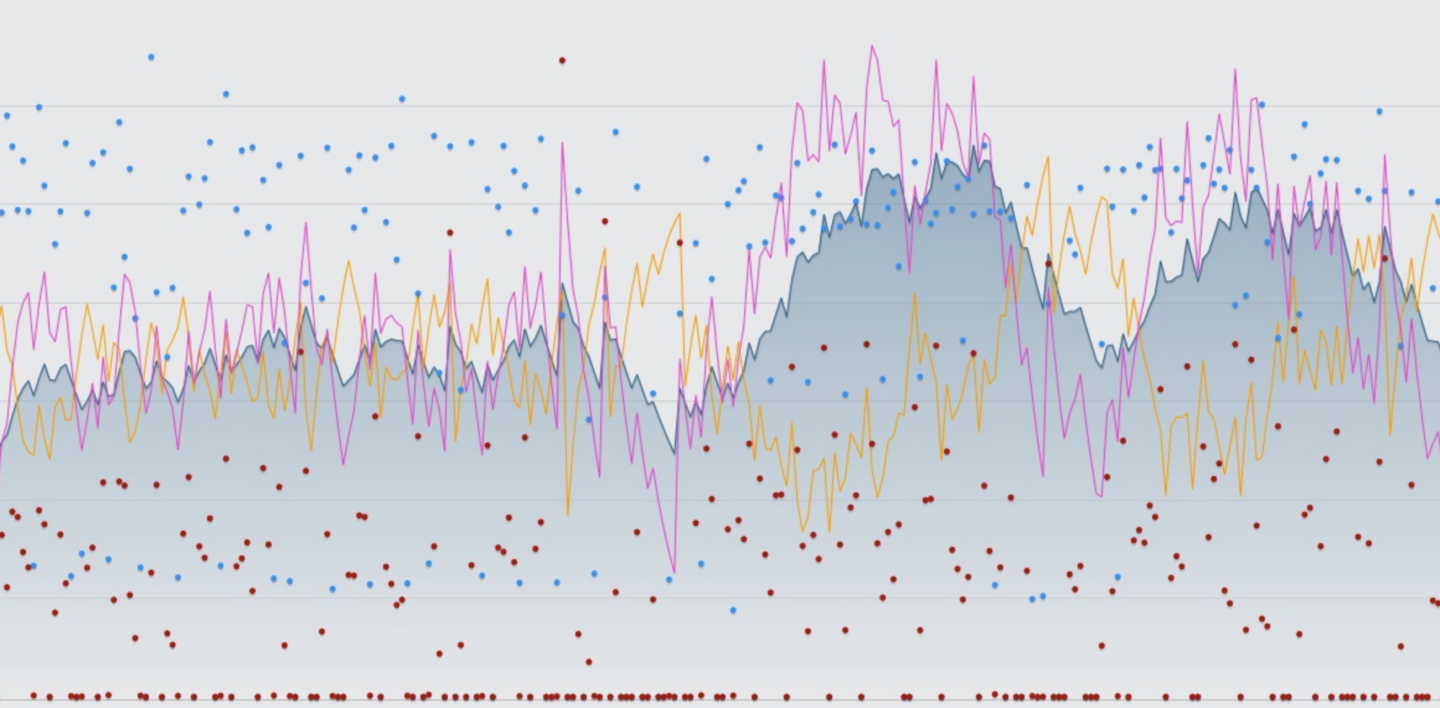

What Do The Good, Bad, And Ugly Sides Of CTL Actually look?

Chris Case 1:12:54

Now why don’t we dive into a couple examples that really highlight and illustrate the good, the bad,and the ugly about CTL? There’s a companion video workshop on our website that you can watch to see the data. But, Trevor, in words take us through these two examples of the good, the bad, and the ugly of CTL.

Trevor Connor 1:13:19

Yeah, so I am going to give you two examples of athletes I work with both are in their 50s. One is very recreational, he loves to do a Saturday morning group ride. He loves to get out with his buddies, but he’s never had a race license. He’s never done an official race. The other one is an elite cyclists somebody who I think is capable of winning nationals. So he’s very high level. So I just gave you the contrast of both, but show you some surprising things in terms of the CTL. This first athlete he’s 55 ,he was the one that I started this episode using as an example where all of his buddies were like, Oh my god, what’s your CTL you’re riding so strong. So he has this ride north from Toronto to this cottage country north of Toronto called Muskoka that he does with his buddies every year and when he first hired me that was one of his big goals. He’s like I go on this ride, I’m at the back hanging on for dear life. I usually get popped and they wait for me and I just want to be able to hang on at this ride. So this year, we set that ride as a big target It happened at the end of July. And you can’t see these visuals so I will give you the summary. We did a lot of base training we got his CTL up pretty high. We did a big training camp in March, he really had almost never been above 80 CTL and we were getting close to 90 so we did a little extra at the camp so he could see that 90 it was probably not smart on my part but he enjoyed So we did it. Then through the spring, we kept him right around 80. That was not his strongest point, then as we got into the summer, I would hit him with really hard training. But we’d only do that for a few weeks and then take a good rest to make sure that we weren’t overcooking him, that we weren’t pushing them into that overtrained state. When he arrived at that ride with his buddies, I’d like to say as CTL was right around 70, maybe 71, one of his lower points of the season. He went on that ride, and he was killing everybody. There was one guy there who used to race semi-professionally -I know I’m I used to race with him he is now like me getting a little older and just riding recreationally- And basically, the two of them went at one another in the latter half of this ride, it was about a six-hour ride. They were the only two that could put their face in the wind at this point. And like I said, at the end of the ride everybody else is coming up to going Oh my God, you’re so much stronger. What happened? You know, what’s your CTL and when he told them, he was down at 70, none of them would believe him. Because I think he probably had one of the lowest CTL’s of anybody on that ride. But quite possibly everybody else was a little overtrained. Maybe because they were focusing on that CTL. The other thing that was surprising to me is you look at the heart rate profile. And while this ride was killing everybody else. This was basically a base miles ride for him, his heart rate was mostly below aerobic threshold. So it was down in the in Seiler zone one for most of the ride. So this was a really successful day. And actually, the funny thing was after targeting is for so long, I just want to be able to hang with these guys. He was actually so disappointed with how easy he felt the ride was the next day he went out, did a two and a half-hour ride by himself where average 250 watts, just to do something hard.

Chris Case 1:17:04

Yeah. So having watched the video where you walked through the data that makes it even more clear that this performance was something he was very capable of. The point being a high CTL had nothing to do with improved performance in this case.

Trevor Connor 1:17:27

Exactly. So here’s a more stark example, let’s get to that more competitive master’s athlete. So he did get caught up in the CTL game. And we had a good base season, we are really raising his level, we had a big March and finished with a large training camp. Now if you’re looking at his weekly TSS right now, basically from beginning of March to about middle of May, he was with- only the rare exceptions,- putting out about 760 TSS every week. That’s a relevant number because he did his calculations and discovered that he could hold about 110 CTL if he was doing that 760 TSS every week. And that’s what he wanted. So we got into a little danger because there was a big March finishing with a big training camp. And then I wanted him to take a true recovery week and he didn’t. Now the week does look smaller, but it was actually a 400 TSS week and I wanted like a 100 TSS week.We’ve looked back on this and that really set him off on the wrong foot, he fell into that trap of I don’t want my CTL to tank. So that recovery week, I’m still going to do enough work to keep it from falling too far. And he came out of that week fatigued. And then we went into a series of four weeks in a row with racing, -actually more than that was four or five or six, I think. -But he just never got back on top of his training and because he was trying to hit that 760 TSS every week, he was just constantly cooked. And he’s going to some races, he performed well, some he wouldn’t perform very well. But just never feeling that good on the bike. And again, it was because he was targeting that number and the clearest example with him that I saw was, – he’s in Boulder, and there’s this training race in Boulder that goes every Tuesday and Thursday. And I know this race is a good hard race. I mean, this year, we had two guys that went to the Olympics for triathlon, who were showing up to this ride and they get on the front and drive it hard.- So when I send an athlete to a training race, I don’t want them to sit in and be smart, I want them to race hard. That’s the place to use it for training. So I kept telling him I want you attacking at this training race and for a couple of weeks he’d just sit in the field and never attack And in his notes, say would say I’ll attack next week, which is getting a feel for it this week. And after a few weeks of that he finally just admitted, not attacking, because I can’t. I’m basically just hanging on. And you can see that in the profile. Again, we have this video online, but you look at his heart rate, the whole race, -which is about a little over an hour, I think about an hour and fifteen -his heart rate just sitting at threshold. So that’s all he can do is just basically be pack fodder. After we realized that he was starting to cook himself and he was focusing too much in CTL. In June, we actually had to have several easy weeks, we really had to back down, then we got him to do a different approach to his training. Where we would do two, three-week blocks where we’d actually make those weeks bigger. So we increase the volume, his TSS was actually getting up in the 800- 900 range, we were making his hard rides really hard. But then after two, three weeks of that, we’d have a week where he would almost be off the bike. Like two hours 50-60 TSS total for the week, which he struggled with a bit but he was willing to do. We did kind of two blocks of that, and then saw where his performance was at. And it was extraordinary. Now, first, I’m going to say because of frequently taking a week, almost off the bike is CTL tanked. So I was telling you about that training race. I’m looking at an example of one of those training races back when he was to focus on CTL. His CTL was 107. But like I said he was just barely hanging on. So now we get to August CTL is now down to 82. So we’re talking about a 25 point drop, that’s huge. He goes to the training race. And I show this in the video, but the powers he was putting out in this August training race were much higher. His one minute, his five minute, his 20 minute, his one hour power We’re all higher in this August 3 race. But interestingly he said, I don’t know why they’re going easier now. This used to be really hard. If you look at the first 45 minutes of the race, his heart rate never even touches threshold. So he was now sitting very comfortably in the field. Even though he’s putting out bigger power than he was back in May when the CTL was 107. There’s this point where the course goes up this false flat Hill, it’s like 2%-3%. And at the end of it, there’s a couple of kicker climbs, and it’s all into a headwind. I always love to attack there. I recommended he attack there, but it’s a really hard place to attack you got to be really strong to stay away. And he broke away and held off the field for five minutes. They caught him right at the top so he almost pulled it off. Remember, this was a guy when a CTL was 107 was hanging on and couldn’t even attack now he attacked one of the biggest parts. Then a little later in the race just because he felt it wasn’t hard enough. As they were coming into the finish he got on the front of the field and just time trialed the field for 10 minutes. Then when they hit this kicker climb right before the finish, which is where riders attack. Even though he had been on the front for 10 minutes, he was the second wheel over the top of that climb. This was a fundamentally different rider than the rider in the spring. But really important to point out in the spring is CTL was sitting around 110 now his CTL sitting around 82, but he’s resting he’s recovering. He’s letting his body adapt. That tanks his CTL but it’s making him a better rider.

