You might never sprint during an Ironman or ultra-running race, but that doesn’t mean you can’t benefit from some HIT.

You might never sprint during an Ironman or ultra-running race, but that doesn’t mean you can’t benefit from some HIT.

You might never sprint during an Ironman or ultra-running race, but that doesn’t mean you can’t benefit from some HIT.

You might never sprint during an Ironman or ultra-running race, but that doesn’t mean you can’t benefit from some HIT.

In part 3 of our series on movement literacy for cyclists, Dr. Stacey Brickson delves into stability and strength to make you a healthier cyclist.

In this multi-part series, Dr. Stacey Brickson details several tools built on a hierarchy of mobility, flexibility, stability, and strength, designed to make you a healthier cyclist.

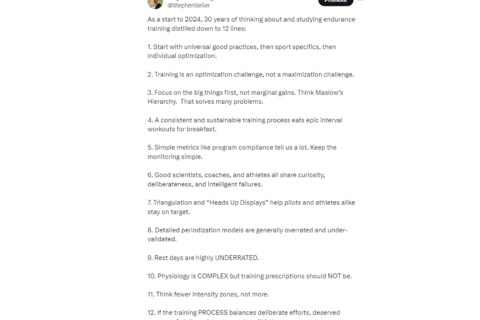

After 30 years of studying exercise endurance training, Dr. Seiler distills it all into 12 fundamental practices.

Lately, the Norwegian method for endurance training has the world abuzz. In reality, its core tenets have been around for decades.