Over my coaching career, I have been fortunate to work with a number of Olympians and world champions, first in cycling and then in a wide range of sports. I say this with a great deal of humility because coaches get credit for someone else’s accomplishment—the athlete does all the work to make it happen. That said, what follows is my method for mapping a season of training. I used this same approach with great success across cycling disciplines, including road, mountain bike, and gravel. There are specifics to be addressed for each discipline or sport, but those mostly come into play when the athlete is mature in the sport and competing at higher levels of competition.

Most athletes do not have unlimited time to train. Consequently, when I begin training cyclists, I’m not focused on improving one component of riding, such as sprinting or climbing. Instead, I focus the training on raising the athlete’s overall fitness level. With hard training on a day-to-day and year-to-year basis, it’s my belief that athletes can accumulate a high volume of intensity that will prepare them for racing at the highest level of the sport. I also believe that no matter how competent a cyclist is at climbing, they can climb better with a higher level of fitness and conditioning. The finite details of improved sprinting or climbing need to come after conditioning is mostly developed over years of training.

In working with road cyclists (as well as mountain bikers and masters athletes), the primary preparation phase typically runs from December through March to get the athlete ready for the slate of spring races. A secondary prep phase from May through July leads up to mid- to late-summer racing. By that point, the athlete can race as late into the season as their form/fitness allows. Naturally, any plan for a season of training must accommodate many contingencies. There isn’t an obvious path, and plenty of decisions need to be made along the way.

Key Principles of Block Training

- Use consecutive interval sessions to create an overload in a targeted energy system.

- Block maximizes the volume of intensity and recovery over time.

Rules of Progression and Overload

- Use consecutive sessions to enhance adaptation.

- Work at intensity until power drop-off is dramatic (>40%).

- When intensity cannot be maintained, stop the workout and start recovery days.

- When in a racing phase, reduce overload and transition to 2-week blocks.

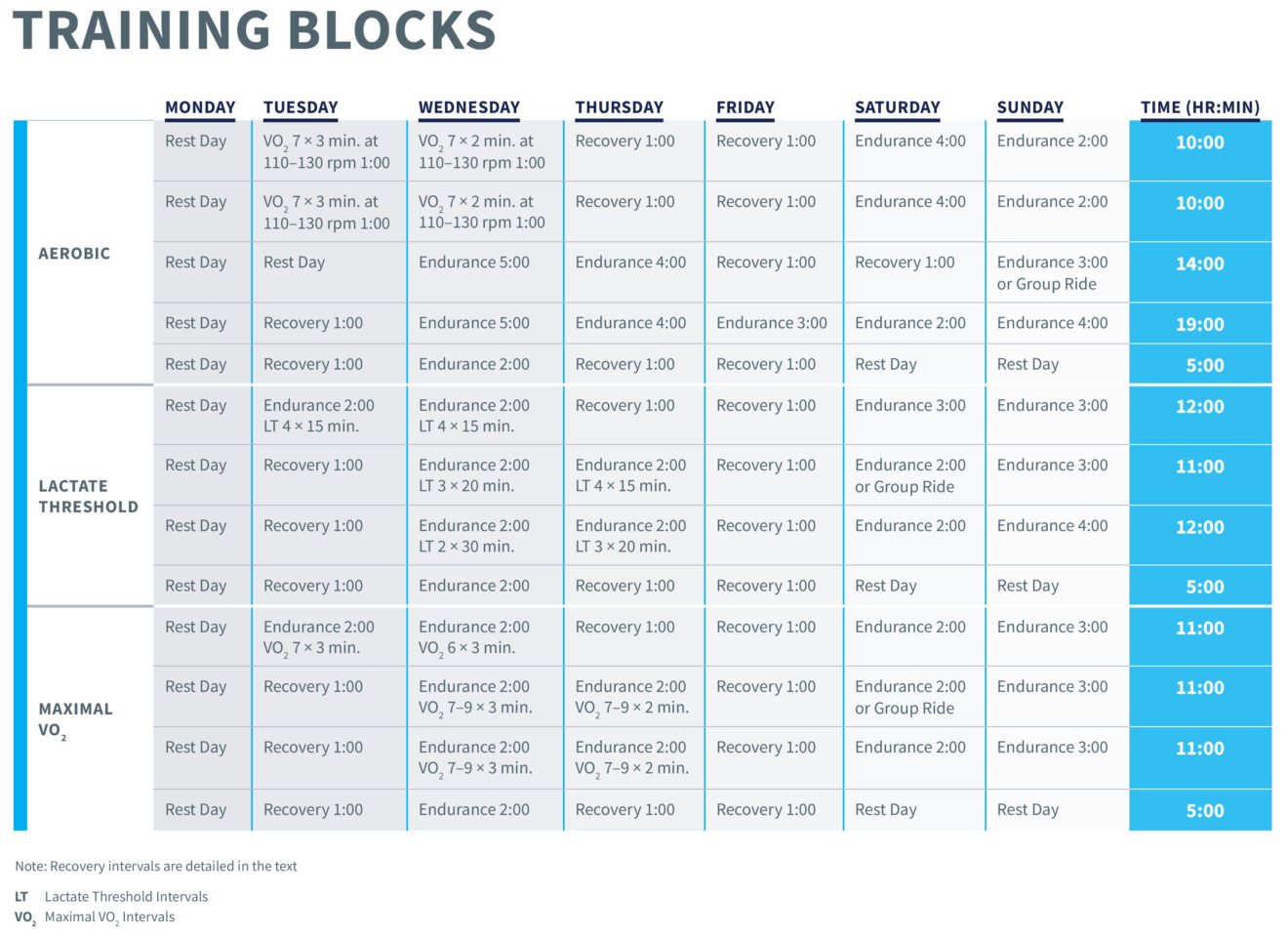

Block training targets a specific energy system to create overload with consecutive interval sessions. I use three blocks: endurance, lactate threshold, and maximal VO2. Each block is followed by one week of active recovery before progressing to the next focus. Here is how it would break down for the primary preparation phase for a road cyclist—from December through March.

Block 1: Endurance

There are a few goals we are looking to achieve in the first month of training:

- Increase aerobic fitness without stressing the muscular system.

- Increase endurance with high-quality training.

We typically start with intervals in the first two weeks of December. If a rider is starting the season aerobically fit because they have been training consistently for years, there isn’t a need for the endurance training (i.e., long slow distance) that an amateur athlete would be doing at this time.

In these initial two weeks of December, we focus on max VO2 intervals at a high cadence. We want to shock the system, so these are either back-to-back sessions scheduled over two days or doubled up on the same day with morning and afternoon sessions over two days.

Max VO2 high-cadence intervals

| 7 × 3-4 min. at 110–130 rpm | 3 min. recovery |

The focus is on cadence, not power, in these sessions. The work interval is at the maximal power that the athlete can hold while keeping cadence high, not the athlete’s max VO2 power.

For the sessions that follow, either the interval is shortened or the rest is increased. Endurance or group rides are done on the weekend. The concept is to increase aerobic fitness and the potential for adaptation so that in the endurance block that follows, the athlete can complete the miles at a higher speed or power than they would have without this block. The max VO2 intervals get cyclists aerobically fit in a short period of time. Meanwhile, the high-cadence work at lower power prevents residual fatigue.

After these initial two weeks, we begin two weeks of endurance training, doing two or three consecutive days of long rides (4–6 hours), followed by a recovery period lasting two or three days. The endurance work effectively creates a valley of fatigue in the second and third days. After two weeks, the athlete will recover for a week with easy rides lasting 1–2 hours.

It’s interesting to note that had the athlete started here, they might be riding 18 mph for 4 hours. After doing the interval work, it’s more likely that they are riding 19 or 20 mph just a few weeks into the season. As a result, they will get more benefit out of these endurance rides—more quality from the same training.

The addition of these four max VO2 sessions make all the difference in this first block of training. I’ve found that athletes just ride faster when it comes time for the endurance rides.

Block 2: Lactate Threshold

By the second week of January we are ready to do lactate threshold (LT) training. The training in this block is structured similar to the previous block. We do Tues./Wed. or Tues./Wed./Thurs. blocks with an endurance or group ride on the weekend.

Throughout this block we progress the work over the 3-week block. LT consists of four 15-minute efforts with 10 minutes recovery, again on consecutive days. The goal is to get in at least an hour at LT. The next day the length of the interval is decreased to maintain the same intensity, but the total time at LT remains the same. On the weekend, training can be group rides or endurance.

| WEEK 1 | WEEK 2 | WEEK 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAY 1 | 4 × 15 min., 10 min. recovery | 3 × 20 min., 10 min. recovery | 2 × 30 min., 10 min. recovery |

| DAY 2 | 4 × 15 min., 10 min. recovery | 4 × 15 min., 10 min. recovery | 3 × 20 min., 10 min. recovery |

For elite males, another interval can be added to each of the sessions, making time at LT closer to 90 minutes in the Week 2 and 3 blocks.

My approach to lactate threshold training

It is my belief that you don’t have to train at or above an individual’s lactate threshold to gain results. I believe you can train a little below it. Even if you’re too conservative and train well below it, you can add time or another interval to get the necessary work benefit. In my experience, the adaptation comes in the volume of time the athlete spends near LT, not the intensity.

At the end of a session of lactate threshold intervals riders are typically very tired. In my opinion, this indicates they went too hard. If we were to approach the session more conservatively, the riders would ride the intervals at least 10W lower than where they think they should be or have been tested at in regards to lactate threshold. So if the rider’s threshold is 255W, we start these intervals at 240W. If the rider isn’t challenged, as the interval block progresses I will first change the prescription to add more time, before increasing intensity (a higher power output, e.g., 245W). In simple terms, this increases the effectiveness of the adaptation by increasing volume. It’s easier to train athletes this way because, as a coach, you can’t make a mistake. In this example, the overall goal is to get 6 hours of training at 240W, which is better than doing a couple of hours at 255W, a couple at 245W, and a two hours at 230W with much more residual fatigue.

Avoid the mistake of middle training

Many people think that LT is where riders time trial—the hardest effort a rider can sustain. Elite athletes can ride above threshold for a long time, sometimes close to an hour. In reality, riders generally train at a power output that is between their lactate threshold and maximal VO2. Consequently, they are not working either system. They are not going as hard as they can for the short period of time exploiting their muscular power, nor are they going as long as they can without causing that spike in lactate. I call this “middle” training—training to tolerate lactate and not training to limit its production. Accumulating training volume near LT gives riders the same adaptation to lactate as training over or at LT.

Moreover, it’s been my observation that when cyclists train over LT, there is an increased potential for problems. It’s more difficult for the riders to complete LT training on the second day or put in quality endurance rides later in the week. Instead, they are stale and fatigued. It’s time to recover, and adaptation was likely compromised in the process.

Advice for coaches

Training below LT results in fewer coaching mistakes. It’s dangerous to do consecutive intervals at this intensity. Coaches (and athletes) get insecure about whether the LT work will be enough and they compensate by increasing the intensity.

Here’s a safer approach: If the athlete feels you haven’t prescribed enough work, I suggest you just add intervals. This way the athlete still has adequate resources for recovery and endurance rides. You could prescribe up to two hours a week for three straight weeks, plus quality endurance work on the weekends. The athlete will come out of the block fatigued but not overly tired.

Block 3: Maximal VO2max

In this block we start group rides and hard climbing on weekends. Then we move on to specific intervals. This can be shortened to be a two-week block if the race calendar is about to start. During the week we do short intervals to build up power and fatigue tolerance. These are maximum efforts, similar to what we use in racing. The work interval is shorter on the second day, keeping a one-to-one work-to rest ratio.

Maximal VO2 intervals

| DAY 1 | 7-9 × 3 min. | 3 min. recovery |

| DAY 2 | 7-9 × 2 min. | 2 min. recovery |

On these intervals, the athlete will go out as hard as possible with the goal of getting through the interval. This is not the same as riding at the highest average power. If the rider has put in a really hard effort, they are basically at LT power by the end of the last interval in the set. By that point, they know it’s time to stop the intervals.

Max VO2 intervals can also be incorporated in a long ride (2-3 hours). This is specific to racing (i.e., hard efforts that a rider needs to match late in the race), but intervals done in this way will not improve the rider’s power output because of the fatigue created by the longer ride. We must weigh when to add in these sessions. It’s a decision of whether to prepare for racing or to improve a quality that is specific to racing, power development. In coaching, I generally defer to improving the athlete’s physiology rather than focusing on the specifics of racing. As always, at the end of the block is one week of rest.

Racing Season

The first three training blocks take us to March when the racing season starts. Whether the goal is to win races or just train for the season, we take the same approach, bringing together all of the systems that the athlete has been developing in preseason. This is racing: We combine the endurance of December, with LT training, with the race-specific VO2max intervals done at the end of February. Now we are pulling all of the physiological systems together. The body might need a week or two of racing to adjust to the demands of working in the middle ground, but after that the athlete is ready to go. In preparing cyclists for Redlands, we would plan a week of racing to complete the preparation. Group rides can also be used to accommodate the adjustment.

Manage fatigue with recovery

Racing creates new challenges. During the first three blocks it’s easy to identify fatigue because we are working on one specific energy system at a time. But in racing, we integrate all of them, so it is more difficult to determine the nature of the fatigue. Is the rider tired because they raced too hard? Did they come into the race tired? Thanks to the recovery week prior to the start of each block, I know riders will come into the next block fresh and ready to train that specific energy system. In the race season, it’s not so clear-cut, so the focus is on racing and recovering.

Don’t shy away from racing hard

Cyclists will tell me, “I’m going to save it until the big races in the middle of June or July.” In my opinion, this is a misconception. In fact, an athlete’s primary goal may be in June or July, but we must train as if our primary goal is in March. This is the only way to get better.

Whether we are looking at a full year or taking a longer view of 2–4 years, what is the limiting factor? We know that intermediate cyclists could do all of the same the training as the elites, but their performance will not measure up. Why is this? They can’t accumulate the same volume of intensity throughout the year. If elite riders are racing regularly, they get the benefit of adaptation that comes from being at the front and racing hard throughout every race, year after year. The riders who are saving their top racing form for July are more likely to be dropped because they are not getting this additional volume of intensity in their season. It’s a gap that is further widened year over year.

Aim for volume of intensity

Over the course of a year, the group that follows the block program is likely to accumulate 20 percent more intensity. And what surprises many coaches is that the volume of intensity should be the same for all riders, elite and nonelite. Naturally, the power generated by non-elite athletes will not come close to what the elites can do. Less experienced riders haven’t had the time to adapt to it. A misconception is that less experienced or capable cyclists should do fewer intervals (e.g., 5 instead of 7 sets of max VO2 intervals). This prevents the cyclist from achieving a general volume of intensity early in their racing career. As soon as racing season starts, the cyclist will be behind and they will never catch up to those athletes who are surpassing them in the volume of intensity completed throughout the year.

When is the rider going to do the work? Increasing intensity even 10 percent in a year is significant. If the rider isn’t starting the race season in top condition, I’m doubtful enough work can be completed to raise the overall volume of intensity throughout the year to continue progressing.

Modify recovery, not work

If the race-specific intervals in the maximal VO2 block are truly too much for beginning riders, keep the intervals the same in order to accumulate the time at intensity, but extend the recovery time. Keep the work to just two days, never a third day. After the two days make sure the rider has two or three days of rest. The benefits of these intervals can’t be realized if the rider is not recovered. The goal is to get the athlete overloaded day after day, without accumulating fatigue week over week. Elite athletes can recover faster, increasing their capacity for work.

Race Preparation

There is a specific protocol that I use in the lead-up to any race.

If the race is on Saturday, we do a 4-hour endurance ride on Wednesday. Then, a few conservative LT intervals on Thursday, generally around 10 minutes in length with 5 minutes recovery. Friday is an easy ride with 2-minute efforts that effectively “ramp” to maximal power by the end of the interval. So if a rider’s max 2-minute power is 300W, for these intervals, they may start at 200W and only get to 300W for the last 10 seconds of the effort. In other words, the rider finishes the interval at all-out intensity. The recovery can be 2-4 minutes.

Protocol leading up to a Saturday race

| Wednesday | Endurance ride, 4 hours |

| Thursday | Ride with 2–3 × 10 min. LT intervals, with 5 min. recovery |

| Friday | 1–2 hours, easy ride with 3 × 2 min. ramping efforts, with 2–4 min. recovery |

| Saturday | RACE |

Note: I don’t see a need for the cyclist to ride every day. Whether a 1-hour recovery ride or a day off the bike, it’s the athlete’s preference.

Following a stage race riders know they will be tired so they are more inclined to fully recover before doing anything else. It’s harder for regional or Cat II riders to know what to do during the week. They race hard from weekend to weekend. Yet, on Tuesday and Wednesday, they might do some intense training. At the end of four weeks they wonder why they aren’t feeling good. This is another example of “middle” training. By doing a little bit of everything, these riders never get good at anything.

After racing Saturday and Sunday riders would benefit more from doing a long ride on Monday, working endurance. It is not good to do intensity when feeling fatigued in the middle of the season. An endurance session complements the weekend of hard racing, effectively creating a block of three days of competition and training. Recovery follows on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. By the weekend, the rider is ready to race again. During the months of May, June and July build in one week of recovery every month.

In June and July the rider will peak and taper for big events. Recovery from race to race is critical in order to be able to fit in as many stage races as possible. Prior to a big race we do a 10- to 14-day taper.

Recovery protocol leading up to a 2-day stage race

| Monday | Endurance ride |

| Tuesday | Recover |

| Wednesday/Thursday | Short, intense group rides |

| Friday/Saturday | Recover |

| Sunday | Race |

| Monday/Tuesday | Recover |

| Wednesday | Long, easy ride |

| Thursday | 1.5 hr. ride with 8 min. LT efforts |

| Friday | Recover |

| Saturday/Sunday | Race |

Note: The point of this block is to maintain race readiness, not to train between races.

Most of the top racers compete into September or October. However, before embarking on the last three months of the season, I want riders to take a minimum of 10 days off in the August timeframe—five days off the bike, followed by five easy days on the bike. From there, the riders can finish the season by repeating the race block they just completed.

An average rider might finish the season by September and will take it easy for a couple of months. But, compared to their elite counterparts, they will have lost three weeks of intensity in those eight weeks that they won’t be able to make up.

My advice to athletes is simple: Race as long as you can. By structuring the races as I’ve described, the cyclist shouldn’t be totally fatigued come October. Find races at the end of the season that allow for adequate training, followed by a 10- to 14-day taper. This helps the athlete finish the season in excellent condition, not overly fatigued for the start of the next season.

Author’s Note: This block training program is born out of research conducted on overload in 1994, led by David T. Martin of the University of Wyoming in conjunction with the U.S. Olympic Training Center. I was a postgraduate student of Dr. Martin’s program at the time of the study. I further refined my training block method over years of preparing cyclists to compete at the highest levels of the sport as a physiologist for the U.S. cycling team.