Athletes and coaches alike can make the mistake of becoming overly focused on data. This is a problem because technology does not allow us to quantify the actual (internal and external) physiological stress of training with sufficient validity. Consequently, as coaches we cannot base our training prescription solely on things we measure such as power, pace, or heart rate. There are countless examples of this. It is very difficult to quantify the load of running up a mountain trail—in particular, the power measurement is usually invalid because the metrics and software algorithms cannot account for the complexity of the environment. But the fact we can’t measure something doesn’t mean it is inconsequential—as you’ll learn with the biopsychosocial approach. Data can present illusions and fail to reflect the true demands of the training session.

When coaches are too focused on the physical side of training, they are likely to miss important psychosocial information that directly impacts performance. For example, coaches can propagate a reductionist view when they overemphasize Chronic Training Load (CTL) as a target for training or quantify the amount of energy used in a session in terms of calories, or energy in and energy out. This can, in turn, trigger in the athlete unhealthy perfectionist tendencies, disordered eating, and a whole lot of other sporting nasties.

The discipline to complete workouts and eat appropriately are important to success, but such a focus can become unhelpful if the athlete or the coach fixates on it. Ultimately, it can even lead to a maladaptive and dangerous response such as overtraining, injury, or eating disorders. The consequences are rarely immediate, as long-term health implications can take years to become obvious. Thus, it’s easy for coaches not to recognize or be accountable for the way they prescribe training. Working with a biopsychosocial model can help prevent this.

RELATED: What Is a Biopsychosocial Approach to Coaching?

The biopsychosocial approach can more accurately capture the stress of training

A biospsychosocial perspective makes it possible for a coach to better assess the full extent of the stress in their athlete’s training. Being able to articulate stress is an invaluable skill that looms large in the coach-athlete relationship, for both coach and athlete. Heart rate variability (HRV) has risen to most-favored data status in recent years, as this physical metric indicates levels of fatigue. But sometimes it’s better just to ask the question: How are you?

From there, the HRV value may help us ask more searching questions. For example, an athlete may say they feel fine, but their HRV value suggests they need a week in bed. Therefore, the coach needs to ask: How honest is the athlete inclined to be with me? The answer to this question will affect how training is prescribed.

Note that athletes are not always honest with their coaches because they do not want to appear weak or may fear de-selection. Whether an athlete is choosing not to be fully honest with their coach or out of touch with their own body, it’s up the coach to make sense of the situation and that requires a biopsychosocial perspective.

HRV has risen to most-favored data status in recent years, as this physical metric indicates levels of fatigue. But sometimes it’s better just to ask the question: How are you?

Andy Kirkland, Phd

We can accomplish more in community

At the heart of biopsychosocial coaching is a different conceptualization of self. In Michael Crawley’s book, Out of Thin Air, and from my experiences in Kenya, the concept of being an individual and having control of one’s own destiny has far less prominence than in some Western cultures. It’s not “I am an individual,” but “we are a community.”

We are better off together, working as a group to achieve our goals. It’s natural to want to achieve as an individual, but we need each other to get there. I liken it to professional road racing in cycling in multi-stage races. The strongest rider will only win if their team works effectively together. Attempting to go it alone usually means being spat out the back of the peloton. The best team leaders will recognize the importance of what success looks like to their teammates too and will give others the opportunity to lead if they’re having a bad race.

In underprivileged communities, where many East African runners come from, access to proper education and medical services is limited. Life challenges are great, this influences the individual’s beliefs surrounding achievement and what is possible in life. If you come from a village where there have been multiple runners who have won on the world stage, then repeating such feats may seem possible. The rewards of success mean that runners can give back to their families and the wider community. Indeed, it is expected. It would be misguided to suggest that individual athletes aren’t driven to succeed. Rather, their individual beliefs and behaviors around sport have been shaped by their social environment.

We can’t succeed until we believe

A 1987 study by Brehm and Self explored the mobilization of effort and concluded that we only put effort into what we believe we can succeed at doing. As coaches, we need to help athletes develop and push each other to shape these beliefs. The advantages of doing so can be seen in communities throughout the world where there have been deep concentrations of talent. This is what Rasmus Ankersen calls a “gold mine effect.” Without that high level of competition pushing everyone in the environment, those elite performers would not be able to achieve the same level.

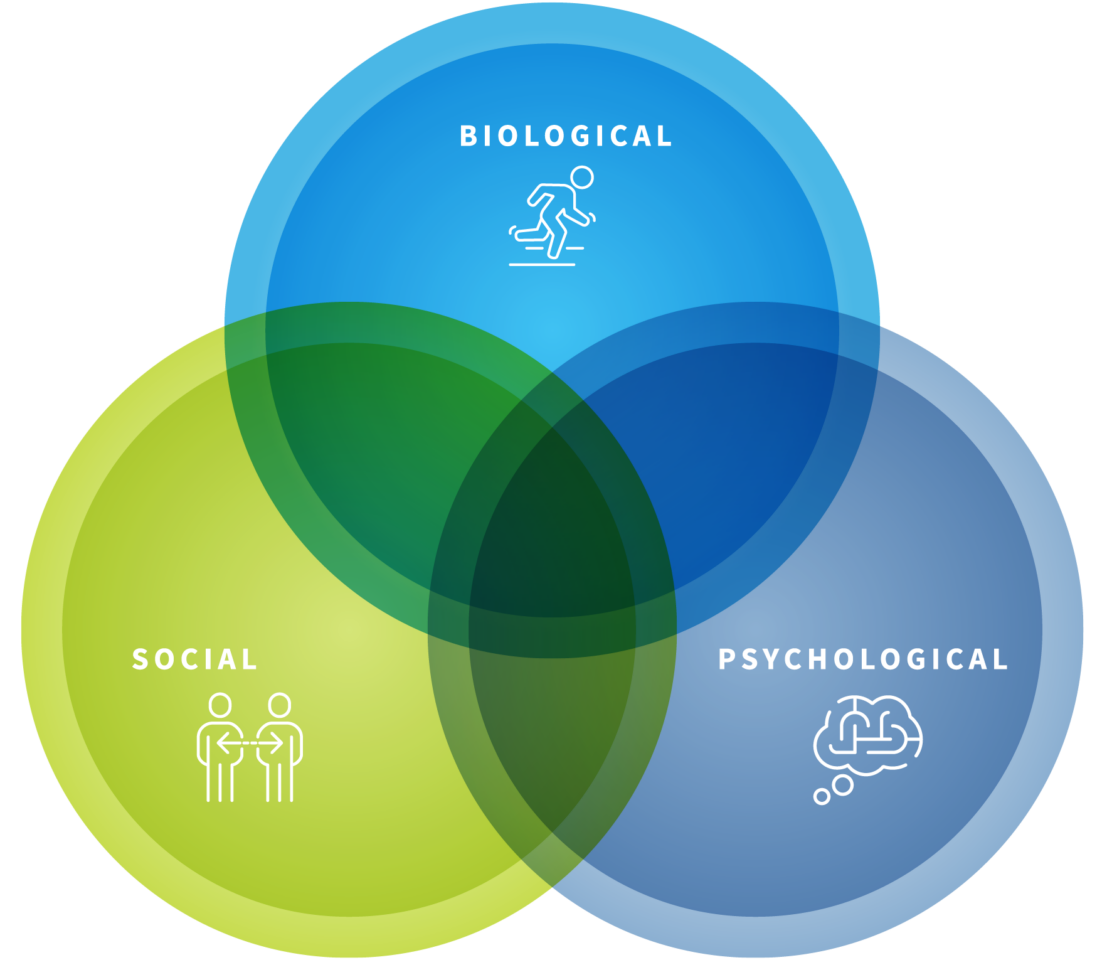

There are multiple examples of this effect throughout the world, including certain parts of Scotland known to produce great mountain bikers, Norway’s recent line-up of successful triathletes, Iten, Kenya’s running culture, and Boulder’s reputation as a hub for endurance sport in Colorado. These places exist because of complex biological, psychological, and social elements that cultivate the athlete’s belief that success is possible. Similarly, when Roger Bannister broke the four-minute mile barrier, which had previously been thought to be impossible, many other athletes in the U.K. followed suit.

The talent pool didn’t magically increase, but belief changes the moment you know that someone else has done it. If that person has come from where you live, then the belief effect can be contagious. While the gold mine effect has played out at the highest levels of sport, the power of community can also be seen when people pursue their sport and fitness goals within a larger community.

We can mobilize effort through community

Parkrun, a global phenomenon that Chrissie Wellington is associated with, has become one of the most successful physical activity interventions to motivate people to be more physically active on a global scale. The secret to parkrun’s success is not that it started with a masterplan. Rather, success developed as the parkrun community grew. There was a place for everyone, including the volunteer helping with timing, the elite runner who wanted a fast 5K race, the young couple where one is pushing a pram and the other is going for a PR, and an old-aged retiree chatting to the tail runner all the way round.

They may all have different goals and view success very differently. But none would reach their goal without the help of others. There’s scientific evidence to suggest that parkrun is so successful because it offers a biopsychosocial environment that is completely free to runners.

I have prescribed parkrun to pro athletes because it gives them an opportunity to run with others. I want them to get to the park and run with the grannies. Of course, they are going to line up with the group at the front that they can compete against. Lucy Charles-Barclay has done several of these events—you never know who is going to show up.

The biopsychosocial approach to performance development is an orientation and way of thinking rather than a specific training method. There are some ecological models of coaching which capture its essence in which people, task, and environment are fundamental to their application. From my perspective, there is no ideal or perfect way to coach. Rather, we need to be agile in our approaches, not holding on to particular methods of prescription such as an 80:20 method or some fancy periodization. Rather, we should think of performance and training in terms of the complex interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors.