We talk about a subject that Chris Case knows well, and that our guest, Lennard Zinn, has lived for the last five years: Heart arrhythmias in endurance athletes.

Episode Transcript

00:00

Welcome to fast all the news podcast everything you need to know to run.

Chris Case 00:13

Welcome to another episode of Fast Talk. I’m Chris case managing editor velonews joined as always by the ever eloquent Coach Trevor Connor. Today we’re going to take a deep dive into a subject that I know well and that our guests Leonard’s in has lived for the last five years. Heart arrhythmias in endurance athletes. Leonard and I, along with dr. john manarola, wrote a book entitled The haywire heart that details how and why long term endurance exercise could cause a variety of heart arrhythmias. The topic of heart arrhythmias is in endurance athletes is broad, multifaceted, complicated, and in so many ways extremely important to investigate further, but we’ll touch upon many of the facets of the issue in today’s episode will detail the research, discuss warning signs give you an idea of just how hard your heart is working when you’re doing that set of intervals, or running a marathon. And of course, we’ll discuss at length the evidence that suggests there could be too much of a good thing when it comes to exercise. Of course, that begs the question, is exercise good for your heart? Absolutely, it is. Undoubtedly it is. In fact, it is undeniably the best medicine there is for preventing a host of cardiovascular diseases specifically, as well as generally a multitude of other diseases. It’s documented beneficial results would qualify as a miracle drug, if only a pharmaceutical company could figure out how to bottle it. But even miracle drugs have a recommended dosage and vastly exceeding it is not generally prudent. Can there be too much of a good thing? Quite possibly. And that’s what we’ll talk about today. In this episode of fast

Chris Case 01:59

pay Trevor, you go and ride in today.

Trevor Connor 02:02

I think I am. I think you and I are heading out to do some clients today. That’s true.

Chris Case 02:05

We might be doing some KLM hunting on Strava

Trevor Connor 02:09

we’ll see this we’re going with seppuku. So I think he might be getting some k ohms. We’re gonna be a little behind, huh?

Chris Case 02:15

Maybe? Well, it’s still good to put all our rides up on Strava health IQ is a life insurance company that specializes in healthy, active people like cyclists and runners. They’re able to give us favorable rates for life insurance. And they have a special website just for us Fast Talk listeners. www dot health iq.com slash Fast Talk where listeners of the show can go to get a free quote. While you’re there. Submit race results screengrabs of your Strava or Matt my run account or other proof that you are indeed a regular cyclist and you’ll get a better quote.

Chris Case 03:01

I’d like to start with a little story taken from the haywire heart. The sun shone bright on the upturn flat irons rock formations above Boulder, Colorado. It was another perfect day in a cycling paradise. Leonard Zinn, longtime member of the velonews staff and former member of the US National cycling team was riding hard of his beloved Flagstaff mountain, popular road in town that snakes were four miles and almost 2000 feet above Boulder. But on this day in July 2013, his life would change forever. 15 minutes into his attempt to set a new Strava kiom for the climb and his age group is 55 plus age group, he felt his heart skip a beat. It was something he had felt before but only at rest. He looked down at the Garmin computer on his handlebars and notice that his heart rate had jumped from 155 to 218 beats per minute and stayed elevated. He tapped the garment screen. Was the connection bad No it wasn’t he felt fine but eventually pulled the plug on the attempt, knowing that the distraction had disrupted any chance at a record. Later that day, he called his physician as a precaution. Much to his surprise. After describing the incident, he was told to head to the emergency room immediately. Then things took an even more serious turn. After a series of tests, the ER physician recommended that he’d be taken via ambulance to the main cardiac unit of the hospital for an overnight evaluation. Despite the initial alarm, his doctors simply prescribed rest. That seemed easy enough. So easy in fact that even though the he trusted his cardiologists and the ER doctor, he ignored the true depth of their warnings. While he obeyed their calls for rest for a short time, he eventually returned to his usual training plan. His only concession was that he did not resist when he was asked to wear a portable telemetric ECG unit known as a holter monitor. It didn’t disrupt his routine. What did disturb life and training were the annoying episodes that started to become more frequent during his intense rides. Now when his heart rate spiked, he experienced what felt like a flapping fish in his chest. more upsetting was the phone call in the middle of the night from a faraway nurse who had been monitoring the ECG readings from his holter monitor. She had some shocking news, his heart had stopped for a few seconds, Leonard finally admitted that something was definitely wrong. By October, he could do nothing to eliminate the episodes. He made every attempt to reduce the stress in his life. But intense riding and racing always triggered an episode of elevated heart rate and that fish out of water feeling. After further visits to his cardiac electrophysiologist he received an official diagnosis, multifocal atrial tachycardia. That’s when Xin ultimately decided to heed the warning he’d been given and quit racing. He also backed off from riding with intensity or duration. In doing so, he felt instantaneously downgraded from thoroughbred to invalid. He altered the very nature of his life in more ways than one. He was made to face the reality that he could never do what he used to do, in the same way that he used to do it. He now became interested in maintaining an activity level to sustain his longevity, rather than his fitness or speed, life changed forever. And in fact, Leonard’s story continues on to this day. And we’ll get into that later on in the program. Again, welcome to the program. Leonard, is there anything about your story that you want to tell people about over the last five years, how this has impacted your life?

06:37

Well, I went from somebody who was always trying to become faster at cycling, or cross country skiing. And to somebody who is a little bit afraid to do that, or a lot afraid to do that, that certainly, I don’t try and do that anymore. That’s a big, big shift in mentality for sure that it’s certainly not all bad. I tend to smell the flowers more, I noticed things like on that climb of Flagstaff, that Chris was mentioning, that when I do ride it, I noticed things I’d never noticed before, even though I probably written it almost thousand times. And I have more time to devote to other things, which is also not a bad thing. I’m not training all the time, I just can’t, I’d be going into a rhythm me all the time. I’ve developed other interests. So yes, it’s definitely been a lifestyle change.

Chris Case 07:39

And you know, I have a little implanted EKG monitor under my skin and my chest right on top of my heart. And I mean that that’s just one example of the details of my life that have changed having this bedside monitor and this thing under my skin. And we’re talking about someone who was on the national cycling team in the early 1980s, somebody who has competed at a very high level, both as a cyclist and a Nordic skier for decades. And I know that I I’m gonna say you’re sugarcoating it a little bit. You’re you’re at this point, you’re very frustrated. I can tell I can see it in your body language. Over the last five years, it’s been a it’s been an ordeal, okay? One day you’re out riding your bike, maybe it’s on Flagstaff mountain, you’re going pretty hard. All of a sudden, your heart starts racing, your heart rates, 225 beats per minute, it wasn’t that way two seconds ago, what’s going on? Maybe the garment is broken. He Keep going. Keep tapping on the garment. Nope, it’s not broken. He started freaking out. Your heart is doing something you don’t think it should be doing. Your heart is doing something you’re not familiar with. We’re talking about sort of warning signs here. And there’s two groups of warning signs. Those that really merit immediate attention. And those that should give you pause, you should definitely take notice of them. You should pay attention to them over the course of time. Of course, we can break those down a little bit further and talk about which do merit immediate attention. Do you want to talk a little bit more about that Leonard? And and maybe this is a good time to tell a little bit more about the aftermath of that first incident on Flagstaff where you ended up going to the emergency room. And then the further studies and tests you had to do over the preceding few days to start this long saga that you’ve been on?

09:41

Yeah. So I was doing similar to what Chris was talking about tapping on my Garmin thing That can’t be right. It’s saying 218 beats a minute and stayed that way for seven minutes. And finally I had the sense to stop and it came right back down. And then I was kicking myself for having done that because I oh well. I was on a Good pays to set a kayo am on this climb. found out later, when I called my primary care physician to ask for a recommendation for cardiologist, which was I thought that was being a rational thing that I would that I should go see a cardiologist. And they asked me why. And I explained what had happened. And they said, Oh, no, you need to go to the ER right away. So that’s a good example of a reason to go to the ER, if you see heart rates that you’ve never seen before, and they’re sustained like that, and you are relatively sure that whatever device you’re using to monitor them is correct, then that’s a good reason to go right in.

Chris Case 10:43

You also described it to me at times as this flopping fish inside your chest. So if there’s pressure on your chest, if there’s these strange sensations that you haven’t experienced before, those would also be warning signs that would need would merit immediate attention. Is that correct? The flapping fish? That was?

11:02

Yes, that’s correct. Yes, that that was sort of the sensation I had was also sort of a feeling rising up pressure in the left side of my neck, which seems to be most of the time that I have an arrhythmia that, I feel that course everybody is aware of the some of the warning signs of a heart attack, which is again different from what we’re talking about. But it’s a reason to go to the ER for sure, if you’re, if you have pain in the left side of your chest, your your left arm is going numb, those those sorts of things. And fainting is a very clear one. If you just start feeling lightheaded when you’re exercising, that’s, that is not good, you need to get that checked out. And same with breathing like you feel like you can’t breathe, you’re breathing as hard as you can, and it’s not getting in enough, you’re not getting enough oxygen, that’s also an indication that that’s something that requires immediate attention.

Chris Case 11:55

And a lot of people endurance athletes in particular will have some more subtle symptoms over over the course of of their lives, palpitations, some people will call them skipped heartbeats skipped beats, technically pvcs are pa C’s premature ventricular complexes or premature atrial complexes, those are warning signs of a different degree. They’re not as severe as the others we just mentioned, but they’re definitely something to pay attention to. They might not mean anything, they might be completely benign. But it’s worth noting and worth noting the frequency with which you experience them.

Trevor Connor 12:32

pvcs are actually quite common and very fit endurance athletes and right always a warning sign.

Chris Case 12:37

Yeah, along with that, if your power if you see that your power is dropping, if you’re feeling excessively sluggish or fatigued, or like like Leonard said, if you’re I think this goes back to his point about the dosage, if you’re irritable all the time, then there that’s a warning sign that something might be up. So those are those are sort of on the spectrum of warning signs from most severe to pay attention to but don’t definitely don’t freak out and probably no need to go to the ER right away.

Trevor Connor 13:07

And even that high heart rate if you if your bike computer suddenly showing to 20 there are other things that can cause that you can be going underneath power lines, you can be near a strong electrical signal. So right, yeah, I would say if you see that, and you’re not feeling that flutter in your chest or anything else don’t immediately run to the emergency room.

13:26

Yes. In my case, I was quite sure that it was an accurate number after I started paying attention to what was happening in my carotid artery and the fact that Yeah, I’m just up on this Lonely Mountain by myself No, no electromagnetic fields around.

Chris Case 13:45

So it should be said that, that day, your life changed didn’t radically change at first, maybe it hasn’t radically changed since but it has significantly changed since but it took a long time to get to where you are now. You’ve had your case study, your particular scenario has led you to explore a lot of different treatment options from supplements to ablations. I think it’s worthwhile for listeners out there to to, in a sense, step into your shoes and have have you take them through that arc of your story that that journey you’ve been on the difficulties, you’ve had just sort of the trials and tribulations of the different things you’ve tried for treatment to try to correct this issue and how it’s changed your your life in

14:38

a sense. You know, one thing I think I I would say right off the bat is it’s certainly given me more respect for individual medical practitioners. I’m saying this as a global V and taking a big assumption that we as athletes tend to think that we’re somehow special and that doctors don’t understand us. No, that was my reaction when measured, elevated proponent in my blood even though it just so happened that the ER doctor in attendance who was telling me you got to go in an ambulance to the downtown cardiac unit was the team doctor for the Garmin sharp professional cycling team. And he knew about stuff like this and dealt with much more elite athletes than me. And every step of the way, my tendency was to discount what medical professionals had told me early on for sure, like, you know, I went home and was pretty scared after spending a night in the hospital the first time and they and they did this catheterization, where they look to see if I had any coronary artery disease, and I didn’t and, and they did a whole bunch of other tests. And then I took the week off or so that I figured was, was justified, but then started thinking out, that was probably all just a fluke, it had, it really wasn’t real. And I pretty much went back to training just as I had and planning on doing the same races, and

Chris Case 16:07

there was some denial on your part, definitely

16:08

a lot of denial. And also, I made some decisions about well, that day, I didn’t have any, any electrolyte replacement drink in my water bottle. And I tended to never do that, Oh, that must be the reason that’s got to be the key. So

Chris Case 16:22

searching for reasons why it could have been that day on exactly circumstances. So I figured, okay, I’ll

16:28

have electrolyte in my bottle all the time. And that’s going to be the key. And for a long time, I didn’t have other incidents of a rhythm, and I was training hard. And then eventually I did. And so that sort of disproved that one, but they were like, I’m sure I couldn’t count on two hands, all the things that I’ve come across as like, Oh, that’s the thing, you know, oh, I’ve got too low level of iodine, I need to have more iodine Oh, too low level of magnesium. That’s the key and, and each time for a while, it seemed like that was working. And then eventually, I’d have a readme again and have to confront the fact that, that no, that was not it. I do think that over time, I’ve developed a way of living that’s that certainly more healthy than than I had at the time. But I have also come to believe that there’s no single silver bullet.

Chris Case 17:27

Now. I don’t want to discount that. I don’t want to move on from that too quickly. But I want to back up a little bit. And tell people some definition start with some fundamentals of, of what you’ve gone through what your heart has gone through and what an athlete’s hearts go through in in general, maybe we start with what is an arrhythmia?

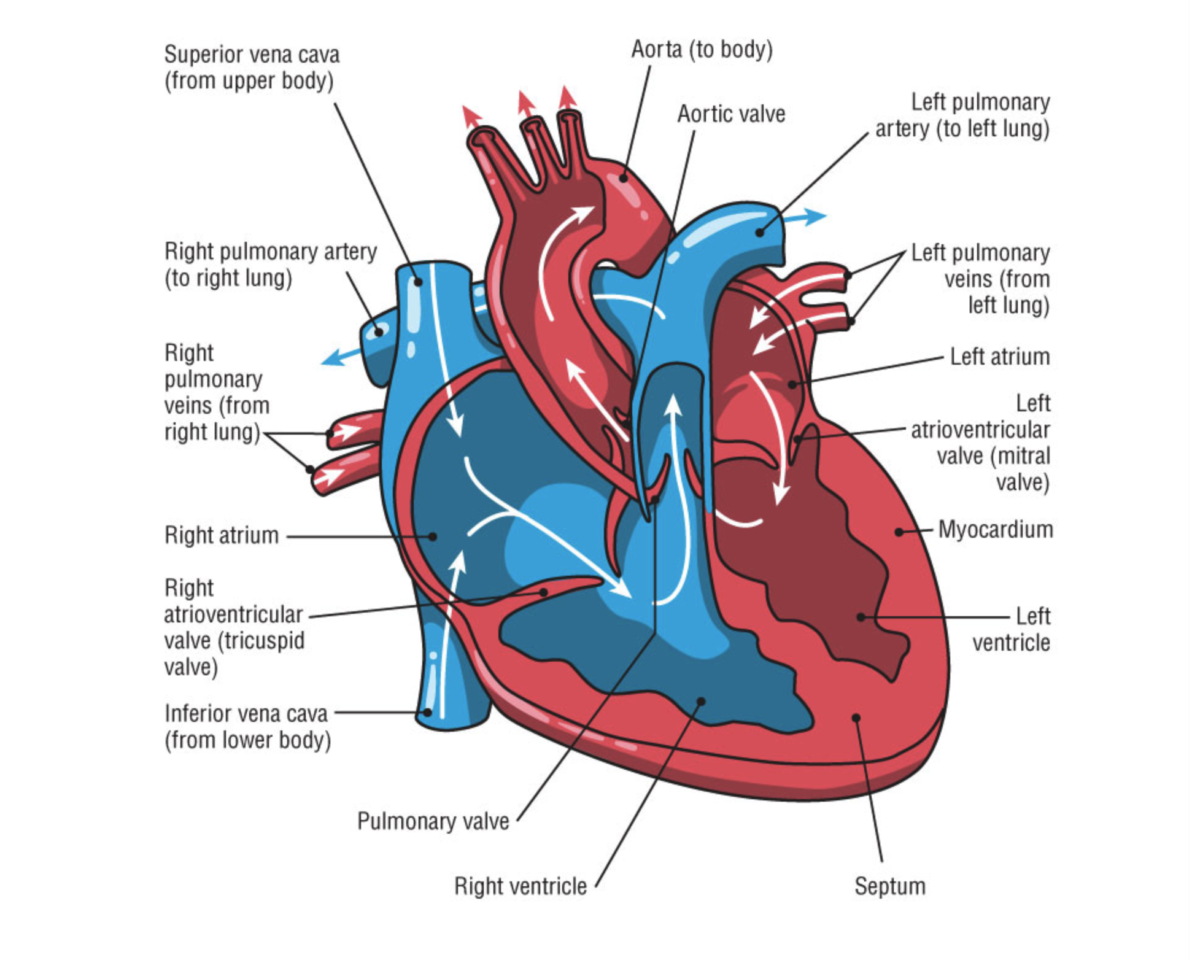

17:50

Yeah, so the normal way of heart functions is that there’s a cluster of excitable cells up in the upper right atrium, so that the heart is divided into two upper chambers called the atria and two lower chambers called the ventricles. And the atria collect blood from the body and blood from the lungs, and push them down into the ventricles. And then the ventricles push blood either out to the body or out in the lungs. And the sinus node signals the impulse to move this electrical current, which moves like a wave through all the cardiac cells, all of all the muscle cells in your heart. And this, this movement then starts at the top, from that right, upper atrium. When we say the right atrium, that’s the right as from the perspective of the person who who has the heart, this current moves down this wave of, of electricity, we call it depolarization of all the cells causes this contraction in the atria and it moves down to to another group of pacemaker cells called the atrioventricular node, above the H above the ventricles and at the bottom of the atrium, and the current stops there momentarily. In order to allow the ventricles to fill up, the atria have contracted, they push blood down to the ventricles with the ventricles have to fill completely and then then the AV node releases that electricity and sends it on as a wave down through the ventricles. So that the, it goes to the bottom of the heart and moves in a wave up the heart and squeezes the blood out through the, through the aorta, which is about in the middle of the heart. So this, this contraction comes up from the bottom of the ventricles and pushes the blood out. And that cycle continues over and over and over again,

Chris Case 19:51

that happens in a an instant that that doesn’t take very long for all of the of the words that you just used, takes a very, very short amount of time.

20:00

Yes, you can. Generally humans can tolerate heart rates up to around 220 beats a minute and still be able to fill the ventricles. That’s almost four beats every one second, that whole cycle can can happen beyond that. Some people can maybe go a little higher than that. But in general, beyond that, your ventricles won’t be fully filled with blood. And you’ll only be, you won’t be able to maintain the same kind of activity level power output, because you won’t be getting enough blood.

Trevor Connor 20:32

When one important thing just to point out with this is the ventricles do the heavy lifting of pumping the blood through the body, if your ventricles aren’t functioning, that’s when you’re in trouble. The atria help the ventricles, they basically allow pooling of blood in the atria so that the ventricles have more blood to pump per bead. But if your atrio stopped functioning, you can still live, it’s not going to function as well. But the the atria aren’t essential to survival, I guess, is a simple way to put it.

21:04

Yes, and most of the arrhythmias that we’ll be talking about the most common arrhythmias are ones in the atria. And so in general, and a rhythmic that starts with an A, or an SV, which sort of means the same as a mean supraventricular above the ventricles. Those arrhythmias can be can cost you power output, and can cost you the ability to do a number of things you want to do, but they probably won’t kill you, ones that start with a V. Those are a arrhythmias in the ventricles, and those generally will kill you unless you take proper steps immediately.

Chris Case 21:44

So let’s back up. What’s an arrhythmia? And yeah,

21:48

and he reads me as when the heart doesn’t follow the normal rhythmic sinus sinus rhythm of the heart, the electricity goes on a different pathway at a different rate than is supposed to happen in this normal sinus rhythm.

Chris Case 22:05

And you’ll often hear it described as the rock in the river where the electrical impulse the wave of electricity that’s coursing through the heart muscle hits a spot, maybe some scar tissue, some something else. And like water in a river, it’ll have to part around that scar tissue.

22:23

Yes. And then when parts around it, it forms a, an eddy current and current doubles back behind the rock and what water does and that similar thing can happen in the heart, where then the current would re circulate rather than continuing on unimpeded down through the heart.

Chris Case 22:40

And how does this differ? And this is I’m not I don’t mean to offend anyone, but the heart attack is a word that people throw around often. And I think there’s a lot of misunderstanding of what that is. And in its relationship to what we’re talking about here. How did the two differ?

22:59

That’s a very good question. Because generally, whenever anybody hears of somebody dying of a heart condition, something related to their heart, they call it a heart attack, or they think it’s a heart attack. And often the media is complicit in this that whoever’s writing the story doesn’t understand the difference, and will not clarify the difference, or we’ll actually call it a heart attack. So a heart attack is when you have cessation of blood flow through some of the cardiac arteries. In other words, that the arteries that supply the heart with blood, the heart itself needs blood in order to to continue to pump. And that’s separate from the heart that from the blood that’s being pushed through it, this is now blood that’s being supplied to the cells of the heart. And so if you cut off that blood flow, the heart can’t pump. And when that’s cut off, some of those cardiac cells die, and that’s called myocardial infarction. My word myocardium is the muscle of the heart. And infarction is where it’s that flow is interrupted and stopped. And that is very different from people who die of a rhythmic as you call that something like cardiac arrest, sudden cardiac death or SCD. And those are where the electrical system fails to cause the heart to get blood around your body. So the way they’re they’re separated is you have a plumbing problem, which is, which is a heart attack and then you have an electrical problem, which is cardiac arrest.

Chris Case 24:41

All right, so we’ve got the fundamentals of the heart explained a bit. And we’ve we’ve discussed what an arrhythmia is, we will get to a point where we’ll talk about the evidence for how arrhythmias may be produced in endurance athletes, but I think it’s worth talking about the The demands that an athlete puts on his heart in a way, some of these may be responsible for creating the the value that leads to arrhythmias. So I know when we wrote the book, you did a bit of research looking into the increased volume and the power output of the heart and some of those statistics, and I’m hoping you could share some of those. Now,

25:24

in general, it’s pretty amazing how much the heart can pump. And blood is not as thin as water, it’s, it’s a, an amazing thing that it requires so much pressure, first of all, to get through all of the miles and miles, thousands of miles of blood vessels into the smallest, smallest capillaries, and then and then return back through all of them, and through bigger and bigger veins back to the heart. And most faucets in a kitchen won’t put out more than about three gallons a minute, but the heart of a high level endurance athlete can put up around eight gallons a minute. And at a normal person at rest is sort of around one gallon per minute. So this elite athlete can multiply that by a factor of eight. And it requires a very efficient pump. And also the heart is pretty small and half of the pump is pumping blood into the lungs and back out. So it’s only half of its size that it’s actually doing this huge volume through the body. It’s a it’s a rather amazing device.

Chris Case 26:43

Yeah, how much how much blood does that equate to? If you extrapolate that over the number of hours that we’re out riding or bikes or running, and then multiply that by the number of years that we’re doing this?

26:57

over 70 years, there’s 60,000 miles of blood vessels in the body, there’s equators, only 25,000 miles around. So right there, you you have a sense of how much the heart has to do. Okay, so as I say in the book, the average human heart pumps 78 gallons per hour, or 1872 gallons per day, or 683,000 gallons per year. And giving them a railroad car holds about 30,000 gallons the hardest filling the equivalent 23 tanker cars per year in an 80 year lifespan span, which is 55 million gallons of blood to gush out that same amount of water, a kitchen faucet puts out at one and a half gallons per minute would be me need to turn on full for 69 years. Just look at your kitchen sink when you flip the the water on and how much water is coming out of there and how aggravating it can be when somebody leaves your faucet on. And you can see how much is flowing out that that’s what your heart is doing essentially all the time. Day in and day out.

Trevor Connor 28:05

What’s amazing about all this is a you gave the details of the electrical signaling that has to happen every single time the heartbeat, that you have multiple chambers that blood has to pass through, and that it never stops. I mean, this is a muscle and this is a muscle that never fatigues. I mean even to the point that all of us experienced damage to our hearts and our hearts have to figure out how to read or bodies have to figure out how to repair that muscle. Well, that muscle still working.

28:32

Yes, that’s right. That’s right. It’s not one that you can just when your legs get tired too tired from a hard workout, you can put them up on the wall and let them rest for even for the next day to put your heart never gets to rest.

Trevor Connor 28:45

The thing when I try to tell people how amazing our physiology is, the thing I like to say is think about your computer because I always think computers that are surpassing humans. Turn your computer on, keep using it for eight years. You can never restart it. You can never reinstall anything, you can never get

Chris Case 29:01

upgraded anything else

Trevor Connor 29:03

and you have to keep using it for eight years. Show me a computer that will actually last that long. Yeah, that’s

Chris Case 29:08

great. Even the fittest among us aren’t immune. The list of professional athletes diagnosed with arrhythmias continues to grow and includes World Tour riders, Iron Man champions Olympic medalists, and some of America’s most well known cyclists, including four time national cyclocross champion, Jeremy powers. I interviewed powers in the middle of the 2017 2018 cyclocross season as he was dealing with the onset of his arrhythmia power shared with me those frightening first experiences with his heart condition.

29:40

Well, I remember the first time that I had a palpitations very well because it freaked me out. I was raising the usgp in 2007. And I was coming around this corner and I remember I felt like a jolt in my chest. Oh, okay. Okay. I I went and got checked out for that. That was also subsequently the first usgp that I’d ever won. It, ironically, is almost doubled exactly 10 years ago, like it’s pretty close. So I remember that being like the first time that I noticed something of my heart. And then I had had, I’d had like palpitations, for a long time that I had gotten, like looked at many, many times, I had worked holter monitors and different things over the years, to monitor my heart, and to make sure that there wasn’t anything significant or dangerous going on. That narrow was a big problem. I think, this spring, I was getting these run ons where I was doing bass training, and my heart just kind of I was climbing, and I was mining at 150. And then it was at like, 200. In the first the first time it happened. I thought I had a panic attack. I had never had a panic attack before. But when I came home, and I looked up what happened. I remember it well. I was like laying on the side of the guy’s house, he has like a confederate flag blowing. And I remember like thinking to myself, okay, this is how it has, like, I’m up in the middle of nowhere. And there’s just this guy’s flag blowing in the wind. And I’m like laying in his yard, like freaking out. And I couldn’t get my hurry to go down for a pretty considerable amount of time. Yeah, I was pretty spun from that. I didn’t I know, it’s weird. I didn’t want to like do huge loops away from the house for fear of that happening again. So I was doing like, I was doing all these like micro loops kind of around the house to see if I could get it to happen again. And I was riding with a lot of friends. And it was trying to happen and I back off and kind of back off. I don’t really think much of it. I like just assumed that it was stressed. Like stressing about everything that’s happening, and I need to like really chill out. But being honest, I never really felt like there was some exorbitant stress, but I kind of backed it up to being having a weight loss. Maybe we’re just, there’s a lot of changes coming. And I maybe I’m going through this, I thought the doctors they offered some solutions, but I didn’t use any of them. You know, like, chill pill basically, I like No, I don’t. Like I started meditating.

32:08

Did they? Did they think that it was anxiety related, then?

32:12

They did? Yeah, they thought for sure.

Chris Case 32:18

I think it’s worth mentioning here and multiple times throughout this podcast. Exercise is good for you. We’re not suggesting that you shouldn’t exercise in any way. I think we would also agree that what we do the three of us sitting at this table and probably a lot of listeners out there. We do things that maybe go beyond what is healthy because we’re training for performances and things like that. And obviously what we’re talking about is doing something maybe too much to the point where it affects the health of our heart. And that’s where we want to spend a lot of our time today discussing the evidence around how much is too much what could be causing some of these arrhythmias to develop and people that are endurance athletes that have been doing this for a long time that continued to do it into their 40s and 50s and 60s, and 70s and 80s. Correct.

Trevor Connor 33:15

So I just want to throw one thing in because we are going to talk about some scary stuff. And when I read the book, there were certainly depressing moments in it because I certainly fit the bill for somebody going down this road. But when you guys started writing this book, you asked me for some research and one of the studies I found was they looked at Tour de France athletes since the beginning of the Tour de France and their average age of death was 11 years higher than the average population. And whether that’s because they’re genetically different, or because of their lifestyle. I can’t tell you this is just a correlation. And the other quick story I’ll share is when I was at CSU doing my master’s, I worked in a lab doing EKG data or ECG data on firefighters. And I still remember my first day in the lab, we had this firefighter on a treadmill and I was sitting there thinking, I need to call an ambulance right now this guy is about to die. And we obviously had a doctor who oversaw the whole thing. So my job was to go and get him I went and got him and I’m like you have to come and see this right away. Like I think we need to stop the test. Doctor comes over takes a look at it just kind of laughs because again goes you’re fine. But there were a whole bunch of arrhythmias You know, this guy was overweight, he didn’t exercise very much so what we’re talking about right now has a huge impact on your life but don’t take out of this that exercising is now bad for you. I’m still gonna say the choice between sitting on the couch and doing nothing versus exercise and you’re still going to be better off being a somebody who is active and exercises regularly.

Chris Case 34:57

And to follow up on that in the in the writing of this book. I spoke with many athletes that developed arrhythmias, and I’m not sure one of them would have changed the way they live their life in a sense, you know, they they admitted to perhaps bearing some responsibility for the development of it because they kept pushing themselves and pushing themselves. But when asked, What would you do differently the second time around, they all thought, well, I loved what I was doing. And I did it because I loved it. And I’m not sure I would change anything. And I know this is an interlude, but we have someone in the room sitting here that has developed an arrhythmia. What do you think Leonard? Would you have done anything differently knowing if you knew that this was going to happen?

35:41

Yeah, if I’d known how this is going to turn out, I would have been less focused on being so competitive as a Masters athlete, especially once after I turned 50. You know, when I was 55, I was winning most of the cyclocross races and that I entered and really, in the grand scheme of thing, only people who care about results in 55 plus masters, cyclocross races, are other people who compete in 55 plus Master’s cycle. Yes,

Chris Case 36:14

it says it’s a small group. Yeah. And not even their wives here. That’s right. Wives, or husbands depending on

36:22

Yeah, that’s right. But yes, it was very fun and fulfilling. And I and I liked, I liked the feeling of being fast and strong, in particular, being able to beat people younger than me. And that would have been hard to have given up. But if I could trade that for not having what I have now that I could have just sort of been able to continue to do the kind of rides that I really like doing, riding up in the mountains with my buddies, or riding on writing long rides across the whole state with in a day with my friends. I would trade that for all those 55 plus cyclocross results.

Chris Case 37:05

So, let’s start with the most common arrhythmia out there, atrial fibrillation, a fib, as some people will refer to it as maybe you could walk us through some of the key studies that have looked at the relationship between a fib and endurance exercise.

37:28

One of the things that I used to love doing was worldloppet, cross country ski races, these are races that happen. There’s one per country that’s involved, and they’re huge mass start events. And those are where the the most telling studies of atrial arrhythmias in masters endurance athletes have been done. The studies that point out these issues are always huge computer crunching of a whole lot of data from events because there is no way to do classical medical study on this subject, because you can’t do a double blind study where you have a group of control people doing one thing and that group that’s that you’re studying is doing something else you because you can’t conceal from somebody, their their exercise load their training load. So you have to do these massive number crunching by computers of, of data from lots and lots of people. And the two, maybe most important worldloppet ski races in the world are in Sweden and Norway, the one in Norway is called the beer Kubina rennet. And it has 16,000 people doing it each year. And that’s 54 kilometers over three big mountains. And the one in Sweden is called the Vasa lopud. And that’s 90 kilometers. And

Chris Case 39:04

and you’ve done both of these, correct?

39:05

Yes, I’ve done both of them. And that also has 16,000 skiers, both of them are feel limited that so it’s always that number. And the Vasa Lopa is 90 kilometers on a much easier course it’s three kilometer uphill and then kind of gradual downhill over the remaining 87 kilometers. And so the studies that were done on those show that in general, people that have done those races more than five times have double the likelihood of a fib compared to the rest of the population that they’re compared to which was either in Norway or Sweden. Another interesting statistic is that of 52,000 finishers of vasaloppet that were looked at almost 1000 of them had some sort of a arrhythmia. Another interesting statistic was that the number of times you did the race, increase the the likelihood that you had a fib. So people that had done it five times had about 30% more incidents of a fib than people had done at once. And similarly, the faster you were, the more the higher the incidence of a fib. So people in the Masters athletes in the front group, or front groups had, again, about 30% more a fib than people in the slowest group. And those to me are very, very telling statistics.

Chris Case 40:35

To follow up on those epidemiological studies of humans. There are also some very telling studies that were done in in animals, and maybe you could describe some of the findings of those lynard.

40:49

Now, there were a number of studies that were done with rats that were particularly telling and and again, you run into the question with rats is how much are is a rat like a human? First of all, and how can you compare what a rat does to what a human does, but in general, they would exercise these rats and they would found some pretty amazing things about cardiac remodeling and about a arrhythmias and about recovery from from these things, by studying these rats. So one of the studies, the train these, these rats, they made them run an hour a day, five days a week for 16 weeks, they thought that this simulated decades of training and a human and when compared with a secondary control group, the exercise rats showed lower heart rates, this is called enhanced vagal tone, your vagus nerve is what calms your heart, atrial dilation. So that atria got bigger atrial fibrosis, which is scarring in the in the atria and a higher vulnerability to atrial fibrillation, then the investigators also used atropine, to block the effect of the vagal stimulation on the heart to see if that it prevented the the a fib from happening, and it did so. So that was a key finding. It meant that the lower heart rates from the enhanced vagal tone was also partly responsible for the for the a fib. When they D train these rats, they also found that very quick reversal in that in that vagal enhancement. So in other words, their resting heart rates tend to to come back up to what they had been. And they tended to lose that that vulnerability they fit. But they did get fibrosis and dilation of the left atria. And that continued after D training didn’t get rid of that.

Chris Case 42:57

Trevor, anything you want to add here about that? Yes, we get it. These are rats, but how do they apply to humans? Is there any sort of general things you might bring in here that to add to that conversation?

Trevor Connor 43:10

This question comes up a lot well, which is a rat study, which is a mouse study. So it doesn’t apply to humans. And there’s certainly been cases, big cases where that was an issue on the ones I think of is with the immune system, where they discovered that marine so when you’re talking about mice and rats, you’re talking about marine studies, that marine T cells aren’t very plastic. So they they take one form and kind of stay in that form, where humans have a huge amount of plasticity. So you can have a T regulatory cell, which is kind of anti inflammatory, can actually convert to a what’s called th 17 cell which is highly inflammatory. And then after it’s dealt with what it needs to deal with, it appears that it can convert back to a T Rex. So that’s a case where humans were very different from the marine models. And so we actually went some of the wrong ways with the research until that was discovered. But for the most part, you you do get good clues with mice and rats, especially because their lifespan is two years. So essentially, if you study a mouse for six months, or you study in a quarter of its life, we’re humans, you would need 1015 years to do that sort of study. And I think when you use that as clues, and then say, okay, we’re seeing something in the Marine samples. So now let’s go to the gold standard, or the ultimate study, which is to apply this to humans that’s completely valid and fairly normal path. And you talk about that in the book that that’s where they started and now they’re starting to do the human studies on the heart.

44:40

That’s right. Another rat study looked at inflammation markers and found that a particular inflammation marker was greatly increased in the blood under high exercise loads, and that that then went back to normal levels. With D training and one of the things that we discuss a lot in the book is that both for garden variety cardiac disease that’s like hardening of the arteries, plaque buildup in the in the blood vessels. And a rhythm is a common component is inflammation. So there’s, there’s a difference between inflammation that’s related to a particular event or chronic inflammation and and if the inflammatory response continues after the pathogen or whatever has been eliminated, then this chronic inflammation tends to be bad for the blood vessels causing coronary artery disease, but also increases the likelihood of a arrhythmias too, and that these inflammatory responses in rats were also telling with with high exercise loads.

Trevor Connor 45:56

So Chris, I hear you’re the one who has the plague this time around. I think I was the one who was sick in August. How are you feeling?

Chris Case 46:04

I’m getting there getting there.

Trevor Connor 46:06

Oh, you got that good, gravelly voice for the podcast.

Chris Case 46:09

Yeah, I’ve been working on my podcast voice for a while. Now.

Trevor Connor 46:13

That’s dedication for you. However, generally, you are a healthy guy. And for Healthy People like you, there is health IQ, which is a life insurance company that specializes in healthy, active people, like cyclists, runners and variety of sports, they are able to give us a favorable rate for life insurance. And they have a special URL just for Fast Talk, which is www dot health iq.com slash Fast Talk, where listeners can go and get a quote, while you are there. You can submit race results screengrabs of your Strava or Matt, my run account. So Chris, are you heading over there pretty soon.

Chris Case 46:53

I’m doing it right now as we speak. And something that we didn’t actually talk too much about in the book. We touched upon it, obviously, the role that inflammation plays. But I know Trevor has done a lot of work with inflammation caused by nutrition in a sense. So I’m hoping that Trevor, you could add to this conversation here and talk a little bit more about that. Yeah,

Trevor Connor 47:21

there’s certainly a couple things to add. And actually, Chris and I are working on a future podcast talking about the role of inflammation in exercise, because for whatever reason, the way we evolved, when we exercise, you’re essentially doing damage to your muscles. Somewhere along the evolutionary chain, they said, Let’s use the immune system to repair that damage. So when you are finished exercising, you will get local inflammation so that your immune system can can repair and make your muscles stronger. When you’re keeping an imbalance your body is good at shutting down the systemic immune response. So it basically says, Okay, well, we’ll activate the immune system and your your quads where you were doing your work. But we’re not going to let that happen throughout your body, because then you will get something very similar to sepsis, and actually have this really interesting review that we read for a podcast A while ago that talks about this. And they coined this term systemic inflammatory response syndrome SRS Well, they didn’t really coin it, but they talked a lot about it. And sepsis, which can kill you is part of this syndrome, but they actually lumped exercise excess exercise into the syndrome as well, because when you are exercising too much and too hard, your body loses that ability to keep it localized. And then you can get a very systemic inflammation. Nutrition, we talked about this before it can be can also play a big role because nutrition can be very inflammatory. And in your book, you were talking about one of the cytokines that seemed to be be raised. And so I’m thinking out loud here because literally an hour before we came into this podcast, Chris and I were talking about and he mentioned TNF alpha, and I went Haha, which was in the book so so here’s a couple interesting things for you. And again, just thinking out loud, a lot of the current research style and this is I Evers freestyling right now. Okay, I’m what is it when you’re under the wave on when you’re surfing?

Chris Case 49:15

In the barrel in the pipe, Roy? Yeah, I’m

Trevor Connor 49:17

in the pipe here. So let’s go with that. So there’s a lot of current research, recent research coming out saying that, actually sugar is more the culprit in heart disease than fat that the finger was pointed in the wrong direction. And there’s actually even some pretty good evidence that it was intentionally pointed in the wrong direction. So you talked about TNF alpha been involved in your studies? Well, TNF alpha regulates the absorption of sugar from your gut into circulation. It also is activated in response to bacterial infection. So it responds to something called LPs which is a marker on your The bad bacteria that gets into your system. And so when your body starts detecting LPs, you’re going to upregulate TNF alpha and get some systemic inflammation. But it appears also that sugar can cause that. So I wondering if it is a coincidence here or not that endurance athletes tend to consume a lot of simple sugars. So whether this is just coincidental or additive, or none of the above, I don’t know. But ultimately, my recommendations are good recommendations in general that, again, you have your simple sugars when you’re competing, but be careful about eating too much simple sugars, especially outside of exercise, because you need to get that inflammation down. Also, some of those some of the research in TNF alpha and sugar is showing that consuming your omega three fatty acids can help to reduce some of that inflammatory effects. So it was a big tangent.

Chris Case 50:54

No, that was good, though, as well, something I think that we both know, is sort of missing from the book is that component, and it’s probably speculative. Well, what you just said is, I don’t know without having scan the research, I don’t know what is known about the if there’s any research that has looked into this, specifically when it comes to arrhythmias. But

51:19

well, I remember, this is not about arrhythmias. But I remember reading about a British study that had been done on ultra marathon athletes, and these were all athletes over 45, up to 67 years of age, I think and and they had to have done at least five marathons I think, but some of these guys had done like 200, and, and many double marathons. And they discovered extremely high level of coronary artery disease in these guys. And one of the theories I remember that they proposed in the study was just the huge amount of sugars these guys ate all the time while they were training and training and training and then during the events and, and I do think that that is a mentality that tends to be common among endurance athletes that Oh, five, work out this much I can eat whatever I want.

Chris Case 52:11

You’re talking specifically after the race. I’ve exercised my butt off today, I can go and just splurge on whatever I want.

Trevor Connor 52:20

Exactly. Yes. So I think the one thing we can say safely is that a lot of endurance exercise has an inflammatory effect on your body, that was probably contributing to some of these hurt conditions. So anything you can do to reduce that inflammation is going to help and diet is certainly one way their diets, Western diet is very inflammatory. There are other diets that can reduce inflammation, I would say the other thing is recovery. I imagine a lot of these people are really good at exercising really hard, weren’t good at resting. Yeah, I

52:52

think that’s true. Resting, of course, has a has a, an effect in reducing inflammation. Another thing that I think we’re all aware of is that is that stress creates inflammation. And that doing anything you can to reduce your stress level, which if part of your mentality is to be concerned about your results and worried about that, that that in itself, can also be adding to your inflammation.

Chris Case 53:23

So Leonard, I know that right now, you were a link monitor embedded in your chest. It’s made by Medtronic, it comes with I think you mentioned the little clicker that is allows you to click when you have the feelings of an arrhythmia so that it was recording a certain amount of time. Previously, you’ve used a device that hooks up to your your phone, maybe you could describe some of those devices and the data that comes from using them.

53:50

There’s another brand I can’t remember it that also does a similar thing besides the link monitor. But I think when I first started having these issues five years ago, that those either weren’t around or weren’t I nobody ever recommended them to me but the one thing they did recommend was a holter monitor which is is a portable EKG and you know, and I did a lot of cyclocross races I did a lot of stuff with that thing on and it wasn’t that bad. And it it has its own essentially little mobile phone that sits in your back pocket. And, and like the clicker on the link monitor, there’s a button on it that you push when you feel something weird happens. So you know that it recorded that and otherwise it has just like the link monitor both of them, you set them up when you want it to be triggered, like over a certain heart rate or whatever. And it also looks for specific weird things where it specific looks for, for distinctive patterns in the EKG and if it thinks it sees a fib or or some ventricular arrhythmias, it will automatically a lot of medically record those as well.

Chris Case 54:54

A little less sophisticated though, is this iPhone or phone device that that people can use For

55:00

Yeah, so cardia k AR di A is a an app that you can also find on the iTunes Store or Google Play or whatever and it’s a cell phone app that you press your fingertips on the on these two metal electrode or metal platforms pads, yeah, metal pads, and it will automatically diagnose your, it listens for 30 seconds to your, to your heart rate and creates a EKG from it and, and will tell you that it’s normal, or it’s or it doesn’t understand what it is or or it’ll actually diagnose some some a rhythmic conditions. And that’s a worthwhile thing. It’s like 100 bucks for the deal and downloading the app is free. So not a big downside of that either. And,

55:52

well, I’m

55:53

a pretty data driven person, I suppose. But But I don’t think I can have too much data I like I like having more information rather than less. And it’s something that I’ve done, I can, I can email it to doctors, I can have other people look at it and and it can improve the chances of getting a good diagnosis, I think,

Chris Case 56:12

and you have now had two attempted ablations I say attempted because in both cases, they failed to pinpoint the arrhythmia and be able to stop the, the misfiring of your heart. So let’s back up a second and explain to people what an ablation is. I don’t want to say that ablations are now commonplace, or that people are getting too relaxed about them, in a sense, oh, if I get an arrhythmia, I’ll just get an ablation, I’ll be fixed like that. And I’ll be on my bike and riding the next day. But there’s people are getting a little bit more familiar and maybe a bit casual about them.

56:49

Okay, so first of all, I want to address that from a global perspective. I think that yes, I’ve been trying all the alternative things that I think have a low chance of screwing me up and have a possible upside and I’ve been trying all the latest high tech medical things that I could think of that could potentially improve my condition. And ablation is a procedure in which you’re lying on a operating table in what’s called the EP lab and electrophysiology lab. It’s essentially a operating room, and you are connected with lots of EKG leads all over you. And the surgeon, which in this case is called an electrophysiologist. Cardiac electrophysiologist punctures your femoral veins on either side of your groin, and puts in catheters that he or she then advances manually, all the way up into your heart. And these catheters then are both ones that can detect electric fields, and ones that can produce them or can freeze things, and then the arrhythmia. And in my case, this is where that the buck comes in the arrhythmia is then stimulated in the while the patient is lying on the table by a combination of electrical impulses and drugs flowing in through a IV in the vein,

Chris Case 58:19

adrenalin caffeine things like that are

58:21

Yeah, so stimulant drugs at terpene. ISO prolene, which is a synthetic adrenaline, number of stimulants can be put into the system to try and to try and simulate the conditions under which your arrhythmia occurs. In my case, my arrhythmia only occurs during hard exercise. And I have now had two attempted ablations. And the first time I was under general anesthesia, and for three hours, they tried using these methods to get my arrhythmia to go and couldn’t and then they finally woke me up for the final hour. And thinking that maybe the anesthesia was calming my heart too much and tried to do it then and also were unsuccessful in in producing the, my arrhythmia sustainably enough for a long enough period of time. Because what they catheters in, they’re designed to do is to detect where the current is flowing and then it goes to a computer that that then create can create a map of the heart and where the currents are flowing. And then once this map is produced, then the doctor can then pinpoint a place on on where this current is flowing and kill some cells in that area. And that’s what the ablation is called as this killing of some cardiac cells in order to stop the current and those are that’s either done with with radio frequency from one of the catheters or it’s done cryogenically by freezing, freezing some cells

Chris Case 59:53

and what’s the thought behind killing that point of tissue

59:57

that the way electrical signals propagate through the heart is from one living cell to another by that the cell has to has to open certain channels in its membrane to allow ions to flow in one direction versus the other. And that’s how the current flows through. And if the cell is dead, no current will flow there. So if you have this aberrant current flowing through that point, and you kill those cells in that area, then it’s not going to be able to flow there. And the hope is that then the remaining flow will just be normal sinus rhythm, electrical flow. If it’s successful, the person really can go back to doing exactly what they were doing, and presumably have, have no ill effects,

Chris Case 1:00:45

the number of the people that I spoke with for the book, and in writing their case studies, they would have an ablation, and it might quote unquote, it might take for a while, meaning it might work for a while, but then they’d go back to what they were doing. And they might have to go in the second time, because maybe during the mapping in the ablation, they didn’t maybe get all of the cells is that a risk that someone takes that they have an ablation, and it works for a time and then they have to have it again, and they might have to have it a third time for it to fully work. And in between, they might think they’re cured, but they’re still pushing themselves, is there a risk that they could lead, it could lead to some other issue?

1:01:30

Well, in general, I’m led to understand that a relatively benign arrhythmia can lead to other rhythms, I have what’s called focal atrial tachycardia. And I have been told many times by my electrophysiologist, that chances are very high that I’m going to develop a fib at some point. And that, that tends to be what these things do. Now, I’ve also been told that the more that I go into the arrhythmia, the more I’m tending to train my heart to have the arrhythmia. And that’s one reason why I’ve tried to avoid going into it except my most recent ablation attempt, I intentionally went into it as much as I could the last couple of weeks to try and make my heart sensitive enough. And I did the ablation, without anesthesia, also as an attempt to increase the likelihood of getting it, but it was unsuccessful anyway. And I, I think that in any case, going into a rhythm is can inspire further arrhythmias. And, and if you’ve gotten an ablation that you think worked, and it didn’t, and you end up going back into the air with me, I think you’re at the same level of risk you were before of developing another arrhythmia. And when you look up a blasian, on Wikipedia, you’ll see these statistics like 97% effective and all this sort of thing. Well, my experience is talking to people. I know a heck of a lot of people that had a successful ablation, but it took three four times, right, or, or, you know, I do know, some that it worked on the first time, but also many times where they thought it worked, or they partially got it or some of these reentrant atrial tachycardia is you have what’s called a slow pathway and a fat fast pathway of a circular current flowing and that maybe they got one of the pathways and the other one still exists. And, and so those statistics are very misleading. I think that has not been my experience, just asking enough people that I’ve talked to, there’s no way they’re 97% effective. I went in the first time thinking, Oh, yeah, this is just gonna be Piece of cake. And I’ll be walking out of here, I’ll be the same athlete, I was afterward. And I don’t think you can take that for granted.

Trevor Connor 1:03:52

I certainly think there’s a, you need to be very conservative with them. You’re talking about killing heart cells. So you want to under kill and maybe have to do the procedure a couple times versus kill everything that’s possible and end up with a very weakened heart. Yeah,

1:04:07

that’s right to another thing that’s often said about ablation is very low risk procedure. Yeah, that’s true. But there are risks. And in addressing what you’re talking about, Trevor, there’s, in my case, I know that my ablate my, the focus of my atrial tachycardia is on the back of my heart, the back of your heart sits against your esophagus. And if the doctor overheats, are over freezes the back of your heart and damages your esophagus, the patient dies from that. So there is there is definitely a a risk that and then anytime you’re punching holes and in veins and whatever, there’s a bleeding risk. So yeah, it’s a it’s a wonderful procedure, that it’s that it’s fixed so many people and it’s not entirely benign either. Right. And

Chris Case 1:04:55

I think the ultimate point is that it’s there’s no guarantee that it going to work for you,

Trevor Connor 1:05:02

Chris and I interviewed Dr. Steven Siler, one of the top exercise physiologist in the world for another podcast. But while we had and we asked him about heart health, knowing he lives in Norway, where many of the studies on exercise and heart health have taken place? The answer he gave surprised us, but also showed that no one is immune.

Chris Case 1:05:18

You know, a lot of the research on arrhythmias in endurance athletes comes from stuff from the birkebeiner and vasaloppet. And some of these big cross country ski races in in Scandinavia, and I didn’t know if you had any relationship with those researchers are had any thoughts on the matter about heart arrhythmias in endurance athletes?

Dr. Steven Seiler 1:05:43

I have a relationship to the problem because I’ve had atrial fibrillation. Okay, I’ve had cardiac arrhythmias. In fact, after five years of kind of not having any problems, I’ve had a new bout that’s I’ve struggled with since December. But yeah, so I have had atrial fibrillation. Two times I’ve been in hospital and I had to be put under and shocked out to read to convert my rhythm back and I’ve colon and look found case studies and figured out that I could if I develop atrial fib, I could, I could go out in the woods and do a very careful progression with my running and kind of read, bring the the running intensity up to enough to kind of recapture my own heart rate. And so this is an interesting issue for me, because I’m right up in the middle of it, I’m 52. And in my mid 40s, this hit me atrial fib and, and so I probably am representative of this group of people that are 35 to 55, that have time and do some training. And there seems to have been this epidemic of cardiac arrhythmias, and particularly atrial fib. And we don’t really know exactly why, whether it’s the intensity or the volume, or both. But something is there, I have a naturally low resting heart rate. And if I get to fit, everything’s relative. But for me, if I get to fit, my resting heart rate gets too low, I get in trouble. I develop some arrhythmias. So I don’t have the answer to it other than the fact that I’ve had to learn to be very disciplined about the warmer drinking, I take magnesium, because I think it does help me a bit there. So I’ve just had to develop my personal recipe for dealing with my own heart. Because I am not going to quit, you know, I’m too stubborn. So I tend to believe that I can self manage until it goes badly wrong. So I’m not I’m definitely not a model for for doing everything by the book when it comes to medical guidance and all this stuff. I didn’t know. But I just I appreciate the question. I’m glad if people are looking at this.

Trevor Connor 1:07:51

Dr. Seiler said there’s no way he’s stopping. But is there such a thing as too much exercise? Let’s get back to that question.

Chris Case 1:07:59

Leonard and I have spoken about the topic of heart arrhythmias in endurance athletes quite a bit. We’ve done a number of podcasts with other people. And inevitably, the question comes back to us how much is too much? Where’s the line? How do I know when I’ve gone too far when I need to dial it back? Is it long rides that are worse than intense rides? These types of things that come down to almost like a dosage? What’s the dose of exercise that I need to be healthy, but not go too far and develop something develop a heart condition? And it’s a hard question to answer. You talk to some people and they’re really good at resting. Some people are. But if it’s a triathlete, they’re stressing about the fact that they have to train but they also have to fit in three types of training into their life, and maybe they have a job and maybe they have children. So all of the factors involved in understanding what is too much or making it extremely complex, if not impossible. I wonder if you have some thoughts about that. And anything that can be understood from the research as to what is too much.

1:09:14

I think we all can agree that if the effects of exercise could be put in a bottle, it would be a miracle drug that somebody would love to sell and become billionaires doing it. But that with any drug, there’s a there’s a dose and you can overdo the dose with even water, you can drink too much water and die from that. So exercise needs to be looked at from that perspective, I think and since having an arrhythmia, I would say my way of looking at this is what am I doing this for? If it’s just clearly just pure pleasure that I’m doing it for, then I’d say I’m staying well within the dosage but if what’s motivating me is much more external factor rather than the intrinsic joy of doing it on its own, then that’s when I question whether the dosage level is overdone. If you’re telling yourself, I’ve got to do this, or do if you’re telling yourself negative things, I’ve got to do this because if I don’t, I’ll be not good enough, not fast enough. From my perspective now, and looking back, that’s not worth it. And that is indicative of some of the sort of things that you’ll that you’ll hear your your inner voice saying to yourself, if you’re overtraining that overtraining is another way of saying you’ve overdone it, your power output has dropped, your your enthusiasm for life has dropped, your sleep patterns are disrupted, your eating patterns are disrupted, you’re, you’re less fun to be around. That’s very clearly going over the dosage. over the span of years, it’s a little harder to say, but my own recommendation is keep it within the fun zone. And then you’re you’re more likely to be staying within the proper dosage. One

Trevor Connor 1:11:07

things I really liked in your book is you actually had a quiz in there for exercise addiction. I actually took that quick quiz thinking I’m totally gonna fail this, I’m gonna be a complete exercise addict and was shocked to find out I actually did pretty well on the quiz. Yeah, well, I looked at the answers before. But I really liked that. If you you give a comparison. It’s it’s like nutrition, you there’s two ways you can approach health and body weight, you can say I want to be a healthy person at a good lean weight. And I’m going to try to eat a healthy diet to get there, that’s a good approach, it’s probably going to help longevity. On the flip side, you have things like bulimia and anorexia, which are a very unhealthy approach to take to it. And what that’s what I got out of that quiz. And what you were saying in the book, and just now is, there are two approaches you can take to the exercise. One is to say, this is something I enjoy, I want to be very committed to it, but I want to do it in a healthy way. And that’s probably going to lead you in good directions. Or you can be an exercise addict, too. If you don’t exercise in eight hours, you start panicking and feel you need to do something that can lead you in, you’re certainly not going to get enough recovery, you’re not going to keep yourself in balance. And that’s probably going to lead you down bad roads.

Chris Case 1:12:24

Yeah, I think we could do an entire podcast about exercise addiction. But that is a true condition that will affect your social life, your personal life, your professional life. And it’s a it’s a very serious thing. When you develop that and it’s um, it does, it does lead to those feelings of, of guilt you you ride not for the positive that it brings to you. But you ride to avoid the negative you exercise for the wrong reasons in that you’re you’re doing it to avoid feeling guilty about yourself. You’re you’re doing it to avoid the negative feelings you would have otherwise, so.

Trevor Connor 1:13:04

Okay, so you bring up a good point, I have no social life. My exercise is my career. Now. How did I pass this test? I

Chris Case 1:13:13

don’t know. I’m telling you, you’re a cheater, cheater. So the second million dollar question that we always get asked Leonard, when we’re giving a presentation on this subject is how much rest do I need? You know, the dosage is is one side of the coin. The rest is the other side of that same coin? If I’m training really hard, and you’re telling me Well, when you train hard, make sure you rest hard. What does that mean? And it’s another really hard answer to give people because it depends on a lot of factors in their life. I think one thing that I would point out is there’s different types of stress. There’s training stress, there’s life stress, which includes work and personal life. And maybe there’s been a death in your family, or you’re working on a big presentation. And you’re stressed about that. All of those things, or a divorce or a divorce or anything like that. Those are all to be taken into consideration when you’re talking about stress loads. And if you’re preparing yourself for the tour of the healer, and somebody dies, unfortunately dies in your in your life or you’ve got all of these other things going on, you really do have to take into consideration all the stress that that is burdening you with. I know that that’s a perhaps a vague answer. I think Trevor’s going to be able to give a little bit more specific answer about how to really tell how much rest you need or how much recovery you need. But that’s really something that can’t be stressed enough is the balance you have to strike between training, life and stress. And I know I know Leonard mentioned it earlier. You have to play up the fun factor. And try not to be too serious, especially if you’re a 55 year old living in Wichita, Kansas, racing in the 55. Plus category cross race with 15 of your best friends. guess there’s not too many people that care about how good you do. Sorry. Yep,

1:15:16

that’s right. Also, another thing that I’d mentioned is, as a Masters athlete, I still find that an awful lot of my training time is really rehabbing injuries. And that that in itself is another stress recovering from injury, also recovering from illness. And that it’s important to to factor that in when you figure out how much rest you need, that takes a lot for your body to to recover from an injury or from an illness. And to not underestimate that and think you can just bounce back and sit out two days and then

Trevor Connor 1:15:51

go for it again.

Chris Case 1:15:52

And that’s exactly what Ned over in told us when we did a podcast about aging and performance, he said the same exact thing, recovery, you have to pay more attention to the time you spend recovering, it’s not so much that your body takes longer, it’s that you feel like it takes longer to recover. It’s also you’re just more vulnerable to things. The older you are.

Trevor Connor 1:16:18

Yeah, I think that question of what is the right dosage of training, there isn’t a right answer to that. Something I like to say to my athletes a lot is if you’re sitting on a beach in Hawaii, you can train 20 hours and come back from that actually feeling pretty rested. If life stress is high, the weather’s bad, and kids are sick. And all these other things are factoring into your training and life five hours on the bike that week can kill you. So there is no, here’s the dose that’s going to fatigue you or here’s the dose you can handle it you have to factor as you said everything in. So I like to say to my athletes, there’s no such thing as overtraining, there’s only under recovery. And when you are figuring out how much recovery you need, you have to factor in everything in life and training. And your recovery needs to be commensurate to the stress that’s going on. And if that means that to keep it in balance, you can only train four hours a week and you want to train more than four hours a week. You don’t subtract from the recovery side of the equation, you figure out how to reduce the stress, other stresses so that you can do more training, there are tools that can help you with the recovery. Certainly resting heart rate is one just be careful with that because people get stressed about the resting heart rate and stress. pushes I just talked to an athlete two days ago, his resting heart rate was now up to 70. And he thought something was wrong like how much you stressing about your resting heart rate a lot. That’s why it’s high.

Chris Case 1:17:54

Yes, be careful of stressing yourself out about your resting heart rate.

Trevor Connor 1:17:59

But it is a good indicator. There’s a little test you can take online called the palms, p o m s, that can look at your mental state. I think that one’s really valuable because that’s going to factor in life

Chris Case 1:18:12

stress. Of course, the things that we’re talking about here really pertains specifically to performance and the recovery that’s going to provide for your best performances. Whether or not that’s going to ultimately prevent you from ever developing an arrhythmia is really hard for us to say. But it bears repeating that recovery is a good thing. There’s never overtraining just too much under recovery. Did I get that? Right, Trevor? Is that the one? Yeah,

Trevor Connor 1:18:41

I mean, there is such a thing as overtraining. But a good way to think of it is there’s no such thing as under overtraining, there’s just under recovery. Very good, very good. And I think you you led to another good take home, which is just because you ride your bike a lot doesn’t necessarily mean you’re living a healthy lifestyle. And I’ve seen a lot of very unhealthy cyclists. So again, if you are concerned about your heart and your overall health, you need to factor factor in everything, look at your diet, look at your sleep patterns, that’s going to help you recovery, too, is making sure the other sides of your life are healthy as well.

Chris Case 1:19:16

And there’s a lot more in this book, it must be repeated the haywire heart that goes into detail about some of those elements that we haven’t touched upon what is healthy, what isn’t caffeine, how does that affect the heart? how tall you are, how does that affect the heart and your your chances of developing an arrhythmia? Whether you’re male or female, all of these things. We couldn’t possibly cover all of the material. Interestingly enough, coincidentally, maybe not. There is a paperback edition of the haywire heart coming out in just a couple weeks, so please pick up a copy and check it out and let us know if you have further questions. Leonard and I are always here. Our third co author dr. john manarola. An electrophysiologist from Louisville, Kentucky himself. Have a bike racer is also a wealth of knowledge. He has a a website, dr. john m.org. I believe it is and there’s so much more information there. Thanks for listening. That was another episode of Fast Talk. I hope you were as fascinated as we were to take a deep dive into heart arrhythmias. As always, we love your feedback. Email us at Webb letters at competitor group.com Subscribe to Fast Talk on iTunes, Stitcher, SoundCloud and Google Play. And please we’re making a call for people to go onto iTunes specifically and give us a good rating. If Of course you like what you hear. The ratings mean a lot to search engines in finding Fast Talk for others. If you love our Fast Talk podcast, please share it with others. Be sure to leave us a rating and a comment wherever you can. While you’re there, check out our sister podcast the velonews podcast which covers news about the weakened cycling. Become a fan of Fast Talk on facebook@facebook.com slash velonews and on twitter@twitter.com slash vile news, Fast Talk is a joint production between velonews and Connor coaching. The thoughts and opinions expressed on Fast Talk are those of the individual for myself, Chris case for Trevor Connor, Coach Connor and for Leonard Xin. Thank you for joining us and thanks for listening.