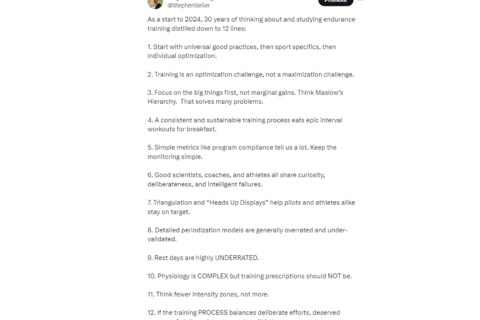

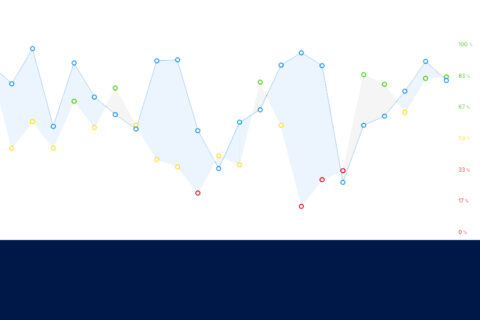

Crunching numbers is one thing, but if you want to turn data into victory, here are a few key things you should do and a few things to avoid.

Crunching numbers is one thing, but if you want to turn data into victory, here are a few key things you should do and a few things to avoid.