Chris Case 1:23:57

Yeah, you can really see this in the data. When you walk through both the course, the climbs, the power he’s putting out, the heart rate, all of that is very well illustrated in the data so check out that video on fasttalklabs.com. I think it’s worth going back just for a second and you’ve already mentioned the performance management chart, the PMC. There’s a lot more to that, that we didn’t discuss. ATL acute training load, TSB training stress balance, and with these metrics there’s a lot. We just want to reiterate how much more there is to the PMC and that we’ve actually spoken about it before.

Trevor Connor 1:24:47

Yeah, I’d actually thought about diving into those and how to use CTL, ATL, and TSB together to get some really good information. But we’ve actually been going for a while here and we have two good past episodes where we dived into that with the experts, I mean the true experts on the subject. So, I would say, for the benefit of time, if you want to learn more about the performance management chart and all three of these graphs that make up the performance management chart, check out Episode 42, which is with Hunter Allen, who along with Dr. Andy Coggan really invented this. And then the other one would be Episode 119, which is a whole episode talking about training load with Tim Cusick who is the brains behind WKO.

Chris Case 1:25:41

I know that was a lot. And we started out with a pretty deep definition of CTL. But I think that is a critical component here. It’s not as simple as you think, people often will take a complex metric like CTL and try to simplify it. If only to wrap their heads around it but there’s danger in that. And hopefully, we did a good job of expressing the dangers that you can fall into if you use it the wrong way. I think it’s worth reiterating. It’s not all bad. There are some good things about this metric and we highlighted those right up front, we wanted to do that. We don’t want to be just bashing this because there is some value. You can use it, If you use it wisely, It’s worth your time.

CTL Is Not The End All Be All

Trevor Connor 1:26:30

Yeah, I think that is the key message, which is it is A great training tool. This goes all the way back to Dr. Bannister in the 70s coming up with these sorts of models, and they’re very useful, but it is a training tool. It is not a measure of performance. And that’s where you get into the bad and the ugly.

Chris Case 1:26:52

We’ve said it many times throughout the show today. Don’t focus on CTL, don’t worry if it drops. We’re going to close with yet another quote from a great coach Kendra Wenzel, she has much of the same message to say so let’s hear from her now.

Kendra Wenzel 1:27:16

Well, like I said, if the athlete is feeling exhausted, then I would be hesitant to push through with anything. Unless for instance, we have a major rest coming up a day later or something it might be actually something where we wanted to push through. Are you negating gains? Again, it depends if you’re going to get that recovery soon enough. You know, I guess my first thing is always with CTL is all the data accurate that’s in there? You know if I’m seeing CTL drop, I first still need to make sure that all the training is actually in there and accounted for its TSS. I don’t know I guess I don’t I don’t panic a lot when I see drops in CTL just because there’s so many components that are going into it altogether.

Chris Case 1:28:15

That was another episode of Fast Talk. Subscribe to Fast Talk wherever you prefer to find your favorite podcasts and be sure to leave us a rating and review. The thoughts and opinions expressed on Fast Talk are those of the individual. As always, we love your feedback. Join the conversation at forums.fasttalklabs.com to discuss each and every episode. Become a member of Fast Talk laboratories at fasttalklabs.com/join to become a part of our education and coaching community for Tim Cusik, Larry Warbasse, Joe Friel, Dr. Stephan Seiler, Dr. Iñigo San Millan, Kendra Wenzel, and Trevor Connor. I’m Chris Case. Thanks for listening.