We explore the training, pacing, sleep strategies, and psychology of ultra-cycling events.

We explore the training, pacing, sleep strategies, and psychology of ultra-cycling events.

We explore the training, pacing, sleep strategies, and psychology of ultra-cycling events.

We explore the training, pacing, sleep strategies, and psychology of ultra-cycling events.

We explore how to effectively and efficiently train for ultra-endurance events on limited time.

For years we have been told to load up on carbs prior to an event, yet eat very little during competition. Recent research has shown that athletes can ingest more carbohydrate during training and competitions than previously thought.

The challenge of consuming calories on the go, day after day is one of the most difficult to overcome. We spoke with several ultra-cycling veterans to learn their strategies.

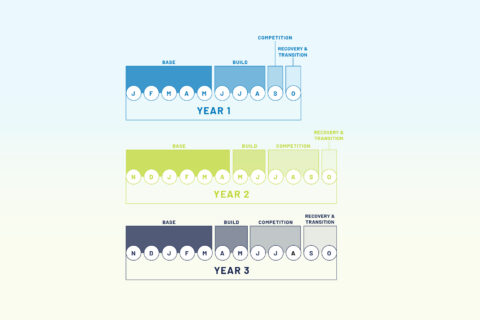

If you’re looking to tackle some ultra-endurance events it’s important to take a longer-term approach to your training that extends beyond a single season. We explain how and why.