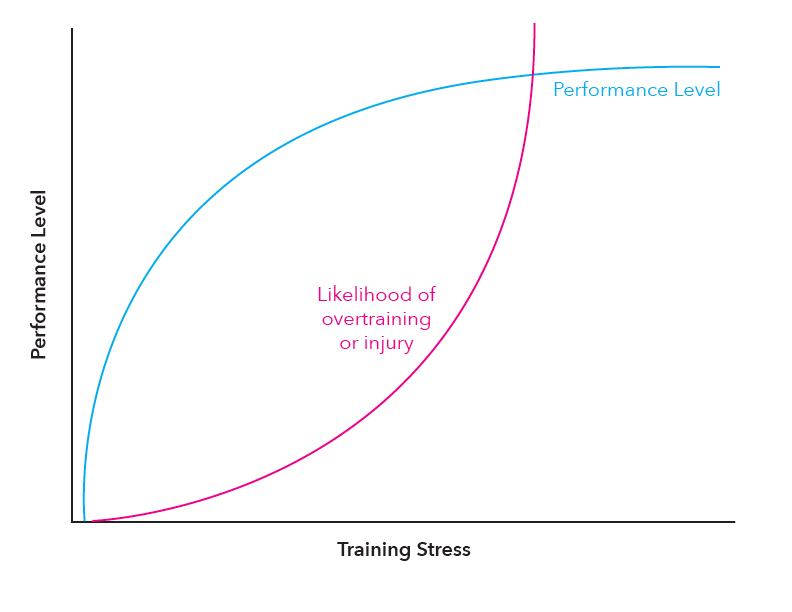

Eighty percent of what you need to know about endurance training can be illustrated by a simple graph. Coach Connor and his mentor Glenn Swan explore this simple concept.

Eighty percent of what you need to know about endurance training can be illustrated by a simple graph. Coach Connor and his mentor Glenn Swan explore this simple concept.