Not every coach has what it takes to work with younger athletes. You can be an expert in the sport and fail miserably if you don’t know how to engage effectively with kids. This module of Joe Friel’s Craft of Coaching profiles one of the nation’s largest junior cycling clubs, with some practical guidelines on what works best. From grass roots to the World Tour and the Olympic Games, we also get a closer look at the individual development programs of two prominent junior athletes who made that elusive but highly rewarding transition from promising youngsters to world-class contenders.

How to Develop Younger Athletes

Prioritizing Long-Term Athlete Development

The Long-Term Athlete Development (LTAD) Program maps the priorities of coaching juniors in order to promote the successful graduation to lifelong athletes. Largely popularized by Canada’s Sport for Life over a decade ago, this program continues to be the gold standard even as more research rolls in on youth sports.

First comes fun, then a steady progression to training and performance. Prior to age 12, coaches of juniors should focus on helping the athlete complete the first three steps, in sequence. Steps four, five, and six take into account that kids develop at different speeds, so this second progression is led by the athlete under the patient guidance of a coach.

Podium finishes early in a young athlete’s career are usually the result of early development, a growth spurt, or more time in the sport translating to more skill acquisition. Even an athlete with an early birthday can have an advantage in their category. Access to the sport, both in terms of opportunity and equipment, also factor in. However, research has shown that these differences even out over time.

In part, this is why the Positive Coaching Alliance directs coaches to embrace two goals in working with juniors:

- Teach life lessons through sports.

- Strive to win or achieve a personal best.

When athletes understand the day-to-day behaviors that will help them succeed—things like being prepared, learning how to communicate with a coach and teammates, setting a goal and consistently following a plan—they get more enjoyment from the sport (and often performance follows).

Working with parents of kids and juniors

For better or worse, parents play an influential role in the performance of their kids. Even at a young age, enthusiasm can teeter into expectations and pressure, causing undue stress on young athletes. Coaches can get it all right and struggle to retain juniors, which is a loss for everyone involved—the athlete, the team, and even the sport.

For more on this topic: Julie Young discusses how she helps juniors develop mental toughness.

Find out how Boulder Junior Cycling partners with the parents of juniors to create a healthy team culture and membership. There are valuable lessons to be learned for clubs large and small.

How to Coach Parents of Young Athletes

Case studies in coaching juniors to world-class performance

In establishing a junior development program for Norway’s Triathlon Federation, Coach Arild Tveiten effectively threw down the gauntlet on the international stage, producing a team of Olympians that took the sport (and the world of Ironman) by storm. He’ll be the first to tell you that it’s not talent, but a steadfast and serious commitment to training that brought his young triathletes tremendous success.

The Making of a Triathlon World Champion

Dr. Iñigo San Millán has compiled 27 years of data on cyclists, with a particular eye toward the metrics and characteristics that make athletes successful in the professional peloton. When he was asked to coach Juan Ayuso in preparation to join UAE Team Emirates, many of those components were already in place. Hear more from Dr. San Millán on how Ayuso was able to collect some Vuelta stage wins early in his pro career.

Dr. Iñigo San Millán Special: Developing Young Talent in the Pro Peloton

Developing the aerobic capacity of junior athletes

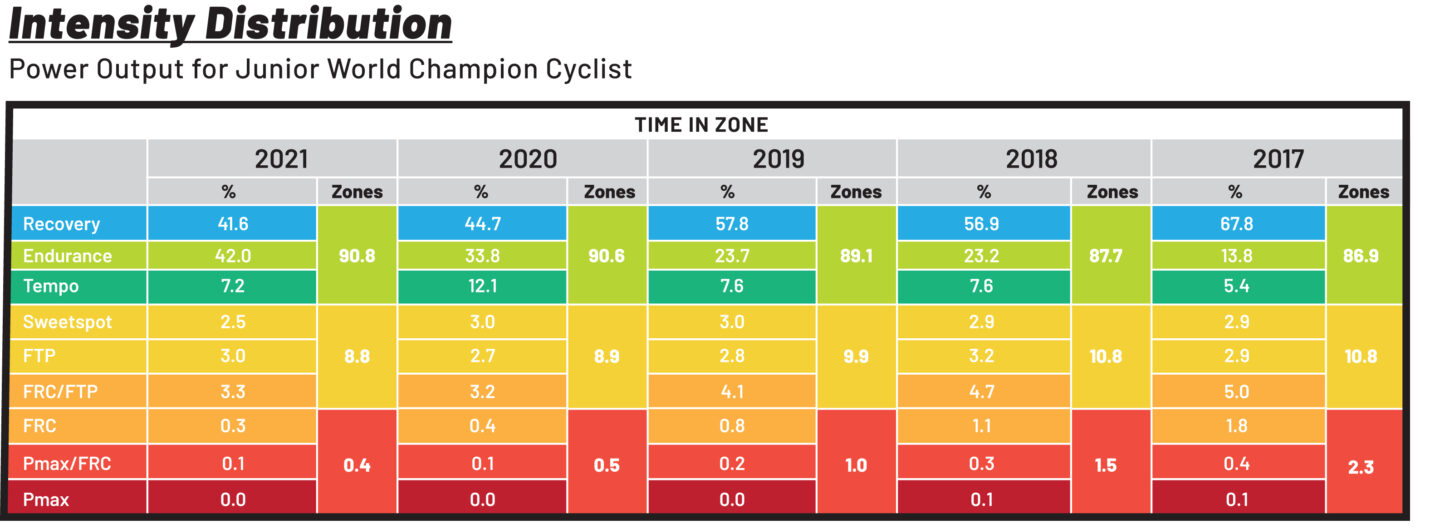

Both Tveiten and Dr. San Millán explained the importance of fully developing a young athlete’s aerobic base in order to realize their full potential. It’s an effort that requires consistent, disciplined work season over season. To achieve this goal, these coaches lean toward a more polarized training method. Many coaches use those hard anaerobic efforts to get short-term gains and podium finishes for their athletes, but it doesn’t pay off later in an athlete’s career.

Read more about polarized training and explore the case studies from Dr. Stephen Seiler, including data from a young up-and-coming junior cyclist, Norwegian Per Strand Hagenes in the first few years of his career to illustrate the rewards of a longer view on athlete development and performance.

Disciplined work below aerobic threshold is not always practical with younger athletes. Webber stresses that most kids just want to race their bikes and have fun—you can’t tell them not to go hard. “We talk about zones and educate them, give them a heart rate monitor, and explain what happens in Zone 2. But implementing these ideas and tools more consistently comes later.”

What science says about athlete selection

Some common themes emerged from our conversations with Pete Webber, Arild Tveiten, and Dr. Iñigo San Millán, both for young athletes building up to a world-class performance or those competing locally. What follows is an overview of the latest research to better inform your coaching practice and just enough detail to help you know which studies you might want to read for yourself.

What Makes a Successful Junior Athlete? The Research Might Surprise You

What follows is a summary of the research on how relevant experience, performance, specialization, and physiological metrics are for junior athletes. As explored in the previous article, these studies make the case that with tweens and early- to mid-teens, coaches are better off looking past the podium—and maybe even beyond the sport